Part of the Series

Struggle and Solidarity: Writing Toward Palestinian Liberation

In my role as a public school educator in Evanston, Illinois, I work in a community of learners with intimate ties to what today is called Israel and Palestine. There, I have struggled, alongside students and colleagues, with how to cultivate honest, ethical and just learning environments to understand and address what is happening in Gaza.

The schools in Evanston — a suburban city to the north of Chicago — serve many Jewish students as well as students who are immigrants and refugees from countries in the Middle East and elsewhere that have been acutely affected by the violence of U.S. militarism.

With the palpable threat of being silenced by Zionist-leaning individuals, community organizers and interest groups, and with the possibility of being labeled antisemitic by those who disingenuously and strategically conflate any criticism of the Israeli government or military with “antisemitism,” educators and learners like me are struggling to cultivate generative space to acknowledge and understand what South Africa has charged Israel with committing and what the International Court of Justice provisionally ordered Israel in preventing: a genocide.

In less than four months, over 26,000 Palestinians, mostly women and children, have been killed through unrelenting military aggression led by Israel, supported by the United States and European nations.

Even in the face of this mass death, however, the prevalence of Zionist ideology within national politics, media outlets and local community institutions alike has made it hard for those of us who are seeking to understand Palestine, Palestinian history and Palestinian humanity to speak up.

Despite that threat, educators across the country are refusing to be silenced. Just as we strive to teach our students about the vast suffering and violence that is also occurring in other parts of the world like the Congo, Sudan and Nagorno-Karabakh, we are striving to open discussions about the ongoing genocide in Gaza.

In recognizing this struggle, educators should and do have the ability to build humanizing learning environments that promote understanding about Palestine, Palestinian history and Palestinian lives in ways that disrupt the violent erasures and oppressive realities that Palestinians are experiencing in real time.

Here, I will offer two strategies to educators, facilitators and conveners seeking to engage in just teaching and learning about Palestine, actions that I have employed in my experience as an educator and scholar of human learning.

Strategy 1): When possible, build opportunities to share stories through multiple perspectives.

Stories are central to how we learn — and as a history teacher, I’ve tried to use stories, like my own, as a pedagogical practice. Not only are you able to model what learning and understanding can look like through your storytelling, you can also center multiple perspectives within these stories. I’ve often used storytelling as a vehicle in my own teaching and learning about Palestine.

Evanston Township High School (ETHS), a school with nearly 3,700 students, welcomes a multitude of racial, ethnic, gender, religious, socioeconomic and linguistic identities, among many others. During the 2014-2015 school year, my first period U.S. history class was memorable and dynamic because it brought together a significant number of the school’s third-year multilingual learners, several of whom I learned were refugees from Iraq. They came to Evanston as a result of Western militarism in the most recent Iraq War. Through divergent paths, they and their families made their way to the United States, to this diverse suburb just north of Chicago.

I, too, had a unique path to Evanston, growing up as a product of Philadelphia public schools, then as a first-generation college graduate attending Northwestern University. What I never anticipated — especially so early in my career as an educator — was that my story would be so inextricably linked to that of my students, particularly my students from Iraq.

My dad is a retired military veteran and while I was in high school, he served a tour in Iraq. As I tried to make sense of the actions the United States was taking there, all I knew was that my loving dad, who always put his family first, was doing his job so that he could take care of us. At that time, my mom was raising three Black boys while never knowing if her husband would come home from a fight he didn’t choose, a fear I too shared. To this day, I never asked my dad what his experience was like, but I know that it was traumatic not just for him and other soldiers, but for Iraqis as well. Shortly before I graduated from high school, he did return, albeit with PTSD and other ailments.

What I realized when I met my students, particularly those from Iraq, is that our stories were all tied together, especially around the traumas of violence. As a teacher of U.S. history, I felt a moral and ethical responsibility to cultivate an honest and truthful learning environment to better understand our shared histories. I was able to become an educator due to my dad’s career as an Army Reservist, which was directly connected to my family’s stability and livelihood. Unfortunately, my family’s stability and future was also predicated on violence that destabilized Iraq leaving 1 in 25 Iraqis displaced, several of whom ended up in my classroom, thousands of miles away from a place they called home. This is a story I shared with my students.

The relationship between my story and the stories of my Iraqi students who were refugees provided space for many in that first period class to understand one another. During our themed unit on U.S. conflicts, I shared parts of that story with my students, especially as I learned the stories about how my Iraqi students, who were energetic, charismatic and driven, fled to United States. At the end of the year, a student raised in Evanston — who later became an educator — reflected about how powerful it was to learn from and with multilingual learners, specifically through the stories shared between him and the Iraqi students.

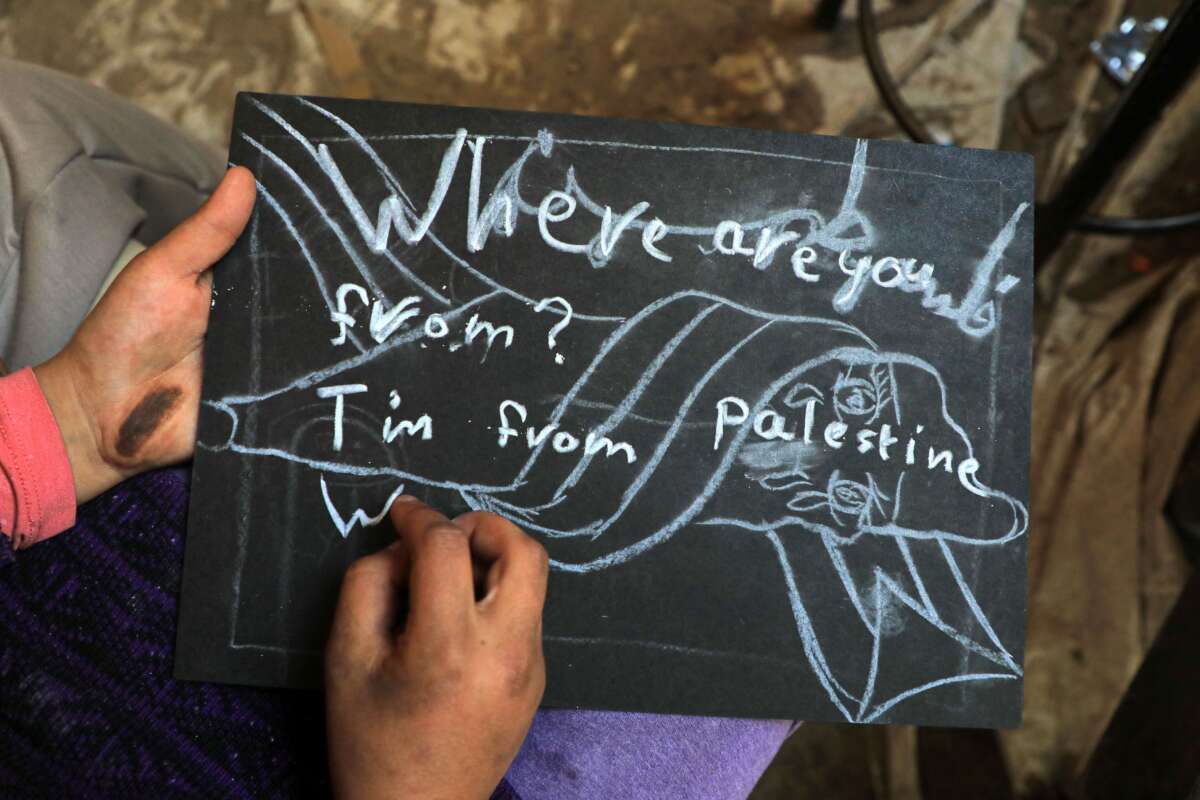

Bringing stories into our learning environments involves reflection, intentionality, relational trust and ethics of care. Regardless of course content or level, I model the types of storytelling practices I wish to see embodied in our relations with one another by sharing a bit about who I am, my identities and my purpose as an educator, and then by inviting learners to do the same with one another in small groups and in pairs. These consensual invitations to hold our individual and collective histories validates them in learning communities, providing opportunities for learners in the space to steward these stories and share them appropriately and generatively with others.

Today, I realize that this story offers context for why learning about Palestine is important in linking our humanity together. Teaching and learning about the Iraq War provided my class with an opportunity to confront our own proximities to U.S. militarism and violence while centering our shared humanity. What parallels my story on a much larger scale is that Cook County, Illinois, has at different points in time, both been home to the largest number of Holocaust survivors outside of Jerusalem and the largest population of Palestinians in the United States. There’s a real opportunity here to open space for deeper learning and understanding. But learning through storytelling, especially through multiple perspectives, is endangered when officials repeatedly attempt to ban discussions of certain topics and ideologies.

Strategy 2): As educators, facilitators and conveners, we are not alone. Consider, curate and leverage your resources. Connect to what is available to you from your text selection, to local laws and national coalitions to engage in justice-oriented learning.

In 2019, I was questioned by several administrators due to how I’ve taught about Palestine. My use of a personally annotated copy of Angela Davis’s Freedom Is a Constant Struggle to talk about prison abolition in a sociology of class, gender and race course upset a family who brought their concerns neither to me nor to my direct supervisor, but to my supervisor’s direct supervisor. Without having had the opportunity to engage the student or their family, a dialogue I believe was necessary for deepening understanding, I was encouraged not to use that version of the book with my personal annotations. I was told that my acknowledgments of Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions (BDS) in annotations were considered antisemitic in some Zionist communities.

Instead of accepting the limits placed before me, I found other avenues to inspire learning in discussing the ties between abolition and Palestinian resistance and resilience. Similar conversations about the connections between abolition movements and Palestine were presented in Charlene Carruthers’s Unapologetic: A Black, Queer, and Feminist Mandate for Radical Movements, a text I excerpted to replace Davis’s work. As educators seeking to disrupt the status quo, we sometimes have to move beyond the limitations of institutions in the name of justice and equity.

In that spirit, it is important to know and understand the laws governing our work as teachers and learners. Illinois is one of 21 states that has legislation requiring educators to teach about the Holocaust and other genocides. In 1990, Illinois became the first state in the country to mandate each public elementary school and high school to include in its curriculum a study of Holocaust history. In 2005, it expanded the mandate to include other cases of genocide. Given this statutory perspective, there should be no issues building space to talk about the atrocities that have been and continue to be committed against Palestinians in Gaza and the West Bank. Today, educators nationally and internationally are calling for a ceasefire and are developing teach-ins about Palestinian history and humanity. There is an ever-growing set of resources and communities of educators who are working together, across classrooms, district lines, state borders and even international boundaries to build capacity to engage in justice-oriented teaching and learning about Palestine. My personal favorites include Teach Palestine, Rethinking Schools on Palestine and Haymarket Books’ selection on Palestine.

Towards the Worlds We Want to Build

As an educator and learner, it is important to acknowledge the political nature of our work and to consider the worlds we want to build. What does it look like to create possibilities for learning such that we see one another’s humanity? How will we engage young people here in understanding what is happening in Gaza to young people there such that we understand how our actions impact one another’s lived experiences? Our worlds, although they seem miles apart, are interconnected. Our traumas, although they seem miles apart, are interconnected. Our joys, although they seem miles apart, are interconnected. Our futures, although they seem miles apart, are interconnected. Silence constitutes harm and I see my own histories as a queer Black American in the Palestinian struggle for liberation. Telling our stories is key to liberation from these struggles. Let’s ensure that we continue to tell them so that the next generations can avoid the violence we continue to experience.