Part of the Series

The Road to Abolition

Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

The case against the United States prison system is overwhelming. Numerous studies have revealed inexhaustibly that prisons do not provide public safety by decreasing recidivism but instead fuel racial and economic injustice, place enormous strain on communities impacted by incarceration, undermine real accountability for harm and inflict further trauma.

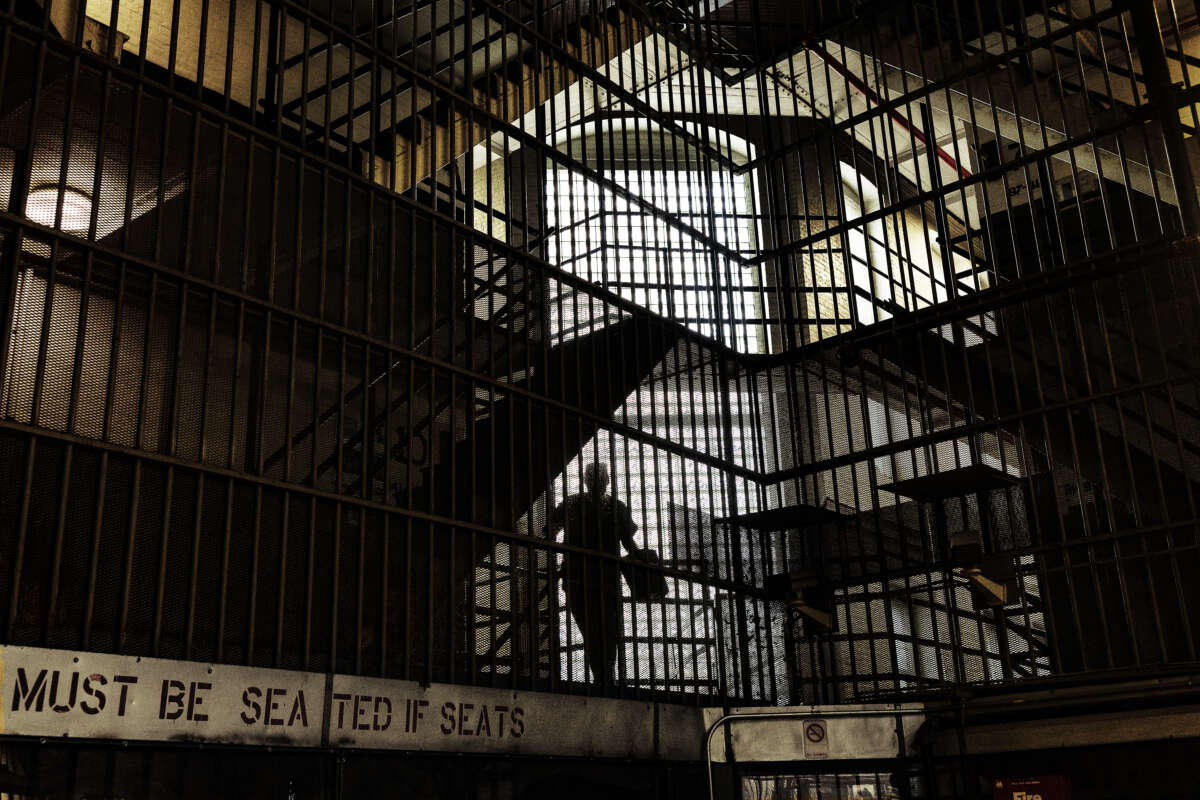

Carceral environments are detrimental to health care, counseling and treatment for addiction. Seen in this light, prisons are not places of rehabilitation but sites of punishment and inequality that threaten basic rights and liberties in a democratic society. No amount of effort to redesign prisons can make them viable instruments of justice. The pressing question is no longer how to reform the prison system but how to begin to move beyond it.

In Massachusetts, state legislators are debating a simple but elegant way forward: Stop building more prisons. The bill in question, a five-year moratorium on new prison and jail construction, would help propel efforts to further reduce the number of people in prison and serve as a model for other states as they seek to repair the damage inflicted by mass incarceration. On June 21, the Joint Committee on State Administration and Regulatory Oversight reported favorably on the prison construction moratorium bill, sending it to the Senate Committee on Ways and Means. The bill must now find its way to the floor before the legislative session concludes on July 31.

This is not the prison moratorium’s first time under consideration. In the previous legislative session, the moratorium passed in the State House before being vetoed by former Gov. Charlie Baker. It has now returned at an important moment. The moratorium would halt plans for a new $50 million women’s prison intended to replace an existing facility at MCI-Framingham. Curiously, the proposal for this new prison comes at a time when the number of incarcerated women at MCI-Framingham has decreased from over 600 in 2012 to approximately 200 in 2023.

The new prison is being billed as a “trauma-informed design,” an approach to prison architecture claiming open spaces and natural daylight can make incarceration a rehabilitative experience. The promotional material of HDR Inc., the architecture firm involved, speaks of “biophilic design principles” and features images of gleaming new facilities adorned with abundant windows and cool, soothing colors. Architects opposing prison construction question the validity of claims about this new ideology of prison design. Likewise, the National Council for Incarcerated and Formerly Incarcerated Women and Girls along with Families for Justice as Healing, abolitionist organizations leading the charge for Massachusetts’s prison moratorium, contend that “trauma-informed design” does not overcome the fundamentally traumatic nature of incarceration. Instead, trauma-informed design appears to be a new iteration of what former prisoner, abolitionist and Truthout contributor James Kilgore calls “carceral humanism,” recasting prisons as treatment facilities to avoid examining the structural forces driving a system of criminalization and punishment.

The deliberations and details of the plans for the new prison are also far from transparent. When Families for Justice as Healing requested public documents on the development of the project, the Division of Capital Asset Management and Maintenance, which is responsible for public building construction, and the state Department of Corrections invoked an exemption on state records, providing heavily redacted meeting minutes. Pages of mostly blacked-out documents do little to assuage concerns that prisons are at odds with public safety, justice and democracy.

During hearings before the state Joint Committee on State Administration and Regulatory Oversight in June 2023, incarcerated people from MCI-Framingham and Souza-Baranowski Correctional Center provided over two hours of testimony detailing the ways in which prison redesign will fail to address the challenges they face in existing facilities and the roots of trauma and harm. They said they had experienced a stark decline in educational programming and job training, difficulty accessing medical and mental health care, and insufficient support for restorative justice and reentry services. There was a palpable sense of frustration with the operations of the Massachusetts Department of Corrections and a consensus that a new prison would only transfer these problems, not facilitate successful return to their communities.

Opponents of the prison moratorium claim the bill would prevent repairs within existing prisons, despite language in the moratorium explicitly allowing for essential repairs. The Massachusetts Sheriffs’ Association’s opposition to the moratorium also insists on the need to “maintain flexibility” in criminal legal reform and rehashes old arguments about maintenance. The repetition of this concern amounts to irresponsible misdirection, bordering on deliberate misinformation.

Repair and flexibility are indispensable concepts, capable of radically altering the criminal legal system — albeit not in the ways that critics of the prison moratorium suggest. It is the process of creating public safety through community empowerment that deserves flexibility, not the repackaging of prison expansion. It is the social contract that is in need of repair, not the bars and cages that infringe upon it.

No amount of effort to redesign prisons can make them viable instruments of justice.

What if our legal system focused on transforming lives, including those damaged by incarceration? Such an endeavor might start by responding to the needs outlined by incarcerated people: the reestablishment or expansion of programs in restorative justice, education, job training and reentry services. Programming within prisons would only be the beginning. Many programs have far better results when conducted outside prison walls, as a thorough review of community alternatives to prison-based therapy has revealed.

Likewise, health and well-being are also best improved outside prisons. Medical care within prisons struggles to provide more than basic harm reduction. The problems of prison health care make a powerful case for the expansion of medical parole and clemency for elderly incarcerated people, reforms that are currently moving forward in the state legislature.

Social repair would also involve a broader plan for decarceration. Examples of large-scale decarceration throughout the 20th century and into the present provide important points of reference for reducing the footprint of the prison system. For instance, a 2018 report by the Sentencing Project describes how five states of differing political orientations were able to substantially reduce the number of people incarcerated by expanding reentry programs, examining sentencing practices and enhancing community-based alternatives. As ambitious as many of these efforts may have been, they focused on short-term strategies and technical reforms. Nonetheless, they revealed that reductions in the numbers of incarcerated people could be achieved swiftly and suggest future possibilities for rethinking systems of punishment.

Repair must also expand the provision of non-carceral social services. Too often, the criminal legal system has been the first or only response to substance abuse, mental health crises, homelessness and gun violence. Many communities, particularly communities of color, receive state resources in the form of spending on incarceration, state supervision, and little else. Approaching social harm from a framework of public health and reparative justice instead of criminal punishment has proven more effective while also reducing the reliance on imprisonment. A reparative approach along these lines might involve a mobilization of resources to create treatment programs and stabilization centers for addiction, build the capacity of unarmed behavioral crisis teams and expand community violence intervention programs. Where these initiatives have remained largely experimental, they can be developed into durable institutions, ultimately supplanting the primacy of prisons. Redirecting the $50 million in funding for new prison construction into these programs would be a bold start.

A reparative approach to justice would grant flexibility to communities to set priorities and define the specific contours of these initiatives. For instance, Families for Justice as Healing calls for a program of “reimagining communities,” establishing mutual aid and creating community-based methods of addressing harm. While the details of such an undertaking would differ from community to community, collective empowerment and deeper democracy would be consistent results.

A five-year reprieve from building prisons and jails opens a new field of possibility, potentially freeing up resources to make a decarceral agenda work. Alternatives to incarceration are abundant and fruitful, requiring time, resources and study to determine the best way forward. It is this transformative process that deserves flexibility as it strives to grow and strengthen social bonds.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser, and we have only 24 hours left to raise $15,000. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.