Part of the Series

The Road to Abolition

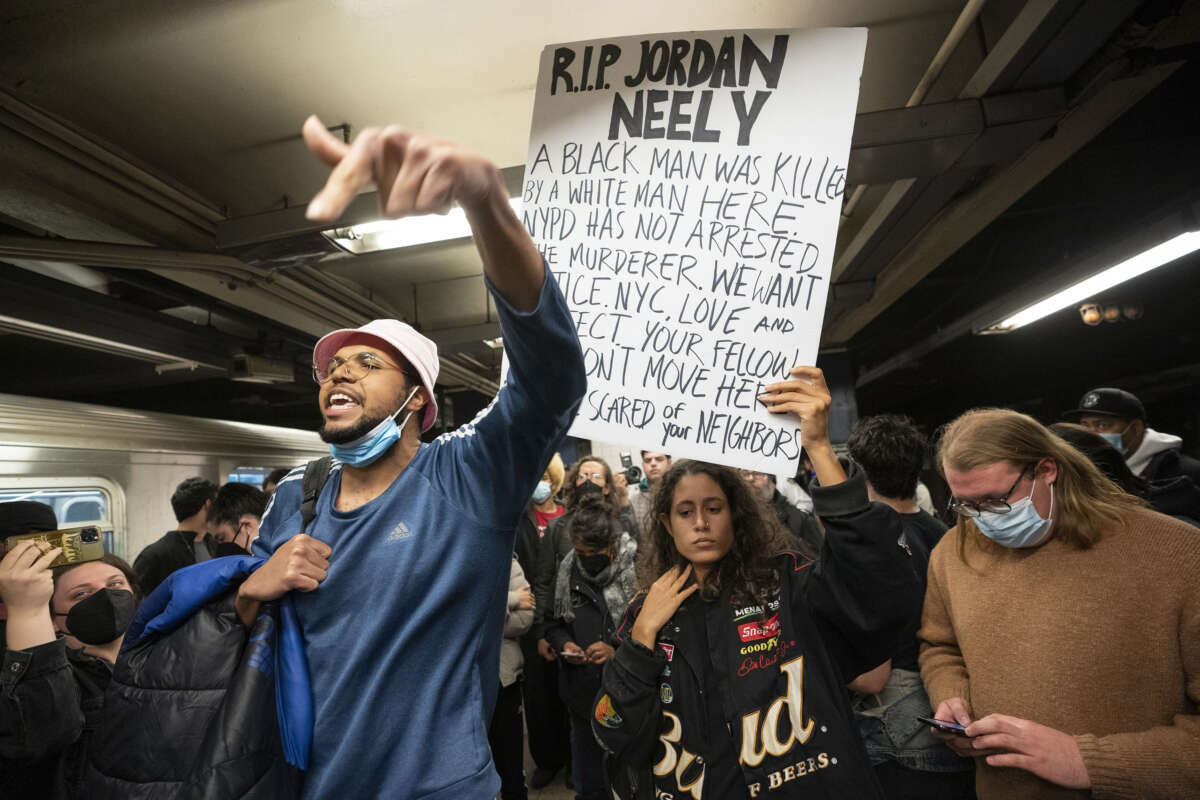

The horrific choking murder of 30-year-old Jordan Neely by a white MTA rider on May 1, 2023, in the New York City subway sparked mass outrage, with demonstrators converging on subway stations while cops brought “force and chaos” to a vigil in his memory. The murder has put a renewed spotlight on carceral logics of the state that assume the disposability of Black, poor and unhoused people — in particular those said to be in “mental health crisis.”

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul’s response to Neely’s killing deflects from the white supremacist violence and ongoing lack of accountability for the killer, and instead medicalizes Neely’s death: “People who are homeless in our subways, many of them in the throes of mental health episodes, and that’s what I believe were some of the factors involved here. There’s consequences for behavior.”

And in the wake of the homicide, Mayor Eric Adams — whose rhetoric and policies were already being criticized as demonizing unhoused and disabled people on the MTA — highlighted his mental health involuntary removals policy, which forces psychiatric care on unhoused New Yorkers like Neely who “appear mentally ill.”

New York is far from alone in this approach. In a setback for the already precarious rights of these marginalized and oppressed vulnerable groups, cities and states across the U.S. are making it easier for cops and medical authorities to disappear mad, disabled and unhoused people from the streets.

Policies such as California Gov. Gavin Newsom’s CARE Court and numerous “anti-camping” ordinances are reinterpreting existing legal protections to allow for the removal and detention of people who are unhoused and deemed mentally ill, under threat of involuntary commitment or even conservatorship.

While these policies are put forth as a “compassionate” response to houselessness, they offer little to no permanent supportive housing or other material supports.

Following Adams’s November 29, 2022, announcement, activists rallied with signs saying “Mayor Adams: Roll Back Your Dangerous Mental Health Plan” and “NYPD does not equal care.” Disability Rights California and numerous other organizations launched a legal challenge to CARE Court, alleging that it violates California’s constitution. Advocates in New York mounted a similar challenge to the Adams administration policy. Both legal challenges were rejected; in the case of CARE Court in April 2023, the rejection occurred with no explanation.

While recent efforts to expand the state’s powers to compel psychiatric care and institutionalization are hailed as a “paradigm-shift,” they are nothing new. As Beth Haroules from the New York Civil Liberties Union testified, “The Mayor’s attempt to police away homelessness and sweep individuals out of sight is a page from the failed playbook of countless Mayoral administrations before his.” In the late 1980s, Mayor Ed Koch led an almost identical initiative. This rising turn to past practices is deeply worrying, not only because of its violent consequences but also because these practices of institutionalization and forced treatment had been fiercely resisted since their inception.

Hospitals are dangerously framed as a “kinder” alternative to jails, prisons and houselessness, leading to calls to “bring back the asylum.”

Deinstitutionalization in mental health began in the 1960s and became a major policy in almost every state, if unevenly applied. The closure of psychiatric facilities occurred because people and movements pushed for it (including disability and mental health rights advocates, activist lawyers, mad and disabled self-advocates, and their families). It also happened because of racist neoliberal policies that led to budget cuts in all service/welfare sectors, and little to no funding for affordable and accessible housing and social services, while the budgets for corrections, policing and punishment (mostly of poor people of color) skyrocketed.

Instead of learning from the movement for deinstitutionalization, there are now renewed calls for the exact opposite.

Deinstitutionalization and Reinstitutionalization

Deinstitutionalization is defined as the closure of psychiatric hospitals and large state institutions for disabled people, and the transition to community mental health, community living and home care. In Decarcerating Disability: Deinstitutionalization and Prison Abolition, Liat Ben-Moshe also defines it as a logic, a social movement. Deinstitutionalization as a noncoercive, non-carceral logic was based on the idea that no one should be segregated based on their disability and people should get the material and other support they need to live in the community with family and peers. It was about the abolition of social control and medicalization of disability/madness.

As the movement was gaining momentum, thousands of disabled people were being released from state institutions, but in most states, it was still relatively simple to get committed to a psychiatric facility for life, with little semblance of due process. The reigning legal principle of the time was parens patrie, which gave the state nearly unlimited powers to detain and confine those deemed mentally ill and unable to care for themselves.

During this time, a series of landmark legal cases, notably Lessard v. Schmidt (1972) and O’Connor v. Donaldson (1975), ushered in the strictest ever due process protections for people facing involuntary psychiatric commitment, resulting in a new legal standard. The state would now have to prove a risk of imminent danger to self or others in order to justify individuals’ deprivation of liberty.

There was almost immediate pushback from medical and family caregiver communities. In 1973, psychiatrist Darrold Treffert published an article in the American Journal of Psychiatry entitled “Dying with Their Rights On.” Treffert referenced a number of tragic deaths of disabled people deemed not committable under the new laws. He argued that had they been eligible, these tragedies would not have occurred. These anecdotal examples were used as pretext for rolling back the clock to the previous “need for care” standard.

This destructive rhetorical strategy continues to this day. Sixty years after deinstitutionalization began, politicians and pundits across the political spectrum falsely declare it to be a failure — when in reality, the vision has yet to be funded or realized.

And in a narrative that has gained traction among liberals, deinstitutionalization is blamed for houselessness and mass incarceration, expressed in the trope “prisons are the new asylums.” Hospitals are dangerously framed as a “kinder” alternative to jails, prisons and houselessness, leading to calls to “bring back the asylum.” Pro-force activists falsely declare that the Housing First program, the gold standard for permanent supportive housing, has “failed” — in their view, yet another reason to reopen the institutions.

They seize on mass shootings, subway pushing incidents, and other horrific but extremely rare acts of violence committed by disabled people — who are far more likely to be at the receiving end of violence — to call for more force in the name of “treatment before tragedy.” After the Sandy Hook shooting in 2013, former Rep. Tim Murphy (R-Pennsylvania) led a multiyear legislative effort to scapegoat “mentally ill” people for mass shootings and to expand involuntary and restrictive care federally. The bill never passed in Congress, but elements were folded into the 21st Century Cures Act.

Murphy was influenced by the work of E. Fuller Torrey, psychiatrist and founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center (TAC), a think tank advocating for involuntary outpatient commitment, euphemistically rebranded as Assisted Outpatient Treatment (AOT). Now on the books, in some form, in 47 states, these programs compel individuals to comply with court ordered “community treatment,” under threat of inpatient commitment for noncompliance.

Brian Stettin, longtime policy director at TAC, helped to write the AOT laws in New York in 1999. In July 2022, he became the Adams administration’s senior adviser for severe mental illness, and authored the city’s psychiatric crisis care agenda, which heavily emphasizes the expanded use of AOT. Critics point out that AOT orders have been shown to be disproportionately enforced on Black and Brown people.

Today, we can be said to be living in a rising era of carceral sanism. Sanism is oppression faced due to the imperative to be sane, rational and non- mad/crazy/mentally ill/psychiatrically disabled. In Decarcerating Disability, Liat defines carceral sanism as “forms of carcerality that contribute to the oppression of mad or ‘mentally ill’ populations under the guise of treatment.”

Fifty Years of Resistance to Psychiatric Force and Oppression

As long as there have been efforts to limit or negate the rights, legal protections and liberation of the “mentally ill,” there has been fierce resistance. There were always strands of psychiatric abolition in the deinstitutionalization movement, whether desiring the abolition of psychiatry, psychiatry as a field of medicine or the coercive features of institutionalization and forced treatment. In the 1970s, anti-psychiatry professionals led by George Alexander, Thomas Szasz and Erving Goffman formed an organization called the American Association for the Abolition of Involuntary Mental Hospitalization. Of course, this abolitionary strand is not the one that won or is remembered, because of the sustained smear campaigns declaring the “failure” of deinstitutionalization.

The earliest mental patients’ liberation movements that arose in the 1970s also called for a ban on all forced psychiatric interventions. For decades, activists identifying as ex-prisoners and psychiatric survivors have protested these policies, raising banners with slogans like “Housing not Haldol” and “No Forced Treatment Ever.” In their view, the term “forced treatment” is itself an oxymoron, because if it’s forced, it isn’t treatment — it’s violence.

The prison and the asylum are two sides of a carceral coin.

For a half century, psychiatric survivors and allies have not only sought to abolish forced psychiatry, but also to redefine care in a liberatory way. Madness Network News was a groundbreaking anti-psychiatry journal that emerged in 1972. The journal, founded and run by psychiatric survivors, provided a platform for mad people to speak out about abuses within psychiatric institutions. Through articles, poetry and personal narratives, Madness Network News challenged the dominant biomedical narrative of mental illness and called for a new paradigm of collective care and survivor-led mutual aid.

In the mid-2000s, global psychiatric survivor activists were instrumental in ensuring that the UN international human rights treaty, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), contained provisions prohibiting all forms of nonconsensual intervention. Article 14 provides for a ban on detention and confinement on the basis of impairment or disability. Issues around legal capacity are addressed in Article 12; instead of involuntarily detaining people presumed to lack the capacity to consent to treatment, they should receive support in exercising their legal capacity, using tools such as supported decision-making that are meant to explicitly honor choice and agency. The CRPD has yet to be ratified by the U.S., an unsurprising rejection of a human rights approach to mental health and disability.

In recent years, neurodivergent, disability justice and mad pride movements have brought a resurgence to calls to end institutionalization and imprisonment. Mad pride refers to the idea that individuals with psychiatric histories should be proud of their identity and collectivize to dismantle the discrimination and sanism associated with the biomedical model.

These activists fight for change based on the values of choice, autonomy, trauma responsiveness and community-based peer support. As an alternative to psychiatric hospitals and other places of confinement, they’ve innovated peer-to-peer outreach programs and peer respite, a voluntary, short-term, home-like environment in the community where people experiencing crisis can access 24/7 peer support. And they’ve organized to free comrades trapped in the system; MindFreedom’s Shield Campaign is just one example. Shield members can request an action alert to be sent to the public if they’re experiencing or at risk of coerced psychiatry. In one instance, the community came together to help a member fight a court order for forced electroshock. These communities know that rights have always been precarious, hard-won and fought-for.

Psychiatric Abolition: The Future of Resistance to Carceral Sanism

Disillusioned with the pendulum-swinging represented by “mental health reform” efforts of the past half-century, momentum builds for psychiatric abolition, echoing the radical roots of mental patients’ liberation struggles in the 1970s. Psychiatric abolition does not seek to take away access to supports or medications that people want and need, but to renew the intersectional fight against all sites of carceral “care,” coercion and confinement.

Absorbing the lessons of the past in which the fight to stop psychiatric force was siloed as a single-issue struggle, organizers work in solidarity with movements for prison abolition, decarceration and disability justice. They argue that psychiatric intervention is not a solution to policing and imprisonment — rather, it is the problem, illuminating the connections between seemingly disparate sites of coercion and incarceration. Psychiatric institutionalization is not “like” prison; the prison and the asylum are two sides of a carceral coin.

Rejecting victim-blaming and coercive policy moves, the movement calls for approaches rooted in public health — housing justice, education, guaranteed income, peer-delivered crisis supports, and accessible, community-based forms of health care and mutual aid.

This movement includes organizations such as Black Emotional and Mental Health Collective, Call Blackline, Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets, Cambridge HEART, Depressed While Black, Fireweed Collective, Interrupting Criminalization, Kiva Centers, Mental Health First Oakland, Peer Support Space, Project LETS, Promise Resource Network, Trans Lifeline, Weglaufhaus Villa Stöckle “Runaway-House”, Wisconsin Milkweed Alliance, Wildflower Alliance and Yarrow Collective.

Aligned with disability justice principles centering the leadership of most impacted people, the movement uplifts the narratives, perspectives and solutions proposed by those who have been directly harmed by carceral sanism and force. As Róisín with the Campaign for Psychiatric Abolition wrote: “The only chance we have at psychiatric abolition lies in the hands of the people who cannot afford to live another second under psychiatry, with the names and faces of our friends lost to psychiatry emblazoned in our minds.”