Truthout is a vital news source and a living history of political struggle. If you think our work is valuable, support us with a donation of any size.

Every day, as they burn with nuclear fission at some 571 degrees Fahrenheit, some 430 nuke reactors roast our Earth. They irradiate and superheat our air, rivers, lakes and oceans.

They also spew radioactive carbon, and emit more greenhouse gasses in the mining, milling, enrichment and fabrication processes that produce their fuel. Still more is emitted as they attempt to store their wastes.

Six big reactors and their fuel pools now threaten an apocalypse in Ukraine. Pleas for United Nations intervention are increasingly desperate.

But “nuclear renaissance” proponents say we need even more reactors to “combat climate change.”

However, these mythical new reactors have real costs — and for at least the next six years, they can produce nothing of positive commercial or ecological significance.

The primary reason there’s likely to be no new reactors in the U.S. until at least 2030 (if ever) is economic — the cost of construction is gargantuan.

Let’s consider eight recent major construction failures in Europe and the U.S.

Atomic plants were first constructed during the Manhattan Project that built the atomic bomb. Heralded as the “too cheap to meter” harbinger of an atomic age, the first commercial reactor came online at Shippingport, Pennsylvania, in 1958.

But in the coming decades, as reactor construction took off through the 1960s, ‘70s and into the ‘80s, the industry demonstrated an epic reverse learning curve, what Forbes called in 1985 “the largest managerial disaster in business history, a disaster on a monumental scale.”

At VC Summer Nuclear Station in South Carolina, after a decade of site work marred by faulty construction, substandard materials, bad planning, labor strife, and more, two reactors were abandoned outright in 2017, wasting $10 billion while bankrupting Westinghouse.

By comparison, the previous largest nuke-related bankruptcy, at the Washington Public Power Supply System in 1982, cost about four times less, at $2.5 billion. The biggest solar failure, at Solyndra in 2011, came with the loss of a $535 million government loan, about 15 times less than VC Summer.

In Georgia, two still-unfinished Vogtle reactors are some seven years late and $20 billion over budget, now at a staggering $35 billion plus.

In Hinkley, United Kingdom, two more reactors are also years late and could surpass $42 billion.

In Flamanville, France, a single reactor project begun in 2007 is still unfinished, years past its original promised completion date, and four times over its original cost estimate — with the price tag now beyond $14 billion.

Finland’s Olkiluoto has opened after 18 years of construction at around $12 billion in costs so far — three times the original promise.

All these reactor projects failed due to overly optimistic industry promises designed to attract investors, followed by poor execution, bad design, substandard components, labor strife, and more. Despite the industry hype, none of these eight reactors can ever compete with renewables, whose prices now range as low as a third to a quarter of nuclear — and are dropping.

With incalculable billions and a decade or more needed to build old-style big nuclear reactors, financial experts have long predicted that the necessary capital won’t be anywhere on the horizon.

Instead, the industry has been gouging state and local governments to keep the old reactors running, a desperate and dangerous toss of the dice.

Six billion dollars was pledged to nuclear energy plants in Biden’s infrastructure bill alone. A billion in federal dollars has been promised to keep California’s Diablo Canyon running, along with another billion from the state.

But the average age of an operating U.S. reactor is now around 40. None are insured, despite assurances dating to the 1957 Price-Anderson Act that the reactor fleet would get private liability coverage by 1972. Despite their immense inherent danger, only nominal company participation in a perfunctory insurance fund has been required for a license. Blanket coverage against a cataclysmic accident has not been a legal requirement to build or operate these reactors.

After six decades, reactor owners are still exempted from the costs of a catastrophic accident, and no nongovernmental insurance corporation has stepped in at an appropriate scale.

Yet the dangers escalate as the plants age. Meaningful estimates of the cost of a catastrophic accident are hard to come by, but after Chernobyl and Fukushima, the costs have soared into the trillions.

The oldest operating U.S. plant, at Nine Mile Point on Lake Ontario, opened in 1969. Repeated near-disasters at Davis-Besse in Ohio include a hole eaten through a critical core component by boric acid that was missed because the owners refused to do required inspections. Monticello and Prairie Island in Minnesota threaten the entire Mississippi Valley. Critical intake pipes at South Texas recently froze, as its builders never anticipated the cold weather that hit it unexpectedly in 2021.

French and U.S. rivers are often too hot to cool reactor cores, forcing them to cut output or shut altogether.

Palo Verde in Arizona evaporates some 27,000 gallons of water per minute in a roasting desert. San Onofre in California was shut in 2012 because of leaking generators and now stores its high-level waste 100 feet from the ocean. Perry (Ohio) and North Anna (Virginia) have both been damaged by earthquakes.

Former Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) site inspector Michael Peck has warned that Diablo Canyon in California should be closed because of the danger posed by seismic activity. Just 45 miles from the San Andreas Fault, Diablo was on its way to an orderly shut-down when Gov. Gavin Newsom strong-armed the state legislature and Public Utilities Commission to keep the embrittled, under-maintained reactors open despite their ability to blanket the state in terminal radioactivity. The NRC ignored Peck’s warning and he’s now gone from the Commission.

Diablo’s owner, Pacific Gas & Electric, has a blemished record when it comes to public safety — it has admitted to more than 80 counts of felony manslaughter due to the 2018 wildfires in California.

In Ukraine, of six reactors at Zaporizhzhia, five are in cold shut-down while one lingers on to power the place. But six shaky fuel pools contain apocalyptic quantities of radiation. Power supplies are in doubt, vital cooling water is threatened by a sabotaged dam, military attacks are possible, and site workers maintain the plant in a state of terror.

Like Zaporizhzhya, any operating reactor or fuel pool would be devastating targets for military or non-state terrorist attacks. The 9/11 masterminds reportedly toyed with hitting the Indian Point power plant north of New York City, irradiating the northeast. Any of the 90-plus decayed uninsured U.S. nukes are potential Chernobyls or Fukushimas. Deep concerns have been expressed by United Nations inspectors and many others. A public petition now asks that UN peacekeepers take over the Zaporizhzhya site.

So, taken in sum, “nuclear power” to date is defined by catastrophic fiscal failure and public risk. No new plants are under construction and efforts to keep the current fleet operating are fraught with uninsured danger.

In straight-up financial terms, the peaceful atom’s “too cheap to meter” promises can never compete in real terms with renewables, which won’t melt, explode, release mass quantities of radiation or create atomic wastes.

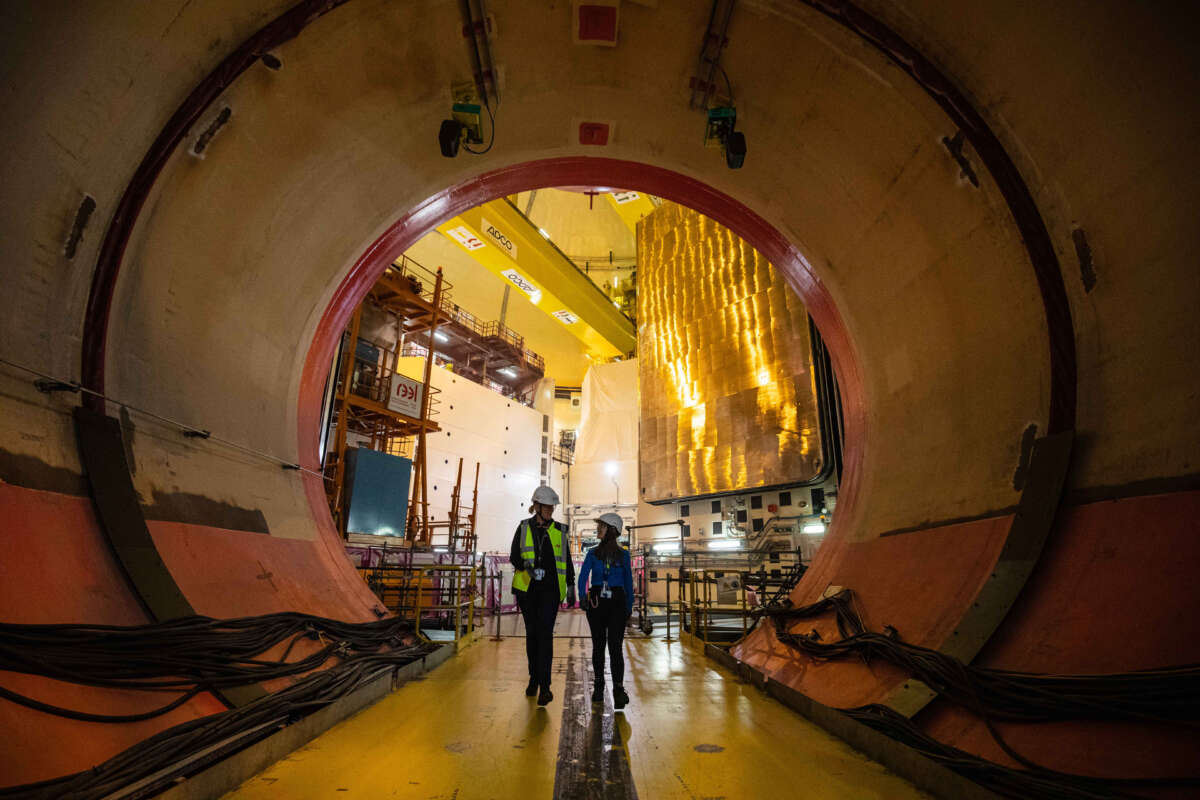

Projections for thorium, fusion, and other futuristic reactors also remain technically and fiscally vaporous. The fusion facility at ITTR in France has already burned through $65 billion.

And a reactor burning at 100 million degrees is as likely to cool the planet as Edward Teller’s fusion superbombs.

Which leaves us with the much-hyped small modular reactors (SMRs), now wallowing in deep delay and soaring prices. SMRs are theoretical nukes designed to be far smaller than today’s 1,000+ megawatt reactors, to be mass produced and buried throughout the country. Only one SMR developer, NuScale, has gotten significant preliminary licensing approval. Cost and delivery projections from Bill Gates’s TerraPower, X-Energy, and other prospective manufacturers are theoretical, with little concrete data to back up when they might be deployed and at what prices.

Projected prices at NuScale have soared from $58/megawatt-hour in 2017 to $89 now, nearly double the range of wind and solar. By 2030, SMR prices are likely to be triple or more. A recent piece by former NRC Chair Allison MacFarlane eviscerated the technology’s potential with a devastating analysis, referring to it primarily as a means of attracting government hand-outs and “stupid money.”

But with no big U.S. reactors being built while SMRs drown in red ink and tape, the industry still burns and irradiates the planet with about 430 aging reactors worldwide and 92 ancient ones here in the U.S. And the odds of an apocalypse at one or more of those old reactors grow with each day they age.

The pitfalls include unsolved problems of reactor waste, deteriorating infrastructure, a fast-retiring workforce, a diminishing ability of the industry to deliver on its promises, a minimum five-year gap before any small reactors could come into significant commercial production, the forever threats of war and terrorism, the killing power of radiation, and much more.

Meanwhile, renewables have long since blown past both nukes and coal in jobs, price, safety, efficiency, reliability, speed to build, and more.

As nuclear investments dry up, offshore wind, rooftop solar, “agri-voltaic” farmland and advanced efficiency are booming.

A pending transition from lithium to sodium may soon transform the battery industry. For reasons of cost, ecological impacts and resistance to mines on Indigenous lands, lithium-based batteries face serious challenges.

But with cheaper, more widely available sodium at their core, battery technologies are poised for a near-term Great Leap. Should that happen soon, the current storage challenges of the green power revolution could all but disappear.

Thus, we face the ultimate test: Can our species replace these failed, lethal nukes with safe and just forms of green power — or will we let this latest atomic con fry us all?

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout’s fundraiser ended last night, and we fell just short of our goal. But your support still matters immensely. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your help.