Part of the Series

The Road to Abolition

On June 24, the architecture and design firm HDR Inc. held what it thought would be a standard event as part of the 2022 American Institute of Architects (AIA) conference at its office in Chicago, Illinois. But the firm, which has designed more than 275 jails and prisons while billing itself as progressive and morally responsible, was met with a powerful presence of abolitionists at its doorstep during the conference.

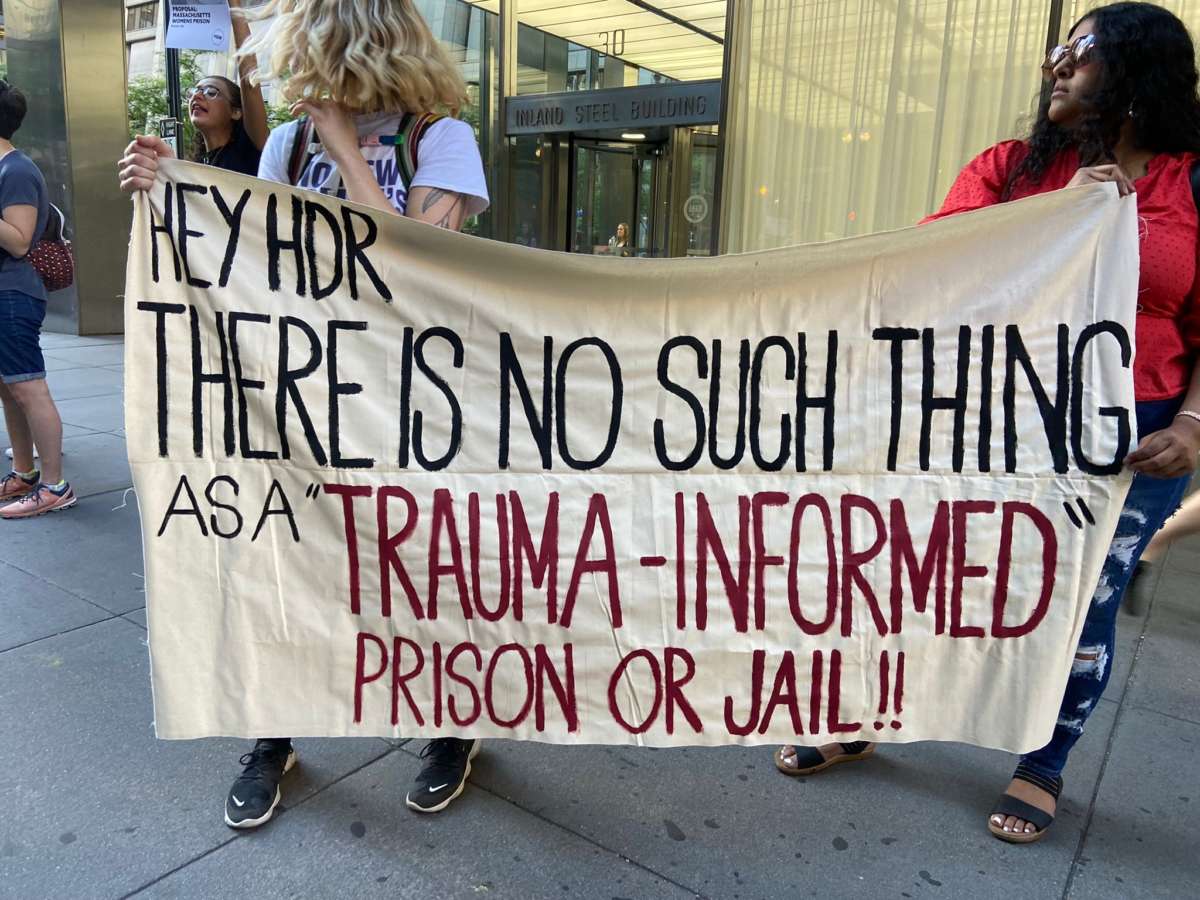

A coalition of formerly incarcerated people and advocates held a banner and passed out flyers to conference attendees while demanding that HDR withdraw its plans to design new carceral facilities and build life-affirming community infrastructure instead. The rally emphasized HDR’s projects that would confine women and gender-expansive people, the fastest-growing segment of the carceral apparatus in the U.S.

“The atmosphere was really charged because that morning, the overturning of Roe v. Wade was announced,” said Navjot Heer, a planner and designer with Design as Protest (DAP), a BIPOC-led collective mobilizing to dismantle power structures that use architecture and design as tools of oppression.

“We ended up being able to talk about how jails and prisons are also a site of reproductive harm and injustice,” she told Truthout, “and about how reproductive justice goes hand-in-hand with abolishing carceral spaces for folks who do have uteruses and experience intense forms of sexual abuse and harm through forced pregnancies, being shackled during those deliveries and being separated from their children through these jails and prisons.”

That morning, the coalition had emailed HDR in an attempt to dialogue with the firm, but HDR’s leadership failed to respond — and it wasn’t the first snub. Building Up People Not Prisons, a coalition fighting to free women from prison and prevent construction of carceral spaces, protested at HDR’s offices in downtown Boston every week for two months in 2021.

“We never heard anything then, and we still haven’t heard anything now,” Sashi James, a member of Families for Justice as Healing (FJAH), a local activist group that leads the coalition, said in a podcast interview with Failed Architecture. “And this is multiple times that we’ve actually met them where they’re at. So, it’s disappointing as a community organizer.”

HDR did not respond to Truthout’s request for comment.

Companies and government agencies are justifying building new prisons and jails by claiming their designs are restorative, outcomes-focused, gender-responsive and trauma-informed. (Trauma-informed jails and prisons are said to incorporate programming that helps women understand their trauma and practices that minimize the likelihood of triggers.) Buildings with natural light, programming spaces, welcoming visitation spaces and staff amenities will improve the quality of life for incarcerated people and staff, according to HDR.

But abolitionist activists and designers say there is no such thing as gender-responsive or trauma-informed jails or prisons, and that carceral facilities will always disproportionately harm poor communities and communities of color.

“I don’t care if you give me Louis Vuitton sheets and house slippers, you know? I’m still in a prison,” Maggie Luna, a lead organizer for formerly incarcerated people with the Statewide Leadership Council in Texas, told Failed Architecture. “I’m still separated from my family, I’m still not being prepared with resources to reenter society successfully, and then I’m still going to have that stigma when I walk out that I have a felony or whatever that I have to take care of.”

Kami Beckford, another designer-organizer with DAP, also said that a “trauma-informed” jail is oxymoronic. “No matter what, a jail will only be a space of harm,” Beckford told Truthout. “You will never find healing when you are isolated from the people that help you feel and be cared for.”

Further, expanding or building new jails and prisons leads to increased incarceration rates, a historical pattern captured in the mantra “If you build it, they will fill it.” HDR could build structures that allow communities to thrive instead of prisons and jails, abolitionists argue.

“We need to build treatment centers in our community, we need to build mental health centers, community centers, parks, schools — everything that other communities have, we need to build the same thing and communities that are under-resourced and over-incarcerated,” said James. “And so it takes a village and we’re building that village, and we need architects to help us build the village. So join the team!”

So far, activists have successfully stalled several of HDR’s carceral projects. In Austin, grassroots efforts pushed commissioners to vote unanimously to reevaluate a strategic plan to build the “Travis County Trauma Informed Women’s Facility,” an $80 million project HDR was designing. Agencies in Massachusetts have been forced to stall their plans on two occasions, thanks to pressure and legal challenges mounted by the Building Up People Not Prisons coalition. Yet in June 2021, Massachusetts hired HDR to create a preliminary design plan for a new women’s prison.

Carceral feminists, politicians and design firms have been weaponizing social justice rhetoric to justify building new jails and prisons for decades. They often attribute tortuous conditions to overcrowded or dilapidated buildings, while abolitionists argue that it’s the inherently oppressive culture of carceral institutions that traumatizes people.

“The culture inside of these institutions is such that every single day, women are either witness to, or the subject of sexual, verbal, and/or physical abuse — and that is driven by the culture,” said Avalon Betts-Gatson, a project manager for the Illinois Alliance for Reentry and Justice. “There is no amount of paint, there is no amount of posh, and there is no amount of anything else that you can use to design away the culture.”

The evidence supports Betts-Gatson and other abolitionists’ views. Jarrod Shanahan’s new book Captives documents how progressive reformers often championed building “safer” jails for women and queer people in New York City and how, again and again, traumatic and violent conditions were reproduced within each new structure. Planners of the Correctional Institution for Women (CIFW) on Rikers Island, for example, promised its new architectural style and colorful walls would improve conditions for women when it opened in 1971. Within months, the jail was investigated for overcrowding and failing to provide basic medical care for confined people. In 1988, the city built a new women’s jail on Rikers Island, named after Rose M. Singer, a feminist who said the jail would be “a place of hope and renewal for all the women who come here.” By 2020, Singer’s granddaughter described the jail as a torture chamber. Now, carceral feminists including Gloria Steinem are pushing for the construction of a new jail for women in Harlem.

The trend is not anomalous to New York. HDR’s York Correctional Facility for Women in Niantic, Connecticut, was touted as “one of the most progressively designed prisons in the country” because of daylight-friendly structures and skylights in a 1997 edition of Architectural Lighting. Nonetheless, several atrocities have taken place at the prison within just the past several years, including rampant sexual assault by correctional officers. In February 2018, a woman at York was forced to give birth to her baby in the toilet of a prison cell.

Similarly, the Western Massachusetts Regional Women’s Correctional Center (WCC) claims to take an approach that is “trauma-informed, gender-responsive, family-focused, and culturally aware.” While some incarcerated people have said WCC is preferable to other local jails, the facility has come under fire for sexual abuse, humiliating conditions and wrongful deaths. In April 2015, formerly incarcerated women at WCC reached a $675,000 settlement with the state for enduring humiliating strip searches in front of male staff. In May 2019, a correctional officer was sentenced to 60 days in jail for having sex with incarcerated women in exchange for Fireball whiskey and cigarettes. One woman testified that she was aware that the officer had the power to revoke her privileges if she refused.

In 2018, 30-year-old Madelyn Linsenmeir died from a treatable infection at a hospital after complaining of unbearable pain and being unable to breathe following an arrest for an outstanding probation-related warrant. Linsenmeir, who suffered from opioid addiction after taking OxyContin at a high school party according to her obituary, was transferred from central booking to WCC where staff members told her “the situation was her own fault for using drugs,” according to a lawsuit filed by Prisoners’ Legal Services of Massachusetts and ACLU Massachusetts. The lawsuit alleges WCC’s staff was acclimated to being deliberately indifferent to the medical complaints made by or on behalf of incarcerated opioid users because their policy was to deny medically appropriate care to people suffering from withdrawal.

Despite these atrocities, the architecture industry continues to design carceral spaces because of the capitalist imperative to profit, often at the expense of the most marginalized.

“Architectural design is really service-oriented. So, you’re serving the client. And the client is the person who has the money and resources and power for these types of projects,” said Heer, the designer with DAP. “In these cases, it would be the DOC [Department of Corrections]. It’s not actually servicing the people who are going to be using that space. The folks who are incarcerated and caged in these spaces are tied to this system of profit. And it is extremely profitable.”

The design industry’s abusive, isolating and lonely culture often sets the stage for company leadership to select oppressive projects without any resistance or input from other workers. DAP is working to facilitate collective organizing among architects and designers to stop oppressive projects like jails and prisons. Several workers at HDR have reached out to DAP in support of their campaign, but they are worried that speaking out at the workplace would jeopardize their employment, Beckford and Heer said.

Ultimately, DAP aims to subvert the power imbalance inherent within the design industry by relinquishing their gatekeeping power and distributing it to the people most affected by their designs. Designers can accomplish this, according to DAP, by immersing themselves within a community and empowering long-standing residents and stakeholders to take control of the design process.

“Communities themselves have a really clear vision about what they need,” Beckford said. “In design school, we are taught that we come and provide the expertise, it’s often like the white savior complex, as if we know what’s best for these communities even if we aren’t from these communities. But communities know what they need best, and that’s what we should be designing instead.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.