Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

Tayz Enriquez, a senior at a high school in Greeley, Colorado, convinced herself that the day after the 2016 election would be a normal one. But that morning, as she walked through the school’s hallways, she heard students asking others, “You’re still here?”

“To be fair, I’m not sure if they were joking,” she told Truthout. “But it’s still not OK to say.” None of the comments were directed at Enriquez, whose parents are originally from Mexico, but she felt the tension in the air. Then came the last class of the day. Enriquez was already in her seat when another student, a white boy, walked in and loudly said, “Trump 2016! Build the wall!”

Enriquez chose to ignore him. The teacher, however, did not. “She told him that his comment could offend other people,” Enriquez recalled. But the boy, egged on by his friend, refused to stop, arguing that the teacher was infringing on his first amendment right to free speech. Enriquez, who had previously discussed politics with the boy and never had a problem with him, intervened, reminding him that the school was diverse and his words might offend people. “I’ve known you for two years. I can’t believe you’re acting this way,” she recalled saying to him.

“Well, you can have fun on the other side of the wall,” he responded. He also told a Muslim classmate, “Go be somewhere else.” When the teacher sent him to the school counselor, he continued to yell, “Trump 2016! Build the wall!” as he walked down the hallway.

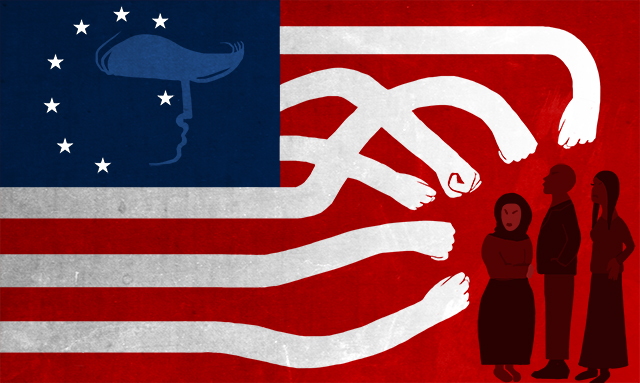

What happened to Enriquez was not an isolated incident. The election seems to have further emboldened students to taunt, intimidate and, in some cases, physically hurt their classmates. In the three days after the election, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) received more than 200 reports of hate-based harassment and intimidation. Of those, over 40 occurred in elementary, middle and high schools. One week later, the number of reported incidents of harassment and intimidation had reached 701, and incidents in schools had risen to 149. On November 29, SPLC released The Trump Effect: The Impact of the Election on Our Nation’s Schools. The report chronicles survey responses from over 10,000 educators across the country. The shocking results: 90 percent reported that their school environments had been negatively impacted by the election. Forty percent reported hearing derogatory comments directed at students of color, immigrants, Muslims and/or LGBTQ from their fellow classmates.

“There are 54 million students in American schools,” Maureen Costello, the director of SPLC’s Teaching Tolerance and the report’s author, told Truthout. “There are more students in K to 12 schools than there are in colleges.” In schools across the country, people who are different from one another are brought together, increasing the likelihood of volatile incidents.

“There’s Been an Escalation of Events Post-Election”

In the days after the election, reports of students bullying their peers based on race, ethnicity and religion increased dramatically. Some incidents involved children in elementary school. In Royal Oak, Michigan, the day after the election, a group of middle schoolers chanted, “Build the wall!” echoing one of the rallying cries at Trump’s campaign events. Three days after the election, a Minnesota student forcibly removed a Muslim middle schooler’s headscarf before pulling her hair. Four days later, the girl had not returned to the school, where she feels unsafe. The fear is not unfounded. In a different Minnesota elementary school, a fifth-grade student threatened to shoot a Somali third-grader, bringing an air pistol to school. (A school bus driver intervened and took his gun away.) In Atlanta, three white children, including a 13-year-old, attacked an eight-year-old Black boy. The boy was hospitalized for a broken arm and concussion and now has post-concussion syndrome.

The SPLC has heard of incidents involving children as young as five and six years old. “It’s from pre-K all the way to higher education,” said Costello. She notes that younger children often repeat what they’ve heard at home or from other sources; sometimes they act to engender a reaction or because they think their actions are funny. These acts include grabbing girls and saying, “You’d better get used to that” or asking immigrant classmates, “Have you packed your bags yet?”

“It’s hard to tell whether the intent [to intimidate or harass] is there,” said Costello, adding that what matters is not intent, but impact.

Christian, a Black 15-year-old at LaDue Horton Watkins High School in Missouri, definitely felt the impact of emboldened bigotry in the wake of the election. Two days after the election, Christian’s 3D design class was nearly over when a 17-year-old classmate began poking him in the arm with a hot glue gun; he also placed a blob of hot glue on Christian’s chair. Not realizing this, Christian sat on the hot glue. The other student then spread more hot glue on a piece of paper and slapped it on Christian’s arm, burning it.

When Christian came home that afternoon, he still had hot glue stuck to his arm. His mother, Lynette Hamilton, took him to the emergency room, where he was treated for third-degree burns. She then demanded to speak with the school’s principal. Initially, she was told that she needed to make an appointment and that the principal’s earliest available date was five days later. She left her phone number. Four hours later, the principal called to tell her that the school was investigating and would get back to her later.

Hamilton told Truthout that this was the first time her son had ever experienced anything like this. But, she noted, “there’s been an escalation of events post-election.” That same afternoon, on a LaDue school bus, two white students chanted, “Trump, Trump, Trump,” at Black students; one white boy told the Black students that they should sit in the back of the bus.

Tango Walker-Johnson, the mother of one of the students harassed on the bus, described the incident to the school board five days later, saying, “This is the fifth racially charged incident that has occurred with my daughter since the beginning of the school year.” She was one of the 140 parents and students who packed the school library to tell the all-white school board about racist harassment and attacks at the school.

Hamilton also attended the meeting. As she listened to other parents’ stories, she realized the magnitude of racism occurring at the school. “I had no idea,” she said, “and my child has been going there since fourth grade.” That night, she made the decision to make her Facebook account public and post several close-up photos of her son’s serious injuries. “I wanted everybody to see why I kicked up a fuss,” she explained.

The LaDue School District has since issued a public statement. Noting that student privacy laws prohibit disclosing disciplinary information, the statement said that the two students involved in the bus incident had served the entire assigned discipline period. LaDue police have filed third-degree assault charges against the boy who burned Christian. While the statement did not note either boy’s race, the school board said the boy facing charges is Latino.

Meanwhile, Christian is reminded of the incident any time he moves his arm, showers or even lies in certain ways. To avoid the pain, he keeps his arm in certain positions. “It will heal so it’s not sore, but he will have a lifetime mark on his arm,” his mother said.

“They Look at Him and Say, ‘If Trump Can Say It, I Can Say It'”

In Converse, Texas, 18-year-old Jaaezus, a Black senior at Judson High School, refused to allow a white classmate to get away with harassing him. On Election Day, Jaaezus was walking down the street when his classmate drove past. “He shouted ‘You’re a n—,’ and flipped me off,” the 18-year-old told Truthout.

The next morning, Jaaezus walked into his first period class and sat next to that student. “I wanted to know why he felt that way, why he felt it was OK,” he explained. “I said, ‘Excuse me, you drove past me yesterday, you called me a racial remark and you flipped me off. Why would you think that’s OK? We’re in 2016. We don’t do that anymore.'”

According to Jaaezus, the student claimed not to know what he was talking about. Jaaezus pressed the point until the boy muttered under his breath, “You don’t want to be called a n—-, but you want to act like one.” He then changed his seat, but Jaaezus wasn’t finished talking to him. Cell phone videos by other students show him being held back by another student as he said, “I’m tired of hearing your shit, so what’s up?… You was bold enough to say n—-, so what’s up?”

Jaaezus said that racist remarks have been a recurring problem with this particular student. The previous year, the same boy told him that he should be picking cotton. But at the beginning of this school year, Jaaezus said that he approached the boy and told him that he didn’t want any trouble. “We agreed on that,” he remembered. But then the election happened and their agreement seemed to have been forgotten.

“Trump has set an example for people that saying ignorant and snide remarks is OK, when it’s not,” he reflected. “They look at him and say, ‘If Trump can say it, I can say it.'”

“I think a lot of what’s happening is related to the election, what Trump said during the debate and on social media,” agreed Hamilton.

When speaking with Truthout, Enriquez noted several times that she had never had a problem with her classmate, even when discussing politics, until the day after the election. “He was never mean to me,” she said. But Trump’s election seems to have emboldened students to harass, threaten and intimidate their peers of color. “People watching him think it’s OK [to say these things now],” she reflected.

In the lead-up to the election, Enriquez’s seven-year-old sister told her that some of her second-grade classmates had said that, when Trump wins, all the Mexicans will be gone. Given that their mother is from Mexico, the comments frighten her sister. “She asked what will happen when Trump wins,” Enriquez recalled. Each time, Enriquez has had to assure her sister that their mother — and their family — would be OK.

“Many things Trump has said have been weaponized. His rhetoric, like ‘Build the wall,’ is repeated,” stated Costello. She pointed out that even the president-elect’s name has been weaponized, ranging from graffiti to chanting his name repeatedly. “This is the classic way that we define bullying — it’s negative and repeating. I don’t think anyone can argue that it’s not related to the election.” Over 2,500 educators told the SPLC about incidents in which Trump’s name or election rhetoric had been invoked, whether through graffiti, assaults, fights or threats of violence.

Students Voice Their Outrage

Some schools are taking a proactive approach to preventing bullying and harassment. In some schools, faculty and staff arrived at school early to plan the day, sometimes agreeing to jettison the curriculum to allow students the time and space to discuss the election, their feelings and their fears. Some made announcements reminding staff and students to remain respectful of each other.

In New York City, 15-year-old Aysha M. told Truthout that the day after the election, administrators at her school made an announcement reminding its 1,500 students of various ethnicities and religions to respect each other.

That same day, a handful of white students walked down the stairs repeating, “Ever since the election, Muslims have been saying, ‘Allahu Akbar'” and laughing. Several others asked them to stop; they did. That’s the only post-election incident that Aysha knows of; she has not personally been harassed. Aysha credits the lack of bullying to the teachers’ constant reminders to students to be respectful.

New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman and State Commissioner of Education MaryEllen Elia have since sent a letter to school officials throughout the state reminding them that the 2012 Dignity for All Students Act requires schools to provide an environment free from discrimination, harassment and bullying at schools, on school buses and at school functions. The letter asked school districts to ensure that their Codes of Conduct included addressing racism and other forms of bigotry.

In Missouri, the LaDue School District prepared a document outlining several steps being taken in response to recent incidents. These steps include working with Educational Equity Consultants, which offers a Leadership and Racism Program to schools nationwide; meeting with students of color to hear their concerns; and planning staff trainings and student engagement in the coming months.

In other schools, students aren’t waiting for officials to take the lead. In Shaker Heights, Ohio, high school students walked out in protest of both Trump’s election and the suspensions meted out to their classmates who posted another student’s racist comments online. In Missouri, six days after Christian was burned, over 100 LaDue students walked out of classes. They rallied in front of the school, where several spoke about their own experiences with racist acts perpetrated by their classmates, then marched to the nearby administration building.

Across the country, high school students have organized mass walkouts to protest Trump’s election. In Silver Spring, Maryland, a northern suburb of Washington, D.C., over 500 students walked out of class the Monday following the election chanting, “We reject the president-elect,” and blocking traffic on a busy downtown street as they marched. That same day, hundreds of students in Portland, Oregon, also walked out and marched to City Hall. The following day, despite warnings of disciplinary sanctions by the city’s Department of Education, nearly 1,000 New York City students walked out of class and into the cold rain, converging upon Trump Plaza in midtown Manhattan.

For parents concerned about increased intimidation at their children’s schools, Costello emphasizes focusing on safety, courage and respectful dialogue. “Our first job is to make kids feel safe,” she said. That means not just talking to children, but actively listening to them. Ask what they’re feeling, what’s happening at school, and what concerns they have, she said. They should also encourage respectful dialogue at all times.

Finally, Costello noted that we must get past the fear that leads many to look away when others are being bullied.

“We have to encourage ourselves and our children to intervene when they see something ugly,” she said. This may not mean rushing into a situation like Superman landing in the midst of a battle; instead, it may mean signifying disapproval when hearing racist remarks and making sure the kids being targeted are not alone. “Don’t just say, ‘I’m here for you,'” Costello said. “Show them that. Go and sit with them. Go and be with them.”

Media that fights fascism

Truthout is funded almost entirely by readers — that’s why we can speak truth to power and cut against the mainstream narrative. But independent journalists at Truthout face mounting political repression under Trump.

We rely on your support to survive McCarthyist censorship. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation.