In April 17-18, 2015, I attended a conference in Orlando, Florida. Beyond Pesticides, a non-profit environmental organization in Washington, DC, since 1981, sponsored the forum.

Before the conference started, some fifty people took a bus tour of rural Florida, especially exploring the lush agricultural region around Lake Apopka, Florida’s fourth largest lake. I entered the bus with apprehension. I had heard bad things were taking place in central Florida.

Our guide, Jeannie Economos, has been working for the Farmworker Association of Florida for about twenty years. She is the embodiment of a person living the ecocide and brutality of the agricultural economy of Florida. She fiercely defends the dignity and human rights of farm workers.

Economos knows the history and politics that shape Lake Apopka. She shines in virtue. Listening to her one has little doubt that behind the facts there’s a grave injustice hovering over all of Florida.

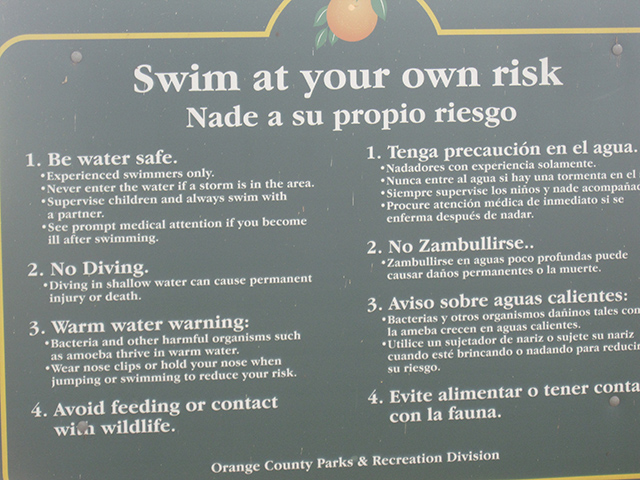

Lake Apopka warning sign. (Photo: Evaggelos Vallianatos)

Lake Apopka warning sign. (Photo: Evaggelos Vallianatos)

That injustice has two faces.

First, Economos said, Florida plundered Lake Apopka in ways hard to fathom. During World War II, the state allowed farmers to slice about 20,000 acres of land from the lake. The farmers then converted the rich muck soil into vegetable factories. But the pollution of those industrialized vegetable farms nearly killed the lake. So, in the 1980s, the state of Florida bought off those lake farmers, hoping without hope to save the lake.

In 2015, Lake Apopka is moribund. Its wildlife has been dwindling, verging on extinction. The farmers’ addiction to biocides and synthetic fertilizers nearly wiped out lake fish and birds alike. In 1998, about 1,000 fish-eating birds died from poisoning. The poisons that killed the birds were primarily DDT-like sprays.

The alligators of Lake Apopka mirror the deleterious state of the lake. The maladies of alligators are maladies of the ecosystems poisoned by industrial agriculture and other industries surrounding the lake. The alligators fail to reproduce.

When the conference began, professor Louis Guillette, who taught for many years at the University of Florida and now is teaching at the Medical University of South Carolina, explained how and why poisons in the lake cause reproductive and sexual abnormalities to alligators and other water animals. Pesticides castrate alligators. Guillette should know. He made his scientific career by studying the decline of alligators of Lake Apopka.

Farm worker. (Photo: Evaggelos Vallianatos)

Farm worker. (Photo: Evaggelos Vallianatos)

Another scientist, Professor Tyrone Hayes of the University of California-Berkeley, told us that pesticides cause havoc to wildlife, especially amphibians. Hayes explained in graphic detail how the “popular” weed killer atrazine disrupts the lives of frogs. Atrazine in minute amounts feminizes male frogs; indeed, it castrates them.

Hayes said those who spray atrazine have about 22,000 as much atrazine in their body than the amount castrating frogs. He did not mince words telling us of his persecution by the owners of atrazine.

Out in the fields near Lake Apopka, we could see signs of the collapse of nature. But we could also see additional signs of business as usual. The land next to the sick lake is littered with medical incinerators, tree and vegetable and flower “nurseries,” factories, large farms and real estate development.

These businesses, especially abandoned factories that used to manufacture pesticides, have a dominant, toxic, footprint on the natural world. The chemical factories contaminated the land and lake so heavily that the government calls them “superfund” sites. Spending billions and decades, the government then outsources the clean-up of the worst pollution.

No wonder our tour of Lake Apopka was a “toxic” tour.

The second salient feature of present-day Lake Apopka is farm workers, thousands of them living around the lake. These farm workers live lives full of poverty, disease and death. Economos spoke with anger about the oppressive, slave-like conditions of farm workers. These destitute people are largely black and Hispanic. They have been working for decades, creating wealth for Florida’s rural oligarchy.

Economos repeated a slogan a rural oligarch was supposed to have said: “We used to buy slaves; now we rent them.”

Employing or renting slaves did not save the Apopka farmers. The state put them out of business in 1998. But the state did nothing for the farm workers who had worked in the farms of Lake Apopka for about fifty years. Suddenly, farm workers lost everything. Some of them even became homeless.

“The state spent hundreds of millions on the lake,” Economos said, “but not a dime on the farm workers.” And the University of Florida is not better than the state. It has a Food Research Institute next to the lake, but it does not see the farm workers.

Farm near Lake Apopka. (Photo: Alen Cohen)

Farm near Lake Apopka. (Photo: Alen Cohen)

This toxic tour and stories of ecocide and mistreatment of those who harvest our food brought me back to 1979 when I joined the Environmental Protection Agency. I started my work by examining the science and policy around “farm worker protection.” To my horror, I learned that farmers sprayed their crops with carcinogens and brain-damaging toxins. Farm workers would then be ordered into those poisoned farms to harvest the fruit or vegetable or corn.

I complained to senior EPA officials in vain that this treatment of farm workers was both hazardous and morally reprehensible. EPA issued its Farm Worker Protection Standards, a lipstick measure leaving the toxic environment of industrial agriculture intact.

Farm workers still do the most dangerous work in America. They deserve better. In fact, they deserve land rather thanslavery. Help them to become family farmers to raise our food and strengthen our democracy.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser, and we have only 24 hours left to raise $17,000. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.