Explosive claims in a letter to his lawyers reveal a Gitmo detainee’s fears about his captors’ intentions, well in advance of his mysterious death. Meanwhile, the investigation into his apparent suicide centers on the protocols meant to prevent it.

More than two years before he was found dead in his cell at Guantanamo Bay, Adnan Farhan Abdul Latif reported that the people who oversaw his every move were facilitating his demise.

In a letter sent to his attorneys on May 28, 2010, the Yemeni detainee claimed he was given “contraband” items, such as a spoon and a “big pair of scissors … by the person responsible for Camp 5,” where uncooperative prisoners are sent.

“I am being pushed toward death every moment,” Latif wrote to human rights attorneys David Remes and Marc Falkoff. The communication was written in Arabic and translated into English by a translator Remes has worked with for nearly a decade.

“The way they deal with me proves to me that they want to get rid of me, but in a way that they cannot be accused of causing it,” Latif wrote.

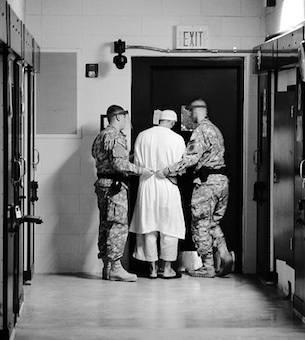

On September 8, Latif was found “motionless and unresponsive” by guards in a cell in the very same Camp 5 cellblock he had cited in his letter. Two months later, the military produced a report that said he committed suicide.

The mystery surrounding the death of the eldest son of a Yemeni merchant who, by all accounts, did not belong at the offshore prison for suspected terrorists, is underscored by the almost prophetic nature of this singular letter.

The question that likely will never be answered is whether it is a true representation of his experiences, the paranoid creation of an unstable mind or the cunning fabrications of an angry man, captured and sold into bondage by post-9/11 bounty hunters.

That answer may have died with Latif, but there is a measure of corroboration for at least some of his claims, and more questions have been raised as the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS) and United States Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) continue to probe the circumstances surrounding his death.

Unanswered Questions

Two weeks ago, Truthout broke the news that the autopsy report prepared by the Armed Forces Medical Examiner concluded the manner of Latif’s death had been ruled a suicide. Truthout sought a copy of the autopsy report under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). Last week, John Peterson, the head of the US Army Medical Command’s FOIA office, denied Truthout’s records request stating, “the autopsy report …is part of an ongoing Naval Criminal Investigation and is not releasable” under a FOIA exemption “which prohibits the disclosure of information that could reasonably be expected to interfere with an ongoing law enforcement investigation.”

Following up on Truthout’s story, The New York Times reported Latif died from an overdose of psychiatric medication that he may have hoarded until he collected enough for a lethal dose.

Truthout has independently confirmed with officials who have seen the autopsy report that it states Latif took a fatal dose of psychiatric medication.

Latif had been seriously injured in a car wreck in his native Yemen and was in search of free medical treatment in Afghanistan when he was captured and sold to the Northern Alliance following the terrorist attacks on the Pentagon and the World Trade Center.

He suffered severe brain injuries in the car accident, which left him with ongoing neurological problems and may have contributed to behavior that led to repeated stays in the detention center’s psychiatric unit.

Latif had been cleared for transfer back to his homeland four times over the past decade by both the Bush and Obama administrations; yet he remained imprisoned at Gitmo, his case mired in legal and political entanglements that Remes, his Washington, DC-based lawyer has been trying to unravel since 2004.

The 36-year-old Yemeni husband and father of a 14-year-old son had a history of suicide attempts, but also had reason in recent months to find hope amid the despair: A human rights group had taken up his cause.

One of the most compelling questions investigators must resolve is: How would Latif have managed to hoard and deliberately overdose on pharmaceuticals at a prison facility where detainees are under constant surveillance?

The well-defined protocols in place at Guantanamo were specifically designed to prevent such an occurrence – so the question of whether those protocols were followed is yet another element of the investigation into Latif’s death.

Standard Operating Procedures

Camp Delta replaced the crude open-air cages where detainees were first held when they were brought to the prison in 2002. Camp Delta was made up of Camps 1 through 6, as well as a psychiatric ward, a camp that houses high-value detainees formerly in custody of the CIA and several other camps. As the population of the detention facility dwindled over the years, some of the camps were shuttered. But the official procedures remain in place.

Guantanamo’s 2004 Camp Delta Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) manual, released publicly by the Department of Defense several years ago, states that even in one of the prison’s lower security camps, which has since been closed, “MPs will verify a detainee has taken their medication, if orally, by making the detainee open their mouth and move their tongue around as to check all areas for hidden medications.”

Additionally, “All MPs will make detainees open their hands before leaving … to ensure no medications that are to be taken orally are being hidden.”

Those checks are still in place throughout Guantanamo and are now conducted by Navy Corpsmen.

At the detention hospital, where Latif was held prior to his death, a separate October 2004 SOP pertaining to the administration of medications to detainees states that corpsmen are to “visualize the detainee has actually swallowed his oral medications” before they leave the “cell area.”

According to the SOP, corpsmen are authorized to administer or “pass” medications after they have completed a five-day training course known as the “Corpsmen Medication Orientation to Camp Delta.”

Corpsmen are then required to sign a “Medication Administration Understanding,” which states they will comply with the requirement to witness the swallowing of medications and also will not “leave powders, medication bottles, pills, lotions or any other medical material in a detainee’s cell for use at other times unless I have specific permission from the RN/MD/DOC via a memo on file at the DOC [Detention Operations Center].”

The Camp Delta SOP also requires the guard force to randomly search prisoners’ cells on “day shift and swing shift,” at least three times a day and prisoners are also searched, “at a minimum,” every time they are removed from a cell. If Latif had successfully managed to hoard his medications, despite visual inspection of his taking the drugs, he would have had to evade all the mandated searches of his cell and his body.

Moreover, the Camp Delta SOP states that prisoners like Latif, who are deemed to be a “self-harm” risk, are supposed to have their activities documented every 15 minutes. Guards are to “conduct a visual search of the cells and prisoners every ten minutes by walking through the block.” Deviating from the SOP is considered to be an Article 92 violation – failure to obey an order or regulation – under the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ).

Latif had expressed his desire to take his own life and had even attempted suicide several times during the course of his 10-plus years of imprisonment at Guantanamo. But Remes questioned whether he could have eventually succeeded in doing so, at least without assistance, given the tight security measures in place.

Joint Task Force-Guantanamo (JTF-GTMO) spokesman Capt. Robert Durand did not respond to specific questions regarding the SOPs and whether JTF-GTMO staff has followed them.

A Recalcitrant Prisoner, a Pantheon of Drugs

As Truthout reported in October, Joint Task Force-Guantanamo did not immediately issue a statement about Latif’s cause of death – unlike previous deaths at the prison, including those the government said were the result of suicide – because there were no obvious signs as to how he died.

It’s also unknown how long Latif was unresponsive in his cell before guards discovered him unconscious. A US official knowledgeable about the NCIS investigation into Latif’s death told Truthout Latif did not leave his cell to attend prayer on the day of his death, and did not eat breakfast or lunch.

In a statement issued to Truthout a month after Latif’s death, Durand said there was no “obvious indication of self-harm” or “a known medical condition” that Latif suffered from. Durand went on to say that Latif “was monitored by the behavioral health unit, and his recent actions, activities and statements to therapists indicated he did not appear to want to end his life.”

Durand added that JTF-GTMO only issued statements when there was a “clear and reasonable assumption” about the manner in which a prisoner died, such as “hanging … slashed wrists or scattered pills from an attempted overdose.”

Durand’s statement indicates there weren’t any pills Latif’s body when he was found.

In fact, Latif, who had a history of being a “noncompliant” prisoner, expressed his concern on more than a dozen occasions over the course of eight years regarding the medication he was administered, which he said was changed every four to six months.

“People stop trusting the medication, for example sometimes they give you the wrong quantity of medicine or wrong medicine,” he said during a June 18, 2005 meeting with Remes.

Latif described being strapped to a “hard stretcher” and transferred back and forth from his cell to the medical clinic over and over again, in what he said was a form of sleep deprivation. At other times, he claimed he was kept medically sedated, even being drugged “in the night when I was asleep.” A note by the attorney at this time indicated Latif was being medicated on “sedatives and psychotropics [and] painkillers.”

Remes told Truthout in early October that the government’s idea of medical treatment was simply to keep Latif subdued. “On many occasions he told me he was drugged and sedated,” Remes said. “When he met with me he told me he was given energy boosters or mood boosters.”

Latif also told Remes during another meeting they had in May 2010 that following a suicide attempt, Guantanamo officials blamed Remes for it.

“They came to talk with me,” Latif said. “They asked why I did this. They suggested that you [Remes] had encouraged me to do this.”

Latif said he also was visited in the psychiatric ward by “two military lawyers” who encouraged him to fire Remes and asked him “to sign a paper firing you [Remes],” which he refused to do. The same incident also happened in January of 2010, Latif said, except that time Latif claimed he was given an injection prior to being visited by a military lawyer who wanted him to fire Remes. Latif said he believed “they wanted to have no one report” his death.

According to unclassified notes taken by Remes in May, during his last meeting with his client, Latif said he sometimes took psychiatric medications out of his mouth “because I don’t want to here.” A word in Remes’ notes is missing. He said it may be “die.”

In the days leading up to his death and his transfer to Camp 5, Latif, who was held in the detention hospital at the time, was reportedly threatened with an “ESP injection,” according to an account given to Remes in October by Shaker Aamer, the last British prisoner whose ten-plus years of detention and torture at Guantanamo has attracted international attention and put pressure on the British government by human rights organizations to secure his immediate release.

Aamer was Latif’s “neighbor” in Camp 5, Alpha Block. It is unknown what an “ESP injection” is, but Aamer claimed other prisoners said it “makes you a zombie,” and has a “one month afterlife.” Neither Durand nor other JTF-GTMO officials have responded to Truthout’s requests for comment about the drug.

In July – three months prior to Latif’s death – Truthout obtained through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request an inspector general’s report from the Department of Defense that revealed “war on terror” prisoners in the custody of the US military at Guantanamo and elsewhere were forcibly drugged with powerful antipsychotics and other medications, and also subjected to “chemical restraints” if they “posed a threat to themselves or others.”

Lt. Col. Todd Breasseale, a Defense Department spokesman, told Truthout earlier this year that secrecy rules prohibited him from identifying exactly what “chemical restraints” are and whether they are still being used at the prison. The report only identified the powerful antipsychotic, Haldol, which can be administered by injection.

Over the past decade, dozens of current and former prisoners held by the US government in Guantanamo, Iraq and Afghanistan have alleged in news reports, court documents and meetings with their lawyers, that they took pills against their will and/or were forcibly injected with unknown substances that had mind-altering affects during or immediately prior to marathon interrogation sessions.

The allegation sparked an investigation by the CIA and Defense Department inspectors general, which prepared a report on its findings. While the watchdog said it could not find any evidence that “mind-altering” drugs were used for the purposes of interrogation it noted that “certain prisoners, diagnosed as having serious mental health conditions being treated with psychoactive medications on a continuing basis were interrogated.”

The CIA version of that report remains classified.

Truthout’s investigative expose on Latif’s life and death, published in October, quoted renowned forensic pathologist Cyril Wecht, who suggested the US government likely would conclude Latif’s death was due to drugs – specifically, drugs that cause brain depression like opioids, benzodiazepines, anti-depressants and anti-anxiety sedatives – the kinds of drugs that appear to have been a routine part of life at Guantanamo for the recalcitrant detainee.

Aamer also claimed, according to Remes’ notes of his interview with the prisoner, that Latif had “fought and fought” his transfer to a particular cell in Camp 5 because of the constant buzzing noise from a generator located behind a wall.

In his May 28, 2010 letter to attorneys Remes and Falkoff, Latif said he had been placed in isolation “in block Alpha, Camp 5, in a cell that resembles a lion’s cage. It has been made especially for me in this way.”

He said drugs apparently administered to him for sedation affected him in such a way that he ate his own excrement.

That letter also contains other allegations, notably the claims that Latif was given items that might help facilitate his suicide, as well as threats to Latif’s life, more than a dozen beatings by Guantanamo’s brutal Immediate Reaction Force (IRF) squad, which he says resulted in broken bones, and a visit to the detention hospital.

“I don’t think anyone believes me but this is the truth to be found by people who investigate what is happening to me especially these days,” Latif wrote. Of the incident with the scissors and spoon, Latif said he was told to report it to “the police” and that “a chief in the navy who is specialized in investigating such incidents was called.”

Other prisoners represented by Remes have leveled similar allegations of what they said were attempts to facilitate their suicide. In late July 2009, a year before Latif said scissors were placed inside of his cell, Abdulsalam al-Hela also reported finding scissors and sharp metal objects in his cell. Yasin Esmail told Remes he heard of other prisoners having similar experiences.

Breasseale, the Department of Defense spokesman, said Latif’s allegations are “absurd” and he would not respond directly to them.

“The suggestion that DOD personnel, the overwhelming majority of whom serve honorably, are or ever were engaged in systematic mistreatment of detainees is patently false and simply does not withstand intellectual scrutiny,” he told Truthout.

“While there have been substantiated cases of abuse in the early days of the detention facility, for which US service members have been held accountable, our enemies also have consistently employed a deliberate campaign of exaggerations and fabrications.

“I will say that the detention facility at JTF Guantanamo Bay happens to be one of the most heavily scrutinized in the world. Accusations that the professionals who are charged with conducting the safe, humane, legal and transparent care and custody of the detainees there perform in any other than the most professional of ways simply fails to hold up under investigative rigor. Further, we have years ago updated our laws, policies, procedures and training to ensure respect for the dignity of every detainee in our custody. We never forget that the physical well being of detainees is our primary responsibility, and their security is of vital importance to our mission. Frankly, we fail to prioritize this duty at our own peril….”

Despite past statements of suicidal intent, Latif became a bit hopeful when he learned human rights organizations were going to launch a campaign to free him.

Remes told Truthout that he was told by Amnesty International in an email in July that “the cases of Adnan Latif and Hussain Salem Mohammed Almerfedi have been selected for this year’s Amnesty International Letter Writing Marathon, an annual international activism drive that takes place in December and generates a lot of appeals and media attention.”

On August 2 – a month before Latif’s death – Remes said he met with officials at the Yemen Embassy and “pressed them to give priority getting Adnan and another client, Abdulsalam al-Hela, out of Guantanamo.”

Remes said the Yemen officials agreed, “expressing particular sympathy for Adnan.”

Soon after, he said he sent both Latif and al-Hela a letter “informing them that the embassy would make them a priority.”

“I Am a Human Being”

What continues to go unexplained is why Yemen has yet to accept Latif’s remains three months after he died. At first, a Yemen government official told Truthout Latif’s remains would not be accepted until the government received a complete copy of his autopsy report, as well as the conclusions of the NCIS investigation into his death.

William K. Lietzau, the assistant secretary of defense for detainee policy, turned over the autopsy report to Yemen Embassy officials in Washington, DC on November 10. Yemen then sent a copy of it to Sana’a, the country’s capital. Not long after, Yemen government officials said they agreed to accept Latif’s remains and turn them over to his family due to the amount of time it would take NCIS to complete their probe.

Two weeks ago, a Yemeni government official told Truthout Latif’s remains would be returned to his family in “the upcoming days.” But at press time his remains continue to be held at Ramstein Air Base in Germany and it is unknown if Yemen will ever accept them.

Breasseale would not respond to questions about what, if any, contingency plans are in place if Yemen refuses to accept Latif’s remains. Yemen government officials previously told Truthout “politics” were the reason his remains have yet to be repatriated to Yemen. But they would not elaborate.

What is certain, however, is that Latif’s younger brother, Muhammed, said his family will not accept his brother’s remains until they receive a complete, unredacted copy of his autopsy report, which the Yemeni government has refused to turn over to him. The report likely will identify the fatal dose of psychiatric drugs Latif is said to have taken and that’s something the US government wants to keep secret, officials close to the investigation have said.

Truthout’s attempts to pry loose the identities of other drugs given to detainees have failed. The list of drugs given to prisoners would be found in their medical records. But the US government has consistently refused to release those records under FOIA citing prisoners’ privacy rights.

Even the prisoners’ attorneys have had trouble gaining access to the medical records. When they do obtain the documents, they are deemed either “protected” or classified and are therefore unable to discuss publicly what it says about drugs the prisoners were given.

Another investigative report published by Truthout in 2010 found that all prisoners rendered to Guantanamo were given a massive dose of the controversial antimalarial drug “mefloquine,” regardless of whether they had malaria or not. An Army public health physician said the dosage given to prisoners amounted to “pharmacologic waterboarding.”

Mefloquine is known to cause severe neuropsychiatric side effects, including suicidal and homicidal thoughts, hallucinations and anxiety.

“They [the Yemeni government] are playing this game not giving all of the information and sometimes giving us wrong information so that we will give up and stop asking about my brother,” Muhammed said. “But by God we are not going to forget about this matter at all. We will follow this through until the end.”

Muhammed also said his family wants a second, independent autopsy to be conducted to confirm the cause and manner of his brother’s death. However, he said the Yemen government might pressure the family to immediately bury his brother if and when they turn over his remains. Also complicating the possibility of a second autopsy is the condition of Latif’s remains. US officials told Truthout they are badly decomposed.

The mystery surrounding Latif’s death has led Amnesty International and other human rights organizations to call for an independent investigation.

Steve Schorno, a spokesman for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in Washington, DC, which has been conducting frequent checks on prisoners at Guantanamo, said the ICRC “is deeply concerned about Mr. Latif’s suicide and the continuing uncertainty faced by detainees in Guantanamo Bay.”

But Schorno said the ICRC “will not comment on US government investigations or the reported need for independent investigations into his death.”

“As a matter of policy, the ICRC does not conduct investigations, including in cases of suicide by a detainee,” Schorno said. “The issue of Mr. Latif’s suicide is one we have followed and continue to follow as part of our bilateral, confidential detention dialogue with US authorities.”

Schorno said the ICRC has had numerous conversations with Latif’s family since his death three months ago.

Latif openly expressed his belief that no one would believe his story about the systematic abuse he had endured, and that he expected he would end up dead amid mysterious circumstances.

“It seems that I might have to send you my body parts and flesh to make you believe me and to believe to what degree of misery I have reached,” he wrote in that May 28, 2010 letter to Remes and Falkoff. “I am happy to die just to get away from a non-extinguishable fire and no-end torture. Marc and David: In the end, I am a human being.”

Our most important fundraising appeal of the year

December is the most critical time of year for Truthout, because our nonprofit news is funded almost entirely by individual donations from readers like you. So before you navigate away, we ask that you take just a second to support Truthout with a tax-deductible donation.

This year is a little different. We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. 2025 was a year of frightening censorship, news industry corporate consolidation, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We’ve set an ambitious target for our year-end campaign — a goal of $250,000 to keep up our fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout before December 31. If you have the means, please dig deep.