In Joseph Stiglitz’s new book, “The Price of Inequality: How Today’s Divided Society Endangers Our Future,” the Nobel Prize-winning economist argues that there is a price to be paid for economic inequality. You can obtain a copy of Stiglitz’s latest economic analysis directly from Truthout right now by clicking here.

What will life look like down the road if we don’t reverse economic inequality? We must see through the myths of capitalism and build a mass movement if we are to save ourselves.

Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, one of America’s most prescient voices, wrote an article for Vanity Fair several months before Occupy Wall Street was born. “Of the 1%, by the 1%, for the 1%” called attention to the widening gap between rich and poor and its deadly impact on our society and its democratic institutions. In his newly released book, The Price of Inequality, Stiglitz returns to this theme of a divided society, delving into the origins and consequences of economic unfairness. I caught up with Professor Stiglitz and talked to him about how the persistent myths and beliefs associated with our capitalist system help to drive this trend, turning America from a land of opportunity to a land of broken dreams.

Lynn Parramore: An argument has been made, particularly since the end of the Cold War, that capitalism is great at producing things that can improve our lives, and so we ought to therefore tolerate some unfairness. What’s wrong with that narrative?

Joseph Stiglitz: Well, capitalism does have a lot of strengths, including producing things that are very innovative. But what drives capitalism is the profit motive. You can profit not only by making good things, but also by exploiting people, by exploiting the environment, by doing things that are not so good. The narrative that you describe ignores the extent to which a lot of the inequalities in the United States are not the result of creative activity but of exploitive activity. And if you look at the people at the top, what is so striking is that the people who’ve made the most important creative contributions are not there.

By that I mean the really foundational things like the computer, the transistor, the laser. And how many people at the top are people who made their money out of monopoly — exercising monopoly power? Like bankers who exploited through predatory lending practices and abusive credit card practices. Or CEOs who took advantage of deficiencies in corporate governance to get a larger share of the corporate revenues for themselves without any regard to the extent to which they have actually contributed to increasing the the sustainable well-being of the firm.

LP: How does our current situation compare to other eras in terms of the differences between ordinary Americans and the richest among us?

JS: Doing a precise comparison is difficult because we don’t have data sets that go back that far. But we do have data sets that go back more than 30 years and what is clear is that the share of the top 1 percent has almost tripled since 1980. So, this kind of inequality at the top has unambiguously gotten much, much, much worse. We also have data on the extent to which there’s been a hollowing out of the middle class. The data that recently came out from the Fed indicated that we’ve wiped out 20 years of increases and wealth for the middle American.

LP: So for most of us, 20 years of economic progress just went up in smoke. But the super-rich are doing very well. What happened?

JS: It’s the peculiar nature of the American economy, which is that’s it’s a very powerful machine that is working for a very few people, and has not been delivering for most Americans. If you had an economic machine that worked the way it was supposed to, everybody would be getting better. And an economy that’s normally growing, say, 3 percent, even over a 20-year period. Steady accumulation would lead to their wealth more than doubling in that period. And it clearly hasn’t happened. And adjusted for inflation, it would have even increased even before, unadjusted for inflation, would have increased it even more. And that clearly hasn’t happened.

LP: There’s a persistent myth that America is still the “land of opportunity.” Why is that myth so prevalent, even in the face of so much evidence to the contrary?

JS: Well, there are two reasons for this. One of them is that the myth is so much part of our sense of identity as Americans that it is devastating for us to give it up — for us to say we are less of a land of opportunity than old ossified Europe. It was one of the things we were most proud of, and clearly, it’s not true. When you have something that’s so inconsistent with your self image, it’s really, really hard to face the facts.

The second reason has to do with the nature of evidence. Everybody know examples of people who make it from the bottom or the middle-bottom to the top. And our press talks about them. The media calls attention to the successes. But when they call attention to successes they don’t say this is one of a million or one of a thousand. In fact, the reason they write about it is because they are so unusual. If most people did it, it wouldn’t be an unusual story. So, in a sense that’s how our media works. It encourages us to think of the exceptions as the norm.

LP: Some say that if we redistribute income in a more equitable way, people won’t want to work as hard. Is that true? What happens to our motivation to work when things are so inequitable?

JS: One of the myths that I try to destroy is the myth that if we do anything about inequality it will weaken our economy. And that’s why the title of my book is The Price of Inequality. What I argue is that if we did attack these sources of inequality, we would actually have a stronger economy. We’re paying a high price for this inequality. Now, one of the mischaracterizations of those of us who want a more equal or fairer society, is that we’re in favor of total equality, and that would mean that there would be no incentives. That’s not the issue. The question is whether we could ameliorate some of the inequality — reduce some of the inequality by, for instance, curtailing monopoly power, curtailing predatory lending, curtailing abusive credit card practices, curtailing the abuses of CEO pay. All of those kinds of things, what I generically call “rent seeking,” are things that distort and destroy our economy.

So in fact, part of the problem of low taxes at the top is that since so much of the income at the very top is a result of rent seeking, when we lower the taxes, we’re effectively lowering the taxes on rent seeking, and we’re encouraging rent-seeking activities. When we have special provisions for capital gains that allow speculations to be taxed at a lower rate than people who work for a living, we encourage speculation. So that if you look at the design bit of our tax structure, it does create incentives for doing the wrong thing.

LP: When ordinary people see this speculation and unfairness, do you think it disincentivizes them to work harder, to take risks?

JS: Oh, very much so. It has a very enervating effect on our society and our economy. I describe experimental results in in my book where peoples’ incentives to work hard are reduced when they believe they are part of an unfair system.

LP: We also hear that deregulation and downsizing government is somehow supposed to make capitalism work better for all of us. Why has that persistent belief failed us?

JS: A lot of these are questions about perception. To the extent that we can see waste, obviously we say that if we could get rid of that waste, we would be a better economy. By definition, waste is waste. The Republican rhetoric has focused on waste in the public sector. But waste, at some level, is an inherent consequence of human fallibility. We’re going to make mistakes, and that’s going to be true in the public and the private sector. No government program has ever wasted resources on the scale of America’s private financial sector in the run-up to the crisis. So the first thing you realize is there is waste everywhere including in the private sector.

Now if you ask people about things there are important to them … obviously they care a lot about the school their children go to. They worry about too-large classes. They worry about police protection. Those are all things that people value a lot. They value the Internet, which was created by government-funded research. Health care and drugs were are all based on government-funded research. So the bottom line is that government services have proved highly valuable. And this is where the big lie, the big distortion is. By talking about the few instances of inefficiency, they try to direct the attention away from the teachers, the policeman, the fireman, the researchers, the people building the roads to make our society function. And they turn our attention away from the failures in the private sector.

LP: What is the connection between the increase of deregulation and the rise of inequality?

JS: I think there are a couple of things going on simultaneously. The most important aspect for deregulation was in the financial sector. And that deregulation led to this over-bloated financial sector, predatory lending, abusive credit card practices and so forth. That did double function. It lead to more wealth at the top. It took away wealth and income from the bottom. So that really was very bad for American inequality. Not good for American economic growth. So that’s one aspect of it.

Deregulation was, in part, the result of an ideology. A lot of weight was given to the business community and the people of the top. Corporations and the one percent. It reflected the increasing influence of money in politics. That itself again led to more inequality. Under Bush, you get bills where the government said that it would not bargain with the drug companies, giving the drug companies over a half trillion dollars over 10 years, lowering progressive income taxes, special provisions for capital gains and dividends. Things in turn which created a more distorted economy and a more unequal society. So some of the forces that gave rise to deregulation gave rise to these other activities that also gave rise to inequality.

LP: Obviously there are lot of costs that this inequality imposes upon us. What, in your view is the biggest cost, particularly to young people?

JS: One aspect of it is the problem about student debt. Market forces are global. America’s inequality is distinctive because of the way we shape those market forces and a good example are our bankruptcy laws which are the kind of laws that regulate our economy. Our bankruptcy law gave priority to the banks, to derivatives, to risky products and AIG and so forth. But when you do that, you expand risk-taking by the banks. You encourage the banks to go into risk, into gambling, rather than into lending.

At the other extreme, we passed a change in the bankruptcy code. There’s a provision that students in bankruptcy cannot discharge their debt — even if the school doesn’t provide what was promised. Then you combine that with this austerity going on today, where we’re forcing many of the states to raise their tuition enormously. So what you have is the situation in which the students who want access to education have no choice but to borrow. Their parents’ incomes are doing very badly, and yet if they borrow, there’s no way, no matter what they do, to get out from under this debt. Even if their education doesn’t pay off. That’s compounded by the fact that we have this very high unemployment, and particularly high youth unemployment. And data show very clearly that if a young person graduates from college in a period in which there’s high unemployment, the income prospect for your entire life is going to be greatly diminished.

LP: You’ve talked about the corruption in our political system. What is our best hope in the political realm of reversing this trend in economic inequality?

JS: On the positive side, let me just say that there are a number of reasons for hope. One of them is that if we look at countries like Brazil that seemed to be over the precipice, people saw where it was going and the country came together and did things like education under Cardoso. And hunger and nutrition and health programs. You can already see in the data that inequality has been coming down. The United States faced high levels of inequality in the Gilded Age, in the period in the Roaring ’20s. But it backed off. The social legislation of the ’30s reversed the trend. So there is hope that societies that are moving in this direction that we’ve been moving will see the light and change.

And there’s lots that you can do. In my book, I described this very comprehensive economic agenda. It’s not hard. And you don’t have to do everything. What I try to put forward are two hypotheses of how that might happen. In one of them, what I call the “1 percent” will finally realize that it’s in their enlightened self interest, rightly understood, to care about the rest of society. You cannot do well at the top of the pyramid unless the base of the pyramid is strong. And the other one is that the 99 percent realize that they’ve been sold a bill of goods. And they realize that some of these ideas that we’ve been talking about — trickle-down economics that destroy the interests of the poor, the middle class — are just wrong. They come to realize that the United States is not the land of opportunity, that the United States has higher level of inequality of any of the other advanced industrial countries. As they come to realize this, then maybe they’ll wake up and say, why is that?

LP: And if we wake up, if we understand it, how do we get our politicians to listen to us? What can we do to fix our political system?

JS: Well, you know, just as in the case of the economic agenda, I don’t think there is any single magic bullet that is going to make a big difference — one that will be definitive. There are lots of things. Economic inequality has many dimensions and has manifested in many levels of our complex political system. I guess I have to believe that the single thing that probably distorts our democracy the most is campaign finance. So that would be a place to start. Public funding of all campaigns would probably take away a lot of the power of money.

So in one way, you have to ask the fundamental question, how is it that we’ve become a country that’s more accurately described as one dollar, one vote, than one person, one vote? And one has to say it has something to do with that power of money in the political process. There are other changes in legislation that would make a great deal of difference. We have a system where you need a lot of money to get out the vote. So if you went to the Australian route, and said you have to vote, that would also have an impact.

LP: I want to paint a picture, particularly for the young people. What might life actually look for them 20 years down the road, 30 years down the road, if we can reverse this trend? And what might life look like if we don’t?

JS: Let me step back and say that economists always like to think about the counter-facts or what life would be if we go down one course versus another. We’re not gonna to be entering the Garden of Eden. But if we go down the route that we’re going, we’re going to a world where people live in gated communities. We already have by far the largest fraction of our population locked up in prison. We will have an increasingly insecure society. Americans will be facing insecurity, of economic insecurity, healthcare insecurity, a sense of physical insecurity. We will be worrying politically about the role of extremism. Extremism on the right, extremism on the left. So that’s the kind of picture that I can see as going down towards. I see so many other countries that have these divided societies going down this directions.

The other one is a society where most Americans are actually better off. I mean, the reality is that Americans are wonderfully optimistic. Even when things are not going very well, they’ll smile and say well, you know, we’re just having a temporary setback. A 20-year, zero-increase in wealth is not a small setback, and so I think the alternative is that they can see a world in which our increasing wealth is more equitably shared, and that will be a world where they will have more security, more wealth, more time to spend doing what they really care about. Some individuals will be absorbed in their work, other individuals will have sufficient income that they’ll be able to have a hobby. A society in which everybody will be able to exercise their creativity in their own way.

LP: Has there been any reaction to your book that you didn’t anticipate as you were writing?

JS: I guess the thing that was most moving in a number of the talks that I’ve given is the large number of young people that have come to the microphone and asked questions where you can sense their sense of despair, their sense of frustration at being saddled by student loans, their sense of job prospects being not very good. A couple of them really articulated a sense of unfairness. One kid said “To get a job, you have to have an internship. I don’t have the connections. I don’t have the money to live on to accept one of these low-paying internships.”

And then another one said “You know, to get a job now, you need a master’s degree. I can’t afford it. I already have too much student debt.” And these were, you know, intelligent kids, who obviously played by the rules, done everything right, worked hard at school. But they were hitting the kind of frustration that you shouldn’t be getting from young people. To me, that was really heart-rending. And it came from not just one kid. Not in just one talk.

LP: Do you sense that they have energy for action? Political action or participation in social movements?

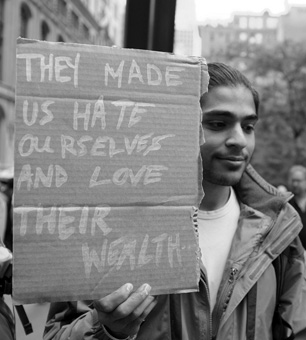

JS: I don’t see them enervated. These are kids who have not dropped out. They really have a thirst. They want to know what could we do. But I didn’t get the sense that they felt very confident that either the political system or protest movements work. So they were expressing a sense of frustration, despair, that, you know, “Occupy Wall Street didn’t work, the political system hasn’t been reformed, the economy’s not functioning, we’re saddled with these debts, job prospects are bleak. And, we don’t have the money like a rich kid to stay in school. What do we do?”

LP: And what’s your answer to them?

JS: Well, all I can say is that I just felt enormously empathetic with them. And I think the only hope at this point is to try to get political activism, including protests like Occupy Wall Street. But also engaging in the political movements. Or trying to make the protest movements more linked to our political process.

LP: When you were saying that young people felt a sense that Occupy Wall Street didn’t work, do you think that’s really true?

JS: I think it did move the conversation. What is clear is that it hasn’t yet reached fruition. It did move the conversation, but certainly, in the context of one of the political parties, things haven’t really changed where they’re going. It may have succeeded in getting President Obama to talk a little bit more forthrightly about the problems of inequality in our society. And in that sense, it has made, I think, Americans more receptive to the fact that economic inequality is one of the major problems we’re facing today.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.