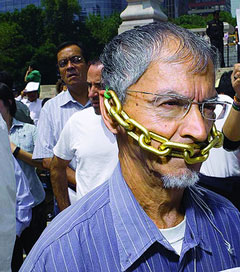

Mexico City – “I want to request the resignation of the Secretary (Minister) of Public Security. We want a message today from the president, showing that he did hear us,” said poet Javier Sicilia before a crowded square overflowing with demonstrators who participated in a four-day-long March for Peace with Justice and Dignity in Mexico.

Thousands of voices in the Zócalo, the main square in Mexico City, shouted “¡Fuera Calderón! ¡Fuera Calderón!” (Calderón out! Calderón out!).

By flinging the armed forces into the crackdown on drug trafficking cartels, President Felipe Calderón has only worsened the spiral of violence. Since January 2007, nearly 40,000 people have been killed in increasingly grisly drug-related murders, and growing numbers of people have been displaced, disappeared, mutilated, widowed or orphaned, although no one can say exactly how many victims there are.

Sicilia calmed the crowds: “No more death, no more hate. We have come here to walk these streets with dignity and peace. Violence will only lead to more violence,” he said. Then he gave the authorities and political parties, whom he accused of being infiltrated by organised crime, his parting shot.

“We will no longer accept election results until the political parties cleanse their ranks of those who hide behind a mask of legality, but are in collusion with crime,” he said.

Sicilia, whose own son was murdered Mar. 28, and thousands of demonstrators arrived in the capital after a silent four-day march that covered a distance of 85 kilometres, to protest a war in which “Mexicans are killing Mexicans.”

IPS accompanied the march from its outset May 5 in the southern city of Cuernavaca, which has become another focus of impunity and social disintegration.

In towns and villages on the marchers' route, they received shows of support from local people, including food and symbolic items to give them strength on their journey.

Similar protests were held in 17 countries and 31 Mexican cities. The largest was in San Cristóbal de las Casas, in the southern state of Chiapas, where some 5,000 members of the left-wing Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) demonstrated in support of Sicilia's movement.

It was the first public appearance of the indigenous insurgent group in five years, ever since its leader, Subcomandante Marcos, led a convoy called “The Other Campaign” around the country in March 2006. Another Zapatista leader, Comandante David, read out a communiqué signed May 7 by Marcos, expressing solidarity with the innocent victims of the war on crime.

“We are here to tell these good people who are marching in silence that they are not alone. We hear the pain of their silence, just as earlier we heard the worthy rage of their words,” he read.

In the capital, Sicilia walked from the National University to the Zócalo, a march of over seven hours, together with dozens of bereaved people, many of them well-known, like Eduardo Gallo, who pursued and found the killers of his daughter, but many more who were plucking up the courage to protest the loss of their loved ones for the first time.

In the front line of marchers were Julián LeBarón, the leader of a Mormon community in the northern state of Chihuahua, whose brother Benjamín was murdered in 2009, and two Roman Catholic priests, Miguel Concha, a human rights activist, and Alejandro Solalinde, who has received threats for his work on behalf of Central American immigrants.

Behind the victims' relatives were social and small farmer organisations: the Policía Comunitaria (community police force) of the southwestern state of Guerrero and the farmers of collectively owned land in Michoacán, also a southwestern state, who have organised to defend themselves against drug traffickers. With them were the children of victims of forced disappearance during the “dirty war” of the 1960s and 1970s.

It was difficult to count the crowds that overflowed the streets on the marchers' route, but the turnout was massive. At one of the crossroads of the Eje Central, which traverses the capital city from south to north, the visible column of people went on for kilometres.

At the Zócalo, more than 70 people put their names down to use the microphone to address the rally, but only 30 were able to do so. Their appalling accounts spoke of women raped and murdered, immigrants shot by police, mothers in Durango (in the centre-north) and Coahuila (north) demanding DNA tests on bodies found in recently-discovered mass graves, to try to identify their missing daughters.

In every case, the inoperativeness of the authorities was glaringly obvious.

The father of Adriana Morlett, a student who disappeared Sept. 6, 2010, moved everyone present with his heartfelt appeal to the authorities: “Get to work! DO something!” he cried out passionately.

Silvia Escalera, the mother of a young woman who was kidnapped and murdered in 2007, appealed to kidnappers: “Please give back the living, please give back the dead, so that parents can be at peace.”

Olga Reyes, who lost six members of her family in the northern town of Ciudad Juárez, on the U.S. border, and Patricia Duarte, the mother of one of the children who died in a fire at a day care centre in Sonora, in the northwest, read out the names of the victims in notorious cases and, after each name, the entire crowd in the Zócalo replied “S/he should not have died!”

The women's voices broke and they could be heard sobbing as a proposal was presented for a social pact focused on getting to the bottom of the crimes that have racked the country.

The main demand is for a radical change from a “war strategy” to one of citizen security with respect for human rights, an economic policy that creates opportunities for the young, and a political reform to include the power to recall politicians before the end of their elected terms, citizen candidacies and the democratisation of the media.

The pact, which sets deadlines for government and legislative action on each of its points, will be signed by civil society organisations Jun. 10 in Ciudad Juárez, “the most visible face of national ruination,” Sicilia said.

On Sunday night, the interior ministry, headed by José Francisco Blake Mora, issued a statement saying the armed forces are not the cause of the violence – seen as a feeble response in comparison to the force of the demands expressed and the community bonds created between the victims' relatives who met on the march.

“I feel happy and supported. The placard (with a photo of his son) was heavy, but my pain was even harder to bear, and the result is so much greater than I expected,” Melchor Flores, the father of a young man who worked as a living statue and was allegedly killed by police in the northern state of Nuevo León, told IPS.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.