Given that the author of Guantánamo Diary – Mohamedou Ould Slahi – is still imprisoned there and prohibited from talking with the media, Truthout interviewed human rights activist and writer Larry Siems, who is the editor of Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s handwritten diary. Siems is the former Director of Freedom to Write and International Programs at PEN American Center. He is also the author of The Torture Report: What the Documents Say About America’s Post-9/11 Torture Program.

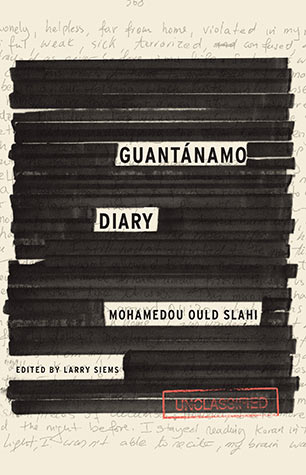

(Image: Little, Brown and Company)Mark Karlin: Can you begin by telling our readers about the extraordinary story of how Guantánamo Diary was written and came to be released?

(Image: Little, Brown and Company)Mark Karlin: Can you begin by telling our readers about the extraordinary story of how Guantánamo Diary was written and came to be released?

Larry Siems: Mohamedou Ould Slahi started writing the pages that would become Guantánamo Diary in the Spring of 2005, right about the time he learned he would finally be allowed to meet Nancy Hollander and Sylvia Royce, two pro bono attorneys who had volunteered to take on his case. When they arrived in GTMO, he handed them about 150 pages; with their encouragement, he continued to write through the summer and into the fall, completing the 422-page handwritten manuscript on September 28, 2005.

Everything Guantánamo prisoners say or write is considered classified from the moment it is uttered or created, and so as Mohamedou gave installments of his story to his attorneys, they would have to surrender them to the US government, which locked them in a secure facility outside of Washington DC. That’s where the manuscript remained for more than six and a half years. For much of that time his lawyers were litigating and negotiating behind the scenes to get it declassifed, and finally, after two rounds of censorship, his attorneys were able to hand me a copy of the manuscript as it was cleared for public release – with its more than 2,600 black box redactions – in the summer of 2012.

How, given his torturous and numbing imprisonment, did Mohamedou Ould Slahi gain the resources and courage to write the diary.

I really can’t imagine how he managed this. It is such a remarkable achievement of emotional stamina, of courage, as you say, and of faith, too – religious faith, for sure – and also a deep faith in the power of the truth and the power of the written word to penetrate one of the world’s most severe censorship regimes.

Mohamedou wrote the manuscript for Guantánamo Diary in the same isolation hut he had been dragged into two years before and tortured to the limits of his physical and psychological endurance – a torture that ended less than a year before he started writing. How in that year he was able not only to reconstruct his epic ordeal so accurately – the government’s own declassified documents make clear that Mohamedou’s account is, among other things, a towering feat of memory – but also somehow to gain the perspective and the wisdom that permeates the book really is beyond me. It says a lot about who he is, and about his gifts and qualities as a person. History’s most extreme moments have a way of finding extraordinary voices, and Mohamedou’s really is such a voice – humorous, ironic, empathic, profoundly curious and infused with experience as recorded by all five of his senses. These are the tools and talents of a good writer, and for Mohamedou, I have to think that they enabled him to reach beyond his immediate situation and suffering and into the lives of others.

What is Slahi’s background? How did he come to be caught up in the US’s detention and torture machine?

Mohamedou is Mauritanian. His background is extremely humble: he is the ninth of 12 children; his father, a nomadic camel herder, died when he was an early teen. His father taught him to read the Koran, which he memorized as a child, and he was an excellent student and a huge fan of German soccer in high school – so much so that he applied for, and won, a scholarship to attend university and study engineering in Germany. He was the first in his family to board an airplane, the first to attend college, the first to earn a university degree.

As a university student in the early 1990s, he twice interrupted his studies and traveled to Afghanistan to join what was then a US-supported effort to topple the communist-led government in Kabul; the first time he trained in an al-Qaeda camp, and the second time he served for a few weeks in a mujahideen unit just before the communist government fell. But when the situation descended into fighting among the various mujahideen factions, Mohamedou had had enough.

He returned to Germany, finished his degree, and worked as an electrical engineer in Duisburg throughout the 1990s. Unable to secure permanent residency in Germany, he applied for landed immigrant status in Canada and moved to Montreal at the very end of the 1990s; he lived there for a few months before deciding to return home to Mauritania for good in February 2000. Chronologically, Guantánamo Diary begins with this trip home, which is interrupted by his first detention and interrogation by US intelligence agents. The book is really a chronicle of his ensuing, US-orchestrated odyssey through a global network of national security prisons, ending, finally, in Guantánamo, where he landed on August 5, 2002, and where he remains to this day.

Slahi was ordered released from Guantánamo by a federal judge in 2010, but he is still imprisoned there. Why? Has he ever been charged?

He has never been charged with any crime, and all of the most sensational allegations against him have repeatedly been discredited. He was first questioned in connection with the so-called Millennium plot because in Montreal he attended the same mosque as Ahmed Ressam, who was apprehended in December 1999 for planning to bomb LAX, but Mohamedou simply was never involved in that plot.

He was for a time similarly alleged to have recruited three of the 9/11 hijackers in Germany, but by the time his habeas case was heard in late 2009, the US government conceded he probably didn’t even know about the 9/11 plot. So his habeas corpus petition came down, basically, to a question of whether his involvement with al-Qaeda in the very early 1990s meant he could be held as an “enemy combatant” some 20 years later.

He won that habeas petition, as you say, with the judge finding, quite correctly, that the al-Qaeda of that era was very different from the organization that later attacked the United States and that Mohamedou was not involved in the later version of al-Qaeda. But the Obama administration appealed that and several other habeas release orders issued around the same time, and those cases have been sent back to federal court for rehearing. Five years later, those cases are still pending.

What does Slahi reveal about Guantánamo in the portions of his diary that are not redacted? Is it possible that as far as the US government is concerned, he is a man who knows too much about US abuses and that the US would be admitting he was illegally detained if they released him?

If Mohamedou’s manuscript had reached the public shortly after it was written, it would have been full of shocking revelations about Guantánamo and about GTMO’s Rumsfeld-sanctioned “Special Projects” torture program. But by the time I got the manuscript in 2012, much of Mohamedou’s ordeal had already been revealed in declassified documents that the ACLU acquired through Freedom of Information Act litigation. The sleep deprivation, the frigid rooms, the masked interrogator known as Mr. X, the female interrogator who sexually assaults Slahi; the ruse in which his interrogation chief poses as a White House emissary and tells Slahi the US has captured his mother and is bringing her to GTMO; a staged “rendition” in which Slahi is driven in a speedboat out into the Caribbean and then dumped into a blacked out isolation cell and abused to the point that he is hearing voices – Pentagon records and Senate and Justice Department and military investigations recounted these same stories well before Slahi’s manuscript was declassified and cleared for public release.

This is almost certainly why the manuscript was finally released: By 2012, the government could no longer claim that the story Mohamedou tells – a story that, as I say, tracks with remarkable accuracy the government’s own documentary record – was an official secret.

It’s an interesting question, the extent to which Mohamedou’s ongoing detention may reflect a continuing desire to suppress his voice and avoid acknowledgements about the many mistakes and outright crimes connected to his case. It is a question that has haunted me for three years and should haunt anyone who reads Guantánamo Diary.

I will say this: I think the most notable achievement of Guantánamo Diary is not that it has exposed previous unknown horrors of the US’s post-9/11 torture program, but that, for the first time, readers can understand what it felt like to be subjected to that program and what that meant on a human level for both the prisoners and the US servicemen and women and intelligence agents who were part of that program. Mohamedou is such an effective communicator of this experience, as Guantánamo Diary shows. He surely has more to say on the subject, and his ability to do so is significantly impaired by his continuing imprisonment.

Despite his harrowing ordeal, Slahi’s humanity shines through. He has managed to maintain his soul. How has he survived with his humanity unbroken?

Again, this just must be who he is – someone with a strength of character that reflects both a deep faith and a kind of unquenchable curiosity about himself, his environment and the human beings who are holding and tormenting him. He simply refuses to do what his captors are doing to him, which is to classify him according to prejudices or stereotypes, or to easy divisions of good and evil and us and them. “I’m not going to judge anybody; I’m leaving that part to Allah,” he writes at one point. “I understand that nobody is perfect, and everybody does both good and bad things. The only question is, How much of each?”

It’s clear that this is not just a writing strategy but a fundamental ethic for Mohamedou, and it is the reason he develops such complex relationships with his guards and interrogators. And it is in the portraits of these men and women that I think Guantánamo Diary earns a place on the shelf of great captivity narratives: It shows us not only the harms our misguided detention and interrogation program have inflicted on others, but on our own soldiers and intelligence officers as well.

In what ways does Slahi’s real ordeal compare to the fictional Kafka book, The Trial?

Most obviously in the sense that Mohamedou can never learn why he is being held and cannot access a process to clear himself of the ever-shifting insinuations and suspicions and never fully-defined allegations. Mohamedou’s “endless world tour” of detention and interrogation, as he calls it, is a journey into the heart of a global network of intelligence agencies and detention facilities that are often operating at the behest of the United States and according to unclear rules and uncertain intelligence.

For me, one of the most jarring aspects of Guantánamo Diary is the image it provides of the scope of US power and the sense you get of the breathtaking reach of that power into the lives of citizens of other supposedly sovereign states around the world: You feel how Kafkaesque our secretive national security machinery must feel in many parts of the world. It also offers one of the most riveting, humorous, maddening and ultimately devastating looks at the human drama of interrogation I’ve ever read.

Is Slahi aware of the impact that his book has had in the US and around the world?

He is, and I can only imagine how fortifying it must be to know that, after so many years of censorship and suppression, his story has literally reached around the world. At the same time, for Mohamedou, the question of impact has to be connected to the question of his continuing – as Guantánamo Diary makes clear – his obviously unjust imprisonment. Shortly after the book was published in the US and several other countries, the US government suggested he would soon receive a Periodic Review Board hearing in Guantánamo, a process that should result in Mohamedou finally being cleared for release, but seven months later there has been no PRB hearing for him, and none is currently scheduled. If Guantánamo Diary is anything, it is a straightforward appeal for justice, and I have to think that for Mohamedou, the real impact of the book will only be measured when justice is done.

How did you come to edit and write the introduction to the diary?

From 2009 to 2012, I worked with the ACLU on a project called “The Torture Report,” which involved sifting through some 140,000 pages of declassified government documents describing the abuse of prisoners in Iraq, Afghanistan, GTMO and CIA black sites – and reconstructing narratives from those heavily-redacted documents.

For GTMO, one of the narratives that emerges most clearly from the documents is the story of Mohamedou’s “Special Projects” interrogation, which is to say, his torture. And in those documents, too, were tantalizing samples of Mohamedou’s voice, in correspondence with his lawyers and particularly in the transcripts of his 2004 and 2005 review board hearings in Guantánamo.

So when his attorneys called me in 2012 and said that they had managed to get his manuscript cleared for public release, I had a pretty good idea that I would be seeing something extraordinary. In working to bring that manuscript to print, I tried in the introduction and footnotes to give readers a sense of the wealth of information that is now in the public record corroborating his account and to share a little of my own, ever-deepening appreciation for his extraordinary achievement.

Isn’t it tragically ironic that Slahi came to the attention of the US intelligence community because he waged Jihad against the USSR in a campaign that received the support of the United States government?

It is. It is one of many ironies of his case. But it’s only tragic if it results in his permanent detention, and tragic not just for Mohamedou but for us: It would say something truly awful about our capacity to understand and accurately represent our past.

In fact, I think Guantánamo Diary is more hopeful than that: I share Mohamedou’s faith in a universal sense of fairness and justice and in our ability, in the end, to get it right.

Our most important fundraising appeal of the year

December is the most critical time of year for Truthout, because our nonprofit news is funded almost entirely by individual donations from readers like you. So before you navigate away, we ask that you take just a second to support Truthout with a tax-deductible donation.

This year is a little different. We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. 2025 was a year of frightening censorship, news industry corporate consolidation, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We’ve set an ambitious target for our year-end campaign — a goal of $112,000 to keep up our fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout before December 31. If you have the means, please dig deep.