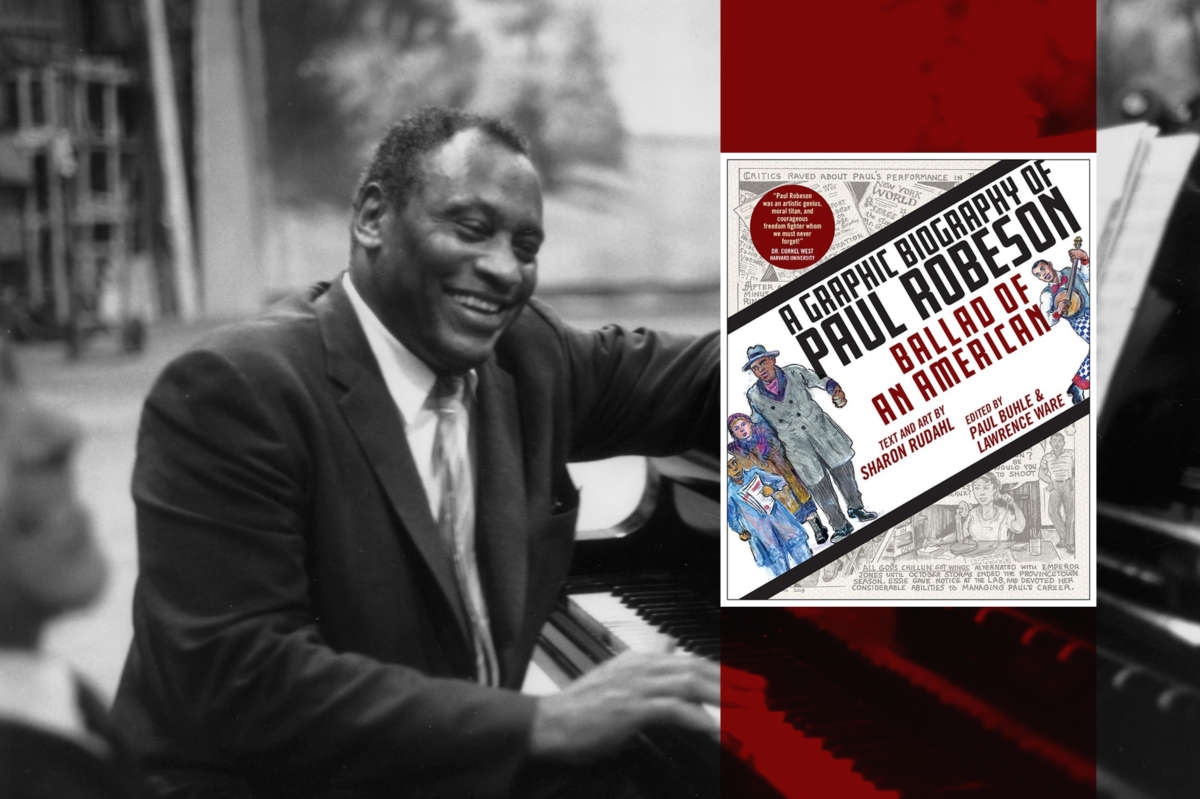

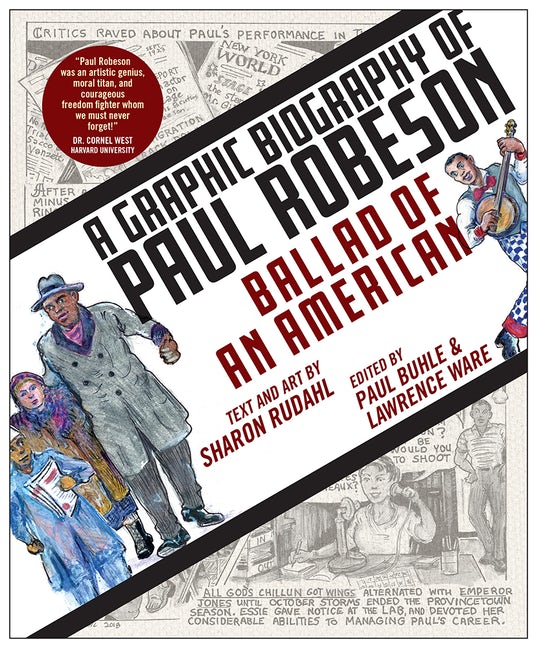

Paul Robeson, born in 1898 to a father who understood the pains of slavery firsthand, rapidly developed into a renaissance man the likes of which this nation had rarely imagined. Scholar, vocalist, athlete, actor and fearless activist, he was practically disappeared by his own government in the decades leading to his death when he was all but neutralized at age 76. This story has been told before, but never in such a visceral manner. With the latest graphic biography in the Paul Buhle pantheon, A Graphic Biography of Paul Robeson: Ballad of an American, artist and writer Sharon Rudahl (a civil rights activist, writer and political cartoonist of many years) offers the tale of Robeson to a new generation. Rudahl displays the influence of the young Paul Robeson’s father, William, who fled north to escape slavery. William fought in the Union Army and then studied at Lincoln University to become a church pastor and raise a family. His youngest child was Paul, whose life seemed to have been built of equal parts liberation, education and self-expression. Robeson’s story is not only moving, particularly when told in such a manner, but deeply inspiring to people of color, the working class and oppressed people of any race.

One gripping fact made evident in this graphic biography is that Robeson’s mother, who was legally blind, died in an accidental fire when he was but 6 years old, the flames catching onto her skirts; Robeson apparently never recalled this traumatic occurrence. The struggle continued as Rev. William Robeson was fired from his initial employment due to the incorporation of early liberation theology into his sermons. Rudahl effectively displays the young Paul’s fights for equality in New Jersey schools and Rutgers University, including the brutal attempts of white students seeking to injure him on sports fields where he was an All-American football player. His tenacity in those areas, as well as during his move into the theatre, with the lead in Simon the Cyrenian followed by Eubie Blake’s Shuffle Along and then a tour of England for another theatre work, are movingly part of this biography. And while Robeson completed his law degree and became an attorney, the racism he encountered in this profession forced him to recognize the opportunities awaiting him within a full-time career as a vocalist and actor.

From 1915, the Provincetown Players — a Greenwich Village theatre troupe founded by Eugene O’Neill, John Reed, Susan Glaspell and George Cram Cook (later additions included Edna St. Vincent Millay and Floyd Dell) — were writing and producing vitally important works of a decidedly progressive nature. Robeson soon became an actor of note within this organization, making an initial statement in O’Neill’s All God’s Chillun Got Wings and then, most famously, The Emperor Jones. These roles led to celebrity status for Robeson who then, in 1925, had a starring role in Body and Soul, a film built around Black spirituals. The experience led Robeson to focus on this music as an important African American repertoire, and he toured these songs widely, something he maintained throughout his career as he shared culture and art internationally.

Another powerful component of Robeson’s life was the role played by his wife, Essie, a writer and photographer. Even early on she was his adviser and confidant, acting as his agent for years. Rudahl displays Essie’s importance in Paul’s attaining an initial recording contract and wider stage and film roles. Robeson’s involvement in the 1920s Harlem Renaissance, and of course, his role in Hammerstein and Kern’s Showboat, are also keen points in this book.

While Robeson was an artist of the highest order, he was always aware of the racial injustice in his midst. Rudahl offers vivid details of Robeson’s maturing recognition of the machinations of racism within capitalism, starting with his Welsh tour of Showboat and his solidarity with a local miners’ strike. His commitment to international labor was maintained from that point on, often placing Robeson into a boldly activist role. More so, his studies of African heritage, the various nations and languages of the continent, allowed him to recognize the great contributions Africa brought to the world. He would, of course, make a study of various cultures, focusing ultimately on linguistics and using this skill to not only speak to the peoples he came into contact with on tour, but learn their songs as well, thereby reaching audiences on a profound level.

Much of this book is dedicated to Robeson’s political maturity and actions on behalf of the earliest civil rights movement. Also, beautifully depicted in the book is his 1934 visit to the Soviet Union following an invitation from Soviet film director Sergei Eisenstein. Rudahl tells and shows the reader how Robeson stared down and confronted Nazi guards in Berlin as he, Essie and friend Mary Seton anxiously boarded their train into Russia. Though Lenin’s great vision of the Communist revolution was already becoming torn by Stalin, the advances for the poor, people of color and women so impressed Robeson that he famously stated, “Here I am not a Negro but a human being. I walk in full human dignity.” The Robesons chose to have son Paul Jr. remain in the Soviet Union to attend school for two terms where he’d be free of racism. And by 1936, Robeson became a pivotal supporter of the left during the Spanish Civil War, traveling through war-torn areas and performing for the International Brigade wounded. During World War II, he became a major anti-fascist voice, working almost exclusively within the Popular Front and debuting “Ballad for Americans,” composed by Earl Robinson, on national radio.

At the height of his fame, Robeson lived by his ideals, refusing to perform in segregated theatres and singing a wide array of works both live and on radio, including Spanish and Chinese revolutionary material. He also took on the historic role of Othello in a smash Broadway run. Following the war, Robeson worked for Henry Wallace’s Progressive Party campaign and was a featured guest at the Paris World Peace Conference. His bold comments at the Conference, denouncing that Black people, living within institutionalized racism, were potentially drafted to fight in a segregated Army against the Soviet Union, was all of the material that the right-wing U.S. reactionaries needed in a campaign against Robeson. After being openly blacklisted on these shores, his passport was revoked, and Robeson was unable to travel for performances as his films and recordings were taken from circulation. His initial bout with major depression began in this period. Robeson was called before the brutal House Un-American Activities Committee, powerfully depicted by Rudahl, where he refused to comply, offering legendary responses to the Committee. Ultimately able to travel to Europe, he had a massive breakdown and was in London as the 1963 March on Washington occurred. Robeson desperately wanted to return home to be a part of what he had helped found decades earlier. He was largely forsaken by the younger generation of activists and, with declining health and diminishing performances, he retired and experienced a slow, sad eclipse. Robeson died in 1976.

The book concludes with a text Afterword by editors Buhle (renowned historian and author/editor of some 40 volumes) and Lawrence Ware (a professor of Africana Studies and writer on race and culture for The New York Times). This section encapsulates Robeson’s vast significance in history and offers a summary of his re-emergence in recent years, including Rutgers University dedicating a “Paul Robeson Plaza” last year. Martin Duberman’s sweeping yet equivocal biography of 1989 is acknowledged in the Afterword while also contemplating the relevance of volumes published since. More so, Buhle and Ware examine Robeson’s leading role within the Popular Front as well as the fading memory of this movement in recent decades. Happily, their depth of knowledge is imparted in this “extended scholarly footnote” for any reader unfamiliar with the Popular Front’s vital role in global anti-fascism.

The text closes with a quote by C.L.R. James, a figure Buhle has written about with passion, proclaiming Robeson as “a man of such magnificent powers and reputation (that) he gave up everything … such is the quality which signalizes a truly heroic figure.”

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.