In recent years, many films have portrayed the landscape of urban marginality and inequality in Latin America. Brazil Central Station and City of God were both popular, but few can rival the Mexican thriller, La Zona (the Zone), in depicting the disturbing panorama of inequality in Latin America’s megacities and the consequences of socially and economically divided cities.

The film is set within the confines of a gated community in Mexico. High security walls and guards encircle a hundred or so large houses with lush, evergreen gardens. The residents have their own council and make their own rules and regulations.

One night, a group of outsiders infiltrates the fencing through a domestic service entry loop. They break into a number of houses and kill one resident. A skirmish ensues between the residents and the infiltrators, and all the intruders are killed except for one, a young adolescent boy who manages to escape but is trapped within the gated community.

After some intense debate in their council meetings, the residents refuse to let the police become involved, with the consensus being that they are too corrupt to be useful. Rather, the residents decide to take matters into their own hands, and to resolve the robbery and murder themselves. The adolescent intruder – in hiding in the compound – takes refuge in the basement of a house and meets the resident’s adolescent son. An exchange occurs, and little by little, in that hiding place, they become friends.

The film is an alarming insight into urban life in Latin America – now the most urbanised continent with 80% of its population living in urban areas. In Buenos Aires, urban spaces have mushroomed in recent years – and so has inequality. According to a report of the national office of the United Nations Development Programme(UNDP), there were 90 gated communities at the beginning of the 1990s, 285 in 2001 and an estimated 541 in 2008. Middle to high-income families, who can afford the costs of running a “private city”, move to these spaces seeking to escape growing urban insecurity. If this continues, it will only increase inequality in the city and feelings of insecurity for those in gated communities.

Combatting Insecurity

Crime is a serious problem in many Latin American cities. In Argentina an independent survey has found that 86% of the population reports feelings of insecurity and more than 31% of the Argentinian population was victim of an act of violence in 2013. But rather than directly addressing youth unemployment and its attendant insecurity problems, or adequately regulating urban land and the housing market, the state has let the well-off take security into their own hands, most notably by allowing them to fence themselves off from the city.

In the meantime, the population of Buenos Aires living in informal settlements rose by 220% between 1981 and 2006, compared to a 35% growth for the urban population as a whole. These areas are typically inhabited by low-income families who cannot afford rent in the city. They occupy vacant urban land, building a dwelling from whatever material they can afford or renting what others have illegally built.

Public services are minimal; employment opportunities are mainly in the informal sector and are highly insecure; hunger and poor health are endemic. It is very often the young residents of these informal settlements who are unemployed and uneducated – and resort to drugs and crime as an easy escape – who are causing this situation of high insecurity.

Living conditions in Buenos Aires informal settlements Interdisciplinary Programme on Human Development and Social Inclusion of the Catholic University of Argentina, 2011-12

Living conditions in Buenos Aires informal settlements Interdisciplinary Programme on Human Development and Social Inclusion of the Catholic University of Argentina, 2011-12

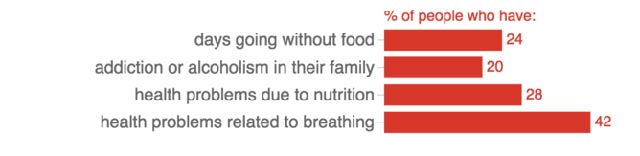

Health situation of people in informal settlements. Interdisciplinary Programme on Human Development and Social Inclusion of the Catholic University of Argentina, 2011-12

Health situation of people in informal settlements. Interdisciplinary Programme on Human Development and Social Inclusion of the Catholic University of Argentina, 2011-12

Common Ground

Everyone seeks to survive as they can. The temptation for the economically better off to relocate to gated communities and escape insecurity is great. Indeed, the slums and the gated communities are a profoundly united reality, perpetuating and reinforcing each other’s existence.

Addressing the problem of urban violence and insecurity, therefore, must be rooted in the common ground that is shared by those who enjoy the economic and social rights of the city and those who do not: their common citizenship of sharing the same physical urban space is a great place to start. In La Zona, the prejudices of the resident adolescent boy progressively diminish as he learns about the life of the intruder.

Keeping this common space of encounter is essential for survival, for as much as one group attempts to isolate itself from another, our lives are inescapably bound together. The state can play an essential role in ensuring that common spaces are preserved, but it is foremost the responsibility of all urban citizens to create spaces where collective solutions to the common problems of all inhabitants of the city can be imagined and realised.

Our most important fundraising appeal of the year

December is the most critical time of year for Truthout, because our nonprofit news is funded almost entirely by individual donations from readers like you. So before you navigate away, we ask that you take just a second to support Truthout with a tax-deductible donation.

This year is a little different. We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. 2025 was a year of frightening censorship, news industry corporate consolidation, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We’ve set an ambitious target for our year-end campaign — a goal of $125,000 to keep up our fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout before December 31. If you have the means, please dig deep.