Part of the Series

The Road to Abolition

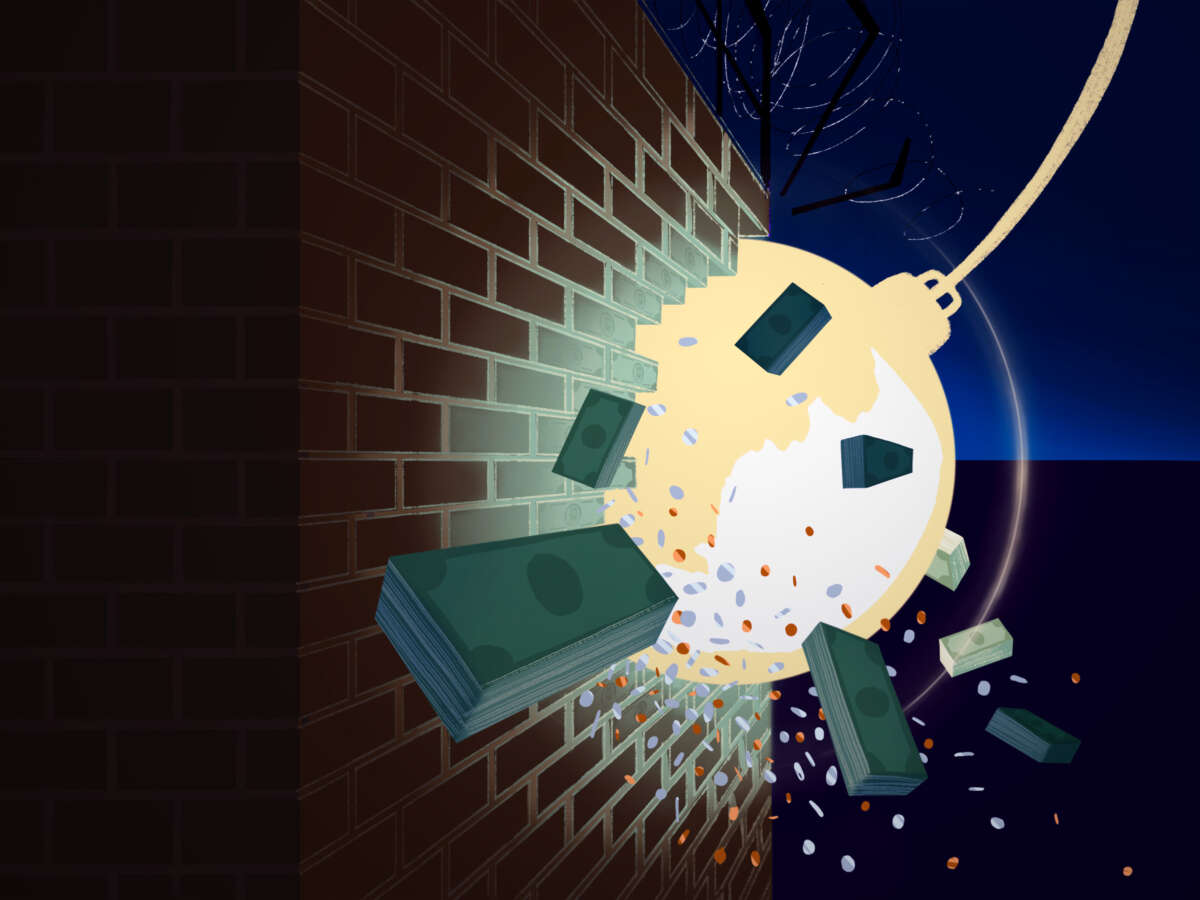

What would you do with 900 million dollars?

People incarcerated at two maximum-security prisons in Illinois are brimming with ideas about how to spend that sum: Ending poverty via a guaranteed minimum income. Offering free public post-secondary education nationwide. Providing accessible, free and affirming mental health care for all. Creating programs to work with boys and men to end gender-based violence. Building nine sparkling new $100 million-dollar public high schools.

These suggestions came from people in classes at Illinois’s Stateville and Logan prisons, both of which were recently slated for closure and a whopping $900 million dollar rebuild (despite the 12,000 already vacant prison beds that exist in Illinois). As faculty members at public universities who also teach in these prisons, we asked our students what they would use that money for instead.

We choose to teach in prison because incarcerated people are valued members of our communities and working with them is part of our commitment to the people of Illinois. Because of this work, we regularly witness deadly prison conditions: toxic water, collapsing ceilings, unrelenting heat and cold, and poisonous mold. Michael Broadway, a member of our inside community at Stateville Prison, died in late June 2024, likely from respiratory complications incurred from excessive heat (a routinely lethal condition in prisons across the U.S.).

We applaud the closures of these prisons.

Yet, Illinois and other states are at a familiar crossroads. Many prisons across the country — specifically enormous aging penitentiaries from Sing Sing in New York to Stateville in Illinois — are decrepit and toxic. Those who want to build more prisons cite poor conditions and the need for newer prisons to facilitate programing and “increased safety” as the official rationales for new construction.

But this moment requires intervention and organizing, not prison expansion. The futures we are building do not involve life on either side of a prison wall.

A Familiar Crossroads

Between 1970 and 2000, the United States engaged in a prison construction binge, building approximately 1,000 prisons. Prison populations soared during this time period, not because people were more dangerous, but as a direct result of policy and ideological shifts across the criminal legal system: longer sentences, enhanced penalties, an expanding net of criminalization, and more. All of these shifts targeted and criminalized those already engineered to be vulnerable — including Black people, queer people and people with disabilities.

This moment requires intervention and organizing, not prison expansion. The futures we are building do not involve life on either side of a prison wall.

Over the last decade across the U.S., prison populations have dipped, often marginally, with the most significant decrease occurring during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Why the decline? Some mainstream news outlets suggest an increased awareness of the problem of mass incarceration, or empty state coffers and the proliferation of other, cheaper forms of enclosure and stigmatization including electronic monitoring and public registries. Yet abolitionist demands have also penetrated and impacted public consciousness: Decarceration is an imperative for those invested in racial, economic and gender justice. Our movements continue to achieve wins, and also to push communities to pull apart incarceration and policing from community wellbeing to ask what safety really looks and feels like.

Over the last two decades, states have been slowly and quietly shuttering prisons — a tangible abolitionist win. New York may close five prisons in the next fiscal year. In California, Governor Gavin Newsom has shuttered four prisons and is considering more closures. In 2023, Washington state closed a prison for the first time in a decade.

Yet, while the U.S. has closed more prisons than it has opened since 2000, and despite widespread abolitionist organizing, new prison plans continue to surface. Illinois’s costly rebuilding plans are not unique: the Republican-led states of Alabama, Georgia, Indiana and Nebraska are all in some stage of mega-prison construction. Specifically, new prisons for women are once again on the table, in South Dakota, North Dakota, Massachusetts, Louisiana, New Jersey and Vermont. (We argue that abolitionist organizing defeated the grotesquely oxymoronic so-called feminist jail in New York City — the site is now slated for affordable housing units.)

Even if the dip in incarcerated populations is only marginal (for now!), we continue to organize to reject prison expansion. And we are not alone. From religious communities to the construction industry, people question and reject incarceration as the future to build.

Decarcerate People With Life Sentences

One of the arguments behind prison construction and expansion is that “better” prisons are needed to incarcerate the many people serving life sentences.

We have relationships with people in Illinois prisons who are serving these life sentences — 67 percent of people serving life or de facto life sentences in Illinois are Black. Each one of them is someone’s sister, father, cousin, lover, auntie. Most have already served decades behind bars. With no parole system, and truth in sentencing requiring people to serve almost or all of their full sentence, Illinois has condemned them to death by incarceration. Elderly release bills, which could let people out who have served 25 years, and medical and compassionate release legislation are stalled. Petitioning the governor for clemency or commutation is the only pathway for release for most people at Logan and Stateville, and those who are eligible wait years for any response — usually negative — to a process investigative journalists recently described as “arbitrary and opaque.”

And Illinois is hardly an outlier. Across the U.S., the population serving life has increased fivefold since 1984. Approximately one in every seven people in prison in the U.S. is serving a de facto life sentence. One in every 15 women in prison has a life sentence. Draconian policies — including sentence enhancements, overcharging and over sentencing — and parole restrictions keep people behind bars endlessly. Serving life does not create opportunities for people to repair harm they may have done, to support their children, or to contribute to their communities. Attempting to disappear people does nothing to change the environments or conditions that made harm possible in the first place.

From religious communities to the construction industry, people question and reject incarceration as the future to build.

Locking people up indefinitely is also not an effective public safety strategy, as sentences are not a deterrent. As feminist scholars with decades of experience working to end gender-based violence, we know that one of the riskiest places for a woman and her children is still her own home. Harsher sentences and new mega-prisons do not help prevent or end gender and sexual based violence; we cannot incarcerate or prison-build our way out of this problem.

Expanding policing and punishment under the guise of creating safe communities is an old and patently false myth. The United States already holds the global record: We have the largest prison population in the world. Illinois locks up more people than France, the United Kingdom, Canada and Portugal combined.

Yet, we are not any safer.

The nation must commit to decarceration — including for those with long sentences. Not only do these long sentences not build safer communities, deter violence, hold people accountable for harms they may have committed, or change the conditions that made violence possible — these endless sentences justify expanding carceral budgets and new prison construction.

Don’t Be Fooled by Rehabilitation Rhetoric

“Rehabilitation” is the buzzword behind some of the pushes to rebuild prisons. With coding classes, college access and culinary training, activists pushed California Governor Newsom to transform San Quentin Prison — the site of hunger strikes, endless solitary confinement, and the state’s electric chair — into a “rehabilitation campus.” Meanwhile, the need to deliver gender-specific, trauma-informed services justifies proposed new prisons for women in multiple states. Degree and credit earning educational programs are expanding in some prisons across the country, as Pell grants have been reinstated for people in prisons, and some carceral budgets forefront “education and vocation facilities.”

Yes, people inside prison merit and require access to necessary and affirming services — education, job training, health care — but we need to keep our eyes on the prize. Our goal is not to inject billions into carceral systems in the name of programs or services.

Pouring money into a few boutique programs serves to whitewash core facts. Many incarcerated people were actively robbed of these public goods and services in their home communities. Incarceration is not a public safety strategy: locking people up does not make our neighborhoods safer. Despite decades of “reform,” prisons are still sites of endemic harm — gender and sexual violence, medical neglect, racism. And a prison can and does weaponize every facet of life inside.

Even with college programs — a prison is a prison is a prison.

We don’t need deep-pocket investments into so-called “programming prisons” when these same services or free programs are denied to people in the world outside of prisons. (Students in the free world face mounting tuition costs and shrinking access. Student debt, which has more than doubled in the last decade, is now one of the largest forms of consumer borrowing in the U.S., exceeded only by mortgage debt.)

Illinois locks up more people than France, the United Kingdom, Canada and Portugal combined.

People need and deserve free classes — coding, college, culinary, and more — in our communities. Why are public dollars always so readily available for prisons, but the state coffers are closed for other public services, such as education? In Illinois, state contributions to public higher education declined 50 percent since 2002. Illinois prison budgets inflated 22 percent between 2011 and 2022 even as the incarcerated population declined.

Build the Futures We Deserve

May and June are full of graduation ceremonies across the country. Our brilliant and joyous students are generally the first in their family to attend any form of post-secondary education. Most work full time, many are parents. Some have been incarcerated, or have loved ones in our state’s prison system. Most struggled through significant hurdles like migration, health crises, caregiving, poverty and a global pandemic, to learn and to earn their degrees.

Why are public dollars always so readily available for prisons, but the state coffers are closed for other public services, such as education?

Our years inside Illinois prisons, and our years working with equally thoughtful and curious not currently incarcerated students at our public universities, lead us to champion these prison closures, while also demanding people’s release and pushing back on the billion-dollar rebuild plan.

Like our students inside and outside prisons, we can think of so many uses for almost a billion dollars. Why not open two new free public universities or community centers full of vibrant and free services and programs? Why is Illinois always hiring prison guards (salary for a correctional officer trainee is $53,820 per year plus excellent benefits, and the minimum qualifications are: 18 years of age; valid driver’s license; high school diploma or GED certificate; U.S. citizenship or authorized alien with proof of a permanent resident card; ability to speak, read and write English) but not public school music teachers? Why is policing among the hottest job markets on a university campus, while we struggle amidst a tidal wave of unmet mental health needs?

When we organize to close prisons and jails we do achieve wins. Our campaigns and organizing build powerful coalitions that highlight how prisons can be repurposed to be life affirming — community gardens, farms, spaces for those unhoused, museums, and so much more.

Our communities merit and require flourishing futures. When we learned about the almost 1 billion dollar plan to close and rebuild Stateville and Logan prisons, we asked ourselves and all our students, how could $900 million build the communities we need? Everyone should be asking this question, now.

Our most important fundraising appeal of the year

December is the most critical time of year for Truthout, because our nonprofit news is funded almost entirely by individual donations from readers like you. So before you navigate away, we ask that you take just a second to support Truthout with a tax-deductible donation.

This year is a little different. We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. 2025 was a year of frightening censorship, news industry corporate consolidation, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We’ve set an ambitious target for our year-end campaign — a goal of $250,000 to keep up our fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout before December 31. If you have the means, please dig deep.