Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

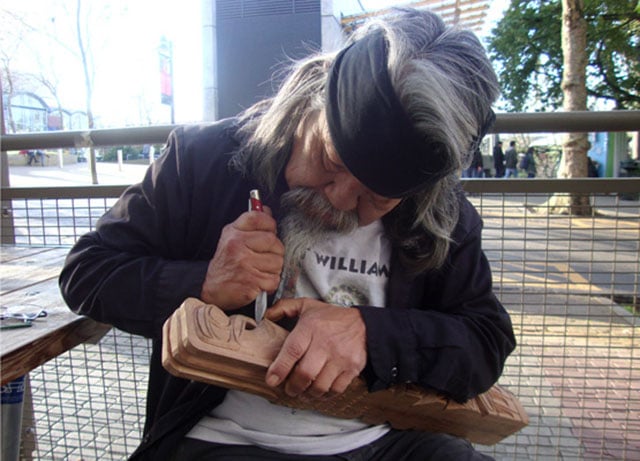

Rick Williams carving in Seattle City Center. Photo by Kayla Schultz.

Rick Williams carving in Seattle City Center. Photo by Kayla Schultz.

Rick Williams sits outside Seattle’s Space Needle carving totem poles until dark, a workday that can reach up to 12 hours. Tourists and Seattleites approach the picnic table where he sits, examining the intricate designs he carves with only a pocket knife. The children in his family were taught to carve when they were about 7 years old, with techniques passed down through generations. The Williams family legacy in Seattle started in the 1920s, when grandfather Sam Williams began carving for Ye Olde Curiosity Shop. Although he has lost many of his family members through the years, Williams holds their traditions and memories close.

In August 2010, Williams was reunited with his brother John T. Williams. For two days they sat at a bench in the city, carving with other family members and catching up on the years they spent apart. John had lost hearing in his left ear, and his sight was deteriorating. He went for a walk, saying he would return shortly, but on his way back a police officer spotted the knife in his hand. Born into a family of First Nation master carvers, John usually carried the knife around, along with a piece of wood. The officer yelled for John to drop the knife, and seconds later fired his gun four times, killing him.

With the recent deaths of Eric Garner and Mike Brown, who were also killed by police officers, Rick Williams noted the connections between those police-related incidents and the one involving his brother. In each case, the officers used excessive force when the situations could have been de-escalated by other means, according to Williams, who called the incidents a “sickness.” Although problems may be rooted in basic police training, they are also influenced by perceptions of danger based on race and culture.

When the grand jury ruled not to indict Darren Wilson, the Ferguson, Missouri, officer responsible for the death of Mike Brown, the victim’s family asked protesters to keep the gatherings peaceful—something Williams had also asked in honor of his brother four years ago.

Rick Williams holding a totem pole he hand-carved and painted. Photo by Kayla Schultz.

Rick Williams holding a totem pole he hand-carved and painted. Photo by Kayla Schultz.

“The family from Ferguson asked for peace and calm, and I literally fell out of the couch I was sitting on because he said the same thing I did: peace and calm,” Williams said. “And I’m like, thank you, they are listening. The only way you can help change the system is show them you are a human being and [say], ‘You have [taken] something from me you shouldn’t have. How dare you?’”

After John’s death, people in Seattle began filling the streets in protest. Native American communities came together, playing traditional drums to honor John. Other protesters held signs that read “Another stolen life. Stop police brutality.”

As the protests started to escalate, Williams wondered how his family could coexist with a police department that didn’t understand his culture and quickly reacted with gunfire.

Andrea Brenneke, Williams’ lawyer, suggested arranging a restorative circle that would bring the family and police together to candidly discuss: the effects of the shooting; how to bridge the cultural gap between Native Americans and police; and ways to prevent unwarranted killings in the future. Both Police Chief John Diaz and Williams agreed to the restorative circle. Having no previous experience in conducting them, Brenneke started researching restorative circles and how to get the best results. About two weeks after the shooting, they met.

Williams and his brother Eric had the chance to speak directly to six representatives of the police department at the restorative circle, which also included two family friends, two facilitators (one being Brenneke), and two people from the Chief Seattle Club, an organization that gives aid to American Indians and Alaska natives.

“It took a lot of leadership for [the police department] to have a conversation,” Brenneke said. “We wanted to create a safe space to engage and address issues, and meet those needs.”

Everyone had agreed that the details of the shooting were off-limits for discussion—it was still under investigation. Instead, they would focus on how the city’s Native American communities felt disrespected and misunderstood by the police, and how interactions had become strained.

The shooting had created fear among Natives, especially those who were carvers. Williams relied on the money he made selling totem poles on the streets of Seattle, and was worried about his safety and the safety of other street artists. He often dug into pieces of wood as he walked around the city, but now didn’t feel comfortable, even where he first learned the art. Native art and history are deeply embedded in Seattle culture, so many didn’t understand how an officer could be ignorant about the items John was holding when he was shot.

Rick Williams carving his name into a totem pole a customer purchased. Photo by Kayla Schultz.

Rick Williams carving his name into a totem pole a customer purchased. Photo by Kayla Schultz.

In Brenneke’s article accounting her experience in the restorative circle, she said there had been complaints of police making comments to the Williams family, causing more tension.

“A teenaged member of the Williams family asked an officer, ‘I am a carver, and these are my tools. If I have this knife, will you shoot me too?’ The officer responded, ‘You don’t want to test that theory now, do you?’” Brenneke wrote.

During the restorative circle, the group spent three hours talking about those issues, and created an action plan, which the Seattle Times published. Police training was the main topic of discussion, including the agreement for the department to explore anti-racism training, create a mentoring system between senior and junior officers, and teach the department Native American customs, like carving, that they should be aware of while on duty. In the months after the restorative circle, Williams and the police had follow-up meetings where they shared progress made in the action plan.

“I see a lot of changes [in the Seattle Police Department]; slow, but I see a lot of changes,” Williams said. “This [restorative] circle can take off. It can work.”

After finishing the restorative circle, Brenneke and the Seattle Police Department began working on a pilot program called the City of Seattle Restorative Justice Initiative. Brenneke became the director for a year, but the city council eliminated the pilot program’s funding in 2014.

The elimination of the program didn’t stop communication, however. After the Darren Wilson ruling was announced, and Seattle’s streets were again filled with protesters, police were invited to converse with people at a community center.

Brenneke said that people were not happy—they were angry and wanted the police to leave. But she and the other organizers wanted the police in attendance because it allowed open dialogue where many perspectives could be discussed and understood. She said the police officers shared their personal feelings and how they were affected by the ruling.

“Protests are very important, but in addition, it’s important for people to have a deeper dialogue,” Brenneke said. “Dialogue encapsulates a different thing, a profound thing where you learn at an intimate level how it’s affecting someone else.”

The police department was unavailable for comment, but former Seattle Police Chief Norm Stamper said he’s been an advocate of restorative justice for decades.

“Restorative justice makes infinite good sense, especially when police officers come with an open mind and heart,” he said. “Police are resistant to criticism and say, ‘You don’t know what it’s like for us. We want to go home at the end of each shift.’”

Stamper said that police need to assess the ways they approach perceived threats so they can create safer outcomes. In the aftermath of Ferguson, Missouri, and New York, task forces will probably spend months or years studying police practices to create proper training, but restorative circles could help promote healing in the meantime, said Stamper.

A 34-Foot Totem Pole Keeps Williams Going

Totem pole carved by Rick Williams. Photo by Kayla Schultz.

Totem pole carved by Rick Williams. Photo by Kayla Schultz.

Williams didn’t realize his story had been heard around the world until a woman from Finland messaged him through Facebook looking for guidance. Her loved one had been killed by a police officer. Williams told her to stay calm despite the anger and to not react destructively. With his words of encouragement, she ended up winning her case, and was so grateful for his help that she made a special trip to Seattle.

“She came here and gave me a hug and thanked me, and I was like, ‘Who are you?’” he said laughing.

Williams said that carving is what saved him and keeps him going. He had been so angry after the death of his brother that he punched a tree, leaving an indentation in it. He knew he had to harness the anger, and, in March 2011, he started the John T. Williams Memorial Totem Pole Project, where he began carving a 34-foot totem pole for his brother.

As Williams peeled the bark off, he started to envision what it would look like. His family and friends started carving, and as people visited the site, Williams shared the story of his brother, inviting onlookers to help carve or sand the wood.

In February 2012, the finished totem pole was ready to be erected next to the Space Needle in the Seattle Center. Close to 100 people helped carry the pole from the waterfront, a distance reaching a mile and a half.

Totem pole located in Seattle City Center carved in memory of John T. Williams. Photo by Kayla Schultz.

Totem pole located in Seattle City Center carved in memory of John T. Williams. Photo by Kayla Schultz.

“I put my heart and soul into that totem project,” Williams said. “Everybody that [my family] touched in our lives was there carrying the totem.”

Williams said that his grandfather, father, and sons had never seen him with tears in his eyes, but he felt overwhelmed with energy when the totem pole was being raised. With the help of carving and community encouragement, he found a way to heal and help others.

“I keep telling the cops that for the rest of my life I will see my brother fall,” Williams said, “But I will always stand up for the people out there.”

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to add 500 new monthly donors in the next 10 days. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.