Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

Editor’s note: This is the first story in our Clearing the Air series about shale gas drilling in Penn Township. PublicSource has followed the events there since April 2015. We placed air quality sensors at five homes to monitor pollutants near the contested well pad for two months. The data collected are being analyzed. PublicSource will share the results with residents and report on what we found. Sign up for our newsletter to ensure you receive our next story.

Gene Meyers asked everyone to join him in prayer a few minutes before the Feb. 11 public hearing in Penn Township.

“Please, God, give us all the strength and knowledge to make the proper decision for this township,” said Meyers, a 57-year-old township resident who recently retired after 30 years of construction work, which included laying pipeline for Marcellus Shale gas.

Most of the 50 or so people there, including suit-clad drilling representatives, bowed their heads. A collective “amen” hummed across the room.

Minutes later, the zoning board began listening to testimony regarding a hotly contested permit for a shale gas well pad.

Residents of Penn Township listen to testimony at a zoning board hearing on January 14 for one of Apex’s proposed well pads. If the zoning board approves the permit, it will be only the second permit granted in Penn Township for fracking. (Photo by Natasha Khan / PublicSource)

Residents of Penn Township listen to testimony at a zoning board hearing on January 14 for one of Apex’s proposed well pads. If the zoning board approves the permit, it will be only the second permit granted in Penn Township for fracking. (Photo by Natasha Khan / PublicSource)Since the community began changing its zoning laws in late 2014, the pad, if approved, would be only the second shale gas site in Penn Township – a rural-residential suburb about 20 miles east of Pittsburgh in Westmoreland County.

Penn Township hosts a mix of cookie-cutter single family homes in subdivisions and sprawling farms – some of which have been in families for generations. You can get away from city lights out here. Find a nice home and good school districts among picturesque rural scenery.

But not for long, some fear.

It’s been nearly a decade since the shale industry planted roots in Pennsylvania, and this community is just experiencing its first shale development.

It’s this mix of suburbia-meets-rural landscape that’s at the heart of the drilling debate in Penn Township: Many residents who live in residential areas don’t want drilling near their homes – fearful of what the activity could mean for their health, property values and way of life.

Other residents want to lease their land to drillers.

This is not the first community to experience shale drilling, and it won’t be the last. But its exposure to the tumult of first-time drilling and the controversies it brings provides a window into what it’s like for people on all sides of the debate.

Since a 2013 Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruling, several Southwestern Pennsylvania communities have ended up meeting in local government buildings – like Penn Township’s municipal complex tucked behind Fox’s Pizza Den in Harrison City – sharply divided on where shale gas drillers should be allowed to frack wells.

The state’s highest court overturned key parts of Act 13, the state’s governing oil and gas law, and gave the power to local governments to control some aspects of shale drilling through zoning.

Penn Township’s zoning ordinance allows shale drilling across about half of the township, much of which is rural land. The ordinance is pending and could change, but it is in effect.

Just one well pad in and Penn Township officials, residents and the drillers are struggling under the change.

The public hearing is mostly filled with residents against the pad. Under township rules, residents who object can try to prove to the zoning board that the site would be harmful to the environment and their health and safety. Then, it could be a violation of the ordinance.

Two hours into the hearing, Meyers, who said he lives about 1,100 feet from the proposed site on Dutch Hollow Road, testified.

“It would be just devastating,” he said about having fracking so close to his house. “I’ve worked in this industry. …I have a great deal of knowledge of how much noise and pollution is emitted.”

He’s concerned about his water well. He’s heard stories about Pennsylvanians losing their wells when drilling goes awry. He and his wife, Nancy, moved here in 1990 for peace and quiet, Meyers said.

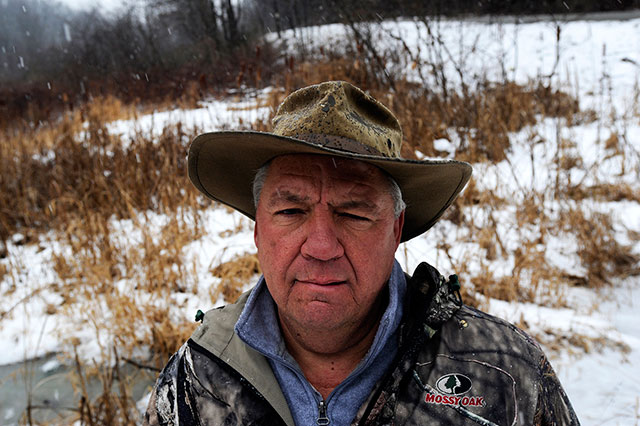

Gene Meyers worries that pollution from proposed natural gas wells would endanger Bushy Run, a stream, and the surrounding wetlands. (Photo by Connor Mulvaney / PublicSource)

Gene Meyers worries that pollution from proposed natural gas wells would endanger Bushy Run, a stream, and the surrounding wetlands. (Photo by Connor Mulvaney / PublicSource)

On cross examination, Jeffrey Wilhelm, a Reed Smith attorney representing Wexford-based Apex Energy Inc., the drilling company that wants to put seven more gas well pads in the township, peppered Meyers with questions about his experience in the gas industry.

Meyers said he had taken jobs hooking up about a dozen well pads to pipelines, mainly in Butler County.

“So you put unconventional wells in somebody else’s backyard, but you don’t want them in your backyard?” Wilhelm said.

The crowd wasn’t pleased. “Oh, come on …you jerk!” yelled one audience member. “Man, these guys are horrible!” jeered another.

Growing Pains

Up close, they looked like two giant furnaces. On a nearby hill, it almost looked like the trees were on fire. One person described the noise as, “like a helicopter hovering over our house.”

A couple of weeks before Halloween 2015, Apex was nearing completion on Penn Township’s first shale gas wells – on the Quest pad at Walton and Mellon roads in Jeannette, Pa., off Route 22.

(Map: Natasha Khan / PublicSource)Two wells had been fracked, and natural gas was being prepped for a pipeline that would shoot it into Pittsburgh homes.

(Map: Natasha Khan / PublicSource)Two wells had been fracked, and natural gas was being prepped for a pipeline that would shoot it into Pittsburgh homes.

About 650 feet away sits William Penn Care Center, a nursing home and senior living community. About a half-mile down the road is Walton Crossings Townhomes, a subdivision with carbon-copy houses stacked like dominos.

To pump the product into the pipeline, Apex first needed to burn off excess gas. To do this, the drillers decided to use incinerators, expensive and hauled from Canada, said Mark Rothenberg, Apex’s chief executive officer.

Flames shot on and off from the incinerators for about a week.

At this stage, another device called a flare is typically used, he said. But Apex officials chose incinerators because they burn “cleaner,” Rothenberg said.

A brochure on the Alberta Welltest incinerators Apex used says the device “converts 99.99 percent of methane to C02 and H20.” It also says, by contrast, flaring “will significantly increase the greenhouse gases emitted.”

Rothenberg said Apex’s policy is to ask themselves, “If we lived in that community, is this what we would want a company doing?”

On this issue, they concluded incinerators were the clear choice: “I don’t think we would want to flare. I think that would scare our neighbors,” he said.

It backfired. They were flooded with complaints.

Protect PT (Protect Penn-Trafford), a nonprofit citizens group against drilling near homes, tracked complaints via an online form.

“It is horrible and I am miserable. I moved out here because it WAS peaceful,” one person 1.8 miles from the well pad wrote on Oct. 12.

Others complained of residue on cars, a chemical taste in the air, sore throats and lack of sleep.

Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection officials visited to check the incinerators, Rothenberg said. The department found Apex had done nothing wrong.

Rothenberg said he felt like Apex had tried to decrease the impact, but they just got “beat up…as if we’re just evil people doing this intentionally to hurt people…And that’s the last thing we want.

“We probably would have been better off lighting a flare.”

Caught in the Middle

Alex Graziani looks tired as a work day nears an end in early December. The 45-year-old Penn Township manager has served as de facto liaison among residents, drillers and township officials.

It resembles a therapy session as he unloads for nearly two hours about the year since the township changed its zoning law. He’s drowning in emails, calls and questions from residents at township meetings.

“It just doesn’t wear out,” he said. “I mean, every day you’ve got people here, people there, wondering why you didn’t do this, why you don’t you do that.”

In late 2014, township commissioners agreed to a pending ordinance that created a “mineral extraction overlay,” which essentially allows drilling in most of the community’s agricultural and industrial zones.

To drill, gas companies seeking a permit must meet criteria – like placing a pad at least 600 feet from homes. Each permit must go through a public hearing at which drillers are asked to prove compliance.

Graziani said township officials tried to strike a balance between allowing landowners to lease their land and restricting drilling to areas with the least impact on residents.

“We’re just trying to make everybody happy as best we can within the law,” he said.

On one side, he’s got farmers telling him: “I’ll sell to ‘cookie-cutter subdivider X if I can’t get my gas.” Because the meager revenue these folks are making from “cows and hay and corn” isn’t cutting it, he explained.

“That’s the pattern of our township,” Graziani said, “farm loss, open space loss, to single-family, subdivision development.”

There are the gas companies that want to drill. Here, it’s Apex and Huntley & Huntley.

And then there are residents who feel shale gas drilling is threatening everything. Their property values. Their health. The environment.

“And they are getting to the heart of why people live in Penn Township to begin with. For that matter, suburbia in general,” Graziani said. He acknowledged that the commission’s decision could diminish the township’s “glow” as a bedroom community, but that they couldn’t put a stop to it based on a maybe.

It made sense to allow drilling in the township’s agricultural areas if gas companies can meet the protective criteria, Graziani said. Commissioners partly based the decision on the township’s population density (about 20,000 people inhabiting 30 square miles) and its history of resource extraction – coal mining and conventional gas drilling.

Township officials recognized Pennsylvania courts have been ambiguous about whether drilling can be limited to any one zoning district, such as industrial, Graziani said.

Other communities that have opened up more areas to shale drilling have sparked legal challenges from residents. A bitter fight is playing out in Butler County’s Middlesex Township, where residents and environmental groups are challenging an ordinance they said opened up too much land to drillers.

The challenge went to county court, where, in November, a judge upheld the ordinance. The residents and environmental groups have appealed the decision.

Threatening Suburbia

Gillian Graber lives with her husband and two young kids in a three-bedroom house on a woodsy boulevard in Trafford at the border of Penn Township.

But, as she describes it, it’s all the same community because the kids go to the same schools.

Gillian Graber is president of Protect PT, a nonprofit group focused on raising awareness about plans for natural gas drilling in Penn Township. (Photo by Connor Mulvaney / PublicSource)

Gillian Graber is president of Protect PT, a nonprofit group focused on raising awareness about plans for natural gas drilling in Penn Township. (Photo by Connor Mulvaney / PublicSource)

It’s Dec. 2, and her table is covered with colorful felt pirate swords and pink fairy wings she sews and sells at performances of The Nutcracker at the Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre.

The stay-at-home mom loves being close to the city for the culture, but moved in 2013 so her kids could attend the Penn-Trafford schools.

“You think…you’re doing the best thing for your family by moving here,” said 39-year-old Graber.

Then, Graber said, Apex announced plans to plunk a well pad about a half-mile from her house.

Graber started Protect PT in 2014 with the mission to keep drilling away from residential areas and make sure government officials “are doing what they should be doing.”

So far, they’re not, she said.

“The big shocker is that they could just overnight…say we’re going to take every rural area in Penn Township and make it available for unconventional gas development,” she said. Her group wants the township to limit drilling to industrial zones.

“We’re going to fight any well that’s in that mineral extraction overlay,” she said.

And they have. Members speak at almost every township meeting, and the group hired nonprofit law firm Fair Shake Environmental Legal Services to help oppose drilling permits.

The group has won some battles.

Last year, Protect PT went to court to appeal a decision by the township’s zoning board to grant Apex its first drilling permit.

The group said the approval violated the ordinance because Apex hadn’t turned in required air and water quality studies and an emergency response plan.

Township officials put a hold on the permit until the appeal made it through the Westmoreland County Court of Common Pleas, but Apex sued the township to start drilling immediately. The company said in court documents it was losing $70,000 every day it wasn’t allowed to drill.

The township lifted the hold, and Apex began drilling at the Quest well pad on June 16.

In the end, Graber’s group lifted its challenge when the township established that environmental studies and emergency plans would be required before permit approval.

A Landowner’s Rights

Gary Schuette lives about 10 miles east of Graber on Greer Lane in Penn Township. He and his wife, Susan, built their light gray colonial in 1999. Their acre of land is surrounded by four farms.

“Personally I would prefer them to put a gas well on there than have them sell off their property to a developer,” he told commissioners at an October township meeting.

Gary Schuette, pictured at his Penn Township home on Greer Lane, said he and most of his neighbors leased their gas rights to a drilling company last year. (Photo by Natasha Khan / PublicSource)

Gary Schuette, pictured at his Penn Township home on Greer Lane, said he and most of his neighbors leased their gas rights to a drilling company last year. (Photo by Natasha Khan / PublicSource)

Schuette and most of his neighbors leased to Huntley & Huntley last year, he said.

“There are too many people who are against it,” he said about why he spoke at the public meeting. “Somebody has to speak up and say, well, it can’t be all bad.”

Schuette said he agrees with the township’s ordinance.

“It’s good that they’re watching out for the people,” he said.

“I think our biggest thing is,” Susan Schuette said, “everybody talks about how they want us to be [energy] independent … Nobody wants it in their backyard … but somebody’s got to do it.

“All These Wells Are Going to Get Drilled”

Rothenberg – Apex’s 43-year-old CEO – seems more like the kind of guy you’d see on the ski slopes near his hometown of Denver than in a stuffy suit at a corporate board meeting.

His company is young, started in 2013, and small. Only five horizontal wells drilled so far.

“We started up Apex with really a desire to do things the way we feel is the right way,” he said.

Mark Rothenberg is CEO of Apex Energy, a drilling company based in Wexford, Pennsylvania. He said he believes all of the shale wells his company has proposed in Penn Township will get drilled despite opposition by residents. (Photo by Connor Mulvaney / PublicSource)

Mark Rothenberg is CEO of Apex Energy, a drilling company based in Wexford, Pennsylvania. He said he believes all of the shale wells his company has proposed in Penn Township will get drilled despite opposition by residents. (Photo by Connor Mulvaney / PublicSource)

To Rothenberg, when they were looking to invest in wells, that meant searching for communities that indicated they wanted industry to come in.

He said he saw nothing but green lights in preliminary talks with Penn Township officials; it was different in Murrysville, where it was clear they weren’t wanted.

“And so, there’s a little bit of frustration because we made tens of millions of dollars of investments and the first permit we try to put in there, ‘Oh, we have a pending ordinance,'” he said, bristling.

He didn’t expect to wind up in court, but now he suspects it’ll happen again.

“We believe all these wells are going to get drilled,” he said. “We think they are probably going to be some of the most economic wells in Southwest Pennsylvania to drill.”

“We believe all these wells are going to get drilled,” he said. “We think they are probably going to be some of the most economic wells in Southwest Pennsylvania to drill.”

If Apex doesn’t drill them, someone else will, Rothenberg said.

“So we’re going to do it. We believe we are the right company to do it.”

A grant from Arizona State University and The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation helped to fund this PublicSource project.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Our fundraising campaign is over, but we fell a bit short and still need your help. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.