Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

If Indi Tisoy has a single dream, it is to reach the United States. Her desire is so strong, in fact, that she waits at the border because it makes her feel closer to that dream. Tisoy, who is a member of the Inga Indigenous community, left the Colombian Amazon’s Putumayo department with her family when she was 12 to seek better economic opportunities in the city of Bucaramanga.

When Tisoy was 20, she began transitioning. Within five years of her transition, Bucaramanga, which was once her refuge, no longer felt safe. So in late 2024, Tisoy, who is now 25, decided to begin journeying toward the United States because she’s drawn to what she calls the country’s “open-minded culture.”

“The last time I went [to my community] was very difficult because there was criticism, insults, threats, and I made the decision to leave Colombia,” Tisoy said from a migrant shelter in northern Mexico. “I said I’m [also] not doing well in Bucaramanga, so I want to change my life.”

Since taking office, U.S. President Donald Trump has taken a series of executive actions targeting migrants as well as transgender and nonbinary people. For trans migrants like Tisoy, who are already undertaking arduous journeys to the United States, asylum options have been shut down, and the hope of finding safe haven is dwindling.

In response to the changing environment, key initiatives in Mexico are focusing on developing more long-term and comprehensive support for LGBTQ migrants, who may be in Mexico for a longer time than originally intended.

A Continuous Search for Safety

The LGBTQ community experiences continuous displacement, especially if they are rejected by their communities and families and are seeking access to medical care. However, there is little data on LGBTQ refugees and asylum seekers in the U.S., which hinders a better understanding of their characteristics and experiences.

A study by the Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law found that between 2012 and 2017 an estimated 11,400 asylum applications were filed by LGBTQ individuals. Nearly 4,000 of these applicants sought asylum specifically due to fear of persecution based on their sexual orientation or gender identity.

Raúl Caporal, director of Casa Frida, which provides refuge for LGBTQ migrants in Mexico City, Tapachula, and Monterrey, Mexico, explained that the majority of the individuals they serve are fleeing violence and seeking international protection.

“The population we focus on leaves their countries because of persecution and violence motivated by sexual orientation, gender identity, and expression,” Caporal says.

“[This is compounded] by organized crime taking advantage of their vulnerability, the absence of the state, and the inability to access justice institutions when they try to report crimes.”

Latin America and the Caribbean report the highest number of trans murders of any region in the world. According to Transrespect Versus Transphobia Worldwide, 70% of trans murders globally occur there, with the majority of victims being Black trans women, trans women of color, and trans sex workers. In Mexico alone, according to data from Mexico’s National Trans and Nonbinary Assembly (Asamblea Nacional Trans No Binarie), more than 55 trans people were killed last year, making it the second deadliest country in the world for trans people, after Brazil.

Brigitte Baltazar, a Mexican trans activist who resides in Tijuana, Mexico, after being deported from the U.S. in 2021, explains that trans asylum seekers no longer see the U.S. as a safe haven as Donald Trump signs harsh executive orders targeting trans and nonbinary people as well as immigrants. Baltazar says that these executive orders “increase the stigma and discrimination [trans migrants are] already experiencing,” which “creates a state of panic.”

Though Casa Frida documented that 67% of the people they served in 2024 didn’t have the U.S. as their final destination, the remaining 33% intended to reach the U.S. using CBP One, a mobile app that migrants can use to apply to enter the U.S. However, that option was discontinued by the Trump administration in January.

Activists and organizations agree that strengthening access to asylum in Mexico, along with health care and job opportunities, is key to sustaining support for trans migrants.

“Mexico has a great opportunity to strengthen its local public policies on integration, particularly at the municipal and state levels,” Caporal adds. “Ultimately, it is the municipalities where refugees will reside, where they will find work close to their homes, where they will generate an income, and where people can continue their studies.”

Strengthening Support Systems for Trans Migrants in Mexico

The persecution and violence LGBTQ individuals face often continue during their journey. Shortly after crossing the Mexico-Guatemala border, Tisoy and a fellow group of migrants were kidnapped. She recalled being held in the backyard of a house for 12 days until her best friend in the United States could raise $1,000 to meet a ransom demand.

Caporal explained that the lack of state protection and inaccessible justice institutions increases the vulnerability of trans migrants, making them easy targets for organized crime. In its latest report, Amnesty International highlights the risks and precariousness faced by people in the U.S.-Mexico border, at the hands of both state and non-state actors. The report warns that many migrants are forced to pay bribes to Mexican authorities, criminal groups, or individuals at checkpoints.

Tisoy arrived in Matamoros, Tamaulipas — a city less than three miles away from Brownsville, Texas — days before Trump’s inauguration. She planned to cross the river and request asylum, but she didn’t have the $200 fee she needed to pay the cartel to cross. With deportations beginning, she now waits near the border as she doesn’t want to risk being taken back to Colombia.

“In this journey, you have to be very positive because if you get depressed, you’re in a city that isn’t yours, in a country that isn’t your own,” Tisoy says. “I cried and prayed a lot, but then I realized I had to keep going. I wiped away my tears and here I am.”

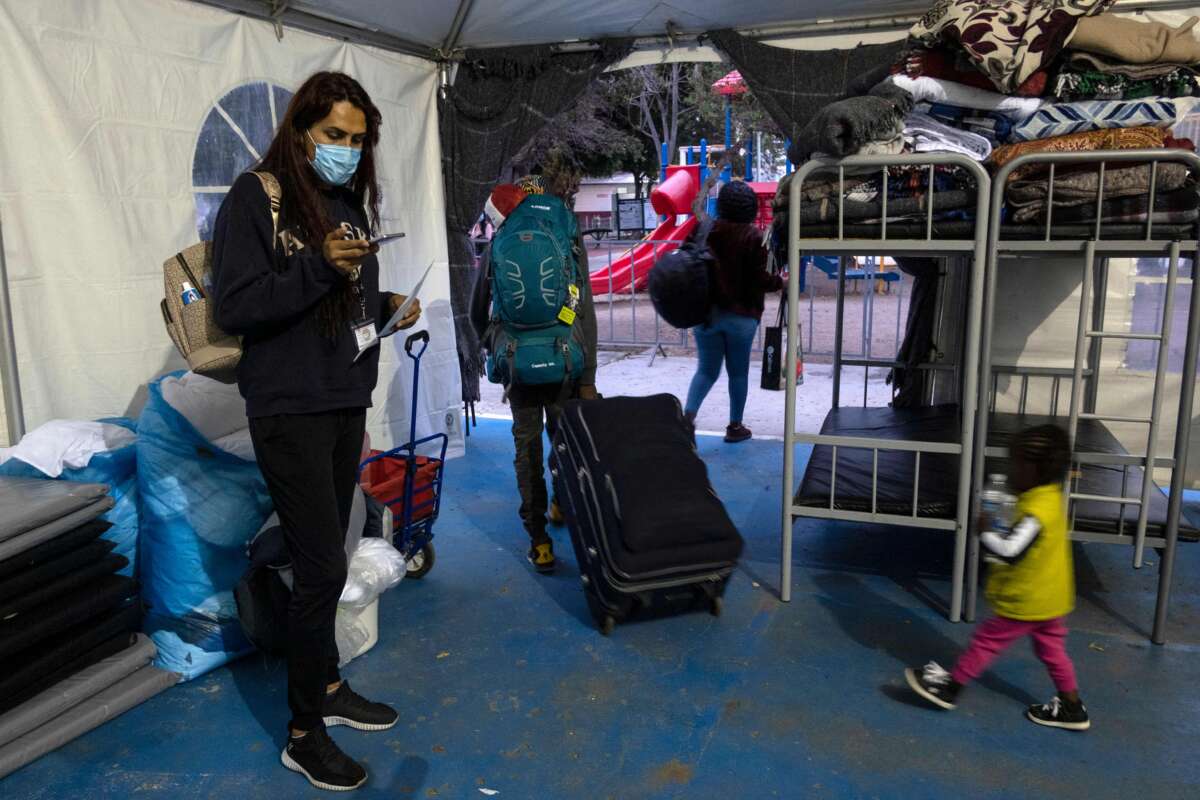

Waiting near the U.S.-Mexico border is increasingly dangerous. Most migrants in Matamoros remain in shelters due to threats of being kidnapped and robbed. For Tisoy, even being at the shelter can be uncomfortable due to the lack of specific support for LGBTQ individuals.

After families complained about her presence in a shelter with children, she moved to a neutral room in a nearby shelter, but her stay is uncertain with more migrants seeking an extended stay in Mexico. “I arrived normally, and no one had said anything to me,” Tisoy explained. “Then one mother said I was trans and went to complain, but I didn’t understand why she did it.”

After the cancellation of CBP appointments, some migrants returned to Casa Frida to seek legal advice for requesting asylum in Mexico. To seek asylum in Mexico, individuals must apply within 30 days of arrival at a Commission for Refugee Aid (COMAR) office. The application requires completing a form explaining their reasons for leaving their home country, providing supporting documentation, and detailing their fear of persecution based on factors such as race, religion, nationality, political opinion, gender, or social group membership.

Casa Frida, along with other organizations, is currently working with COMAR to find alternatives to the 30-day rule for those who didn’t apply for asylum because they were waiting for their CBP appointment. Caporal says that Mexico must strengthen its asylum system and provide COMAR with the resources to meet the increasing demand for guidance, incorporating both gender and sexual diversity perspectives.

“We are preparing a draft bill to reform the refugee law in the Chamber of Deputies, which seeks to include persecution based on sexual orientation and gender identity as a direct cause for obtaining and recognizing refugee status,” he added.

Guaranteeing Safe and Dignified Spaces

Along with legal counseling, Baltazar said “dignified access to health care” is also a critical need. Baltazar, who also coordinates the LGBTQ program at the migrant organization Al Otro Lado, explained that Mexico’s bureaucratic and often inhumane health system poses a significant challenge, particularly for trans individuals.

She regularly accompanies trans migrants to health centers to access antiretrovirals or STI medications, a challenge even for internally displaced Mexicans. The lack of documentation — common for both domestic and foreign migrants who fled without documents or lost them on their journey — further complicates their access to proper health care.

“With hormone treatments, unfortunately there is no program and there are no specialized doctors, like endocrinologists, who can care for this population,” Baltazar added. “This puts their health at risk since they do not have a hormone treatment controlled by a specialist.”

Tisoy has been struggling to get tested after being sexually assaulted on the train north. “I spent 15 days on the train, and I was raped. So it’s important to me to get tested,” she says. During a stop at Casa Frida in Mexico City, she tried to get tested, but after three days, she decided to continue her journey rather than waiting.

Before Trump’s inauguration, there was a focus on helping people “while they were able to cross,” but now, Baltazar says there’s an urgent need for a longer-term strategy where people can access health care and other services and opportunities in Mexico.

“People cannot return to their countries or regions because their lives are in danger. The idea is to offer them workshops and integration support, giving vulnerable people tools so they can do anything in a new country,” Baltazar added. “Perhaps they even discover passions they didn’t have the opportunity to explore in their countries because they weren’t free or didn’t have access to schools, universities, or job training.”

Most shelters and resources for LGBTQ asylum seekers rely on grassroots efforts by activists like Baltazar and organizations like Casa Frida, which depend on volunteer and community support. Casa Frida obtained external funding to continue growing, but nearly 60% of its 2025-2026 budget is at risk due to USAID cuts.

Though they are developing an emergency plan to continue operations, Caporal warned that wait times for services will likely increase. “Our operational capacity will likely be reduced,” Caporal says. “This may result in longer wait times for those who visit our facilities daily and we will have to ensure that we continue providing the 54,000 meals we serve daily.”

Caporal agrees that the focus should be on strengthening paths to settle in Mexico and pushing to implement these integration policies, particularly at the local level. Casa Frida is concentrating on these local integration opportunities, providing a safer environment where individuals can explore a wide range of life options.

“That is when they begin to make the decision that in reality it is not that they want to reach the United States,” Caporal added. “In reality what they want is to reach a safe territory where they can live in freedom, autonomy, and — above all — with pride in being who they are.”

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout’s fundraiser ended last night, and we fell just short of our goal. But your support still matters immensely. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your help.