Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

A recent New York Times article detailed the ways California as a state has become the Trump administration’s bête noire. According to reporter Tim Arango, the morning after Trump was elected, “Kevin de León, the State Senate leader, and his counterpart in the Assembly, Anthony Rendon, said they ‘woke up feeling like strangers in a foreign land.'”

In the past year, California has declared itself a sanctuary state. It raised the minimum wage and expanded worker protections. It legalized recreational marijuana. Legislators declared they would not permit offshore oil drilling. They proposed making state taxes charitable contributions to keep them deductible with the IRS.

It might seem strange to activists under 40 to think that Los Angeles was the “citadel of the open shop” for almost a century. That the city that elected Rendon and De Leon had as mayor a conservative ally of President Nixon — Sam Yorty — and the country’s most active and violent police “red squad.” That Berkeley sent an extreme right-winger into the legislature who headed up California’s own “Un-American Activities Committee.” That the state was ruled by agribusiness with an iron hand, and farm workers who went on strike were beaten and murdered.

Arango credits California’s rebellion to its racial diversity and growing Latino population. There’s no doubt that state Republicans sealed their unpopularity in the days of Gov. Pete Wilson two decades ago. Their campaign for Proposition 187, which would have denied education and hospital care to the undocumented, convinced hundreds of thousands of immigrants to apply for citizenship just to be able to vote against the juggernaut.

But there’s another good reason for the state’s current politics: unions.

California has 2.55 million union members, more than any other state, more even than all the jobs in Minnesota. Runners-up New York has 1.9 million and Illinois has 812,000. About 15.9 percent of California workers belong to unions — unchanged for the last few years. Because of its large population and workforce, it doesn’t have the highest density — New York (23.6 percent), Hawaii (19.9 percent), Alaska (18.5 percent), Connecticut (17.5 percent) and Washington State (17.4 percent) have a greater percentage of union workers.

But the state’s labor movement has been able to translate its membership into a solid voting base, which has made these political changes possible.

Members of the San Francisco hotel union, Unite Here Local 2, march in support of undocumented immigrants in a Labor Day march in 2006. (Photo: David Bacon)

Members of the San Francisco hotel union, Unite Here Local 2, march in support of undocumented immigrants in a Labor Day march in 2006. (Photo: David Bacon)

How California got from one place to the other is an important story. It’s not just that we’re faced with a political onslaught that wants to return to what California looked like a hundred years ago; we need to know how we got here, and what lessons we can draw from this experience.

That’s the knowledge that Fred Glass gives us in From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement (University of California Press, 2016). Glass helped found the Labor in the Schools Committee of the California Labor Federation two decades ago. He then produced Golden Lands, Working Hands, which has become the basic resource for educators introducing class concepts into classroom curricula. His new book is based on the research he did for the video, and on the lessons learned in using it.

The book’s title is too limiting, I think. You can’t look at the history of unions and working-class struggle in California as something isolated from the broad social movements that have changed the state, and the book is a deep and entertaining examination of that relationship.

Glass sees racism, discrimination against women and anti-immigrant pogroms as the fundamental social barriers that had to be fought in order for a progressive change to take place. Strikes, organizing drives and political mobilizations, he shows, all took place within this broader context.

In looking at the role of immigrants, he notes,

The demographic trend by which immigrant workers have fueled California’s population increases will continue, in California and increasingly in other states. The high proportion of immigrants who come to this land to work ensures that a sizeable number will bring along familiarity with, and often sympathies for, the goals of organized labor. In some cases, that will include histories of union involvement … young workers of color, including a high proportion of immigrants, are the future face of the workforce and the electorate. Because the labor movement has understood this fact and designed its efforts around it, California’s unionization rate remains at 16 percent while the national average is 11 percent.

Glass begins his examination with the original inhabitants and workers of California: the Indigenous peoples who were enslaved by the Spanish missions, and then “produced the surplus agricultural products” that supplied the military stockades and the beginning of foreign trade. It is an important point, not just because he shows, as does Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz in her work, the ghastly cost to Indigenous communities of Spanish and Mexican colonization, but because he sees in class terms the basic operation of the system: the production of value, and its expropriation by those with power. This class framework continues throughout the book.

Class conflict is, of course, part of the history of the United States and its capitalist system. The primitive accumulation of capital in California wasn’t based on the chattel slavery of Africans, as it was in the US South. In fact, one of the most important fights as California was incorporated as a state in 1850 was to keep the slavers from expanding into its territory. Instead, the heaviest price was paid first by Native people, and then by the Mexican and Chinese population.

California became a state because of the gold fever, and Glass tells the story of gold’s “discovery” at Sutter’s Fort, and documents the terrible conditions for miners as they came pouring in. Yet the first miners were the Mexicans, who earlier traveled north from Sonora. They then found themselves foreigners in their own land after California and other states were taken from Mexico in the war of 1848. A guerilla war raged for several years, as those miners fought to keep their claims. The names of the many people hung in the gold fields were all Spanish, and California’s first law was the foreign miner’s tax act, intended to dispossess the Sonoran miners.

Glass balances his respect for the way workers then organized themselves over the following decades with a careful account of the attacks, especially on Chinese workers brought to build railroads and drain river deltas. He tells the story of the first teacher activist, and an early woman labor leader, Kate Kennedy, and the birth of the first unions — for typographers, teamsters and carpenters.

Alexander Kenaday, founder of the typographical union, organized San Francisco’s first labor council, and began the fight to get the eight-hour day in 1865, when the Civil War wasn’t yet over. A long fight it’s been. This year, California’s legislature finally passed a bill giving farm workers and domestic workers overtime after eight hours — people excluded from laws passed even at labor’s moments of greatest strength. California is still the only state (except Hawaii) that has such a law for farm workers, and one of only a handful with a Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights.

Members of the janitors union, United Service Workers West, sit down in a downtown Los Angeles intersection in 2011, to protest the firing of immigrant workers. (Photo: David Bacon)

Members of the janitors union, United Service Workers West, sit down in a downtown Los Angeles intersection in 2011, to protest the firing of immigrant workers. (Photo: David Bacon)

In tracing California workers’ and unions’ long movement toward racial unity, a movement far from complete, Glass pays particular attention to one of the most important and formative efforts: when workers harvesting sugar beets in Oxnard organized the Japanese Mexican Labor Association and struck in 1903. They applied to affiliate their organization with the American Federation of Labor (AFL), and AFL President Samuel Gompers refused a charter because their union included Japanese workers. The head of the Mexican workers, J.M. Lizarras, supported by Socialist leaders of the Los Angeles Labor Council, replied, “We would be false to them and to ourselves and to the cause of unionism if we accepted privileges for ourselves which are not accorded to them.”

Glass notes the role the Mexican anarcho-syndicalist brothers Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magón played in the growing Los Angeles labor movement. When they sought to build the Liberal Party to overthrow Mexican dictator Porfirio Diaz, LA’s labor movement mounted their legal defense. The book makes plain that debates over the role of Mexican immigrant activists in the US and the need for cross-border solidarity were going on almost a century before NAFTA went into effect.

Glass covers the seminal events in the labor movement’s growth, and in the debates over its tactics and political direction: the bombing of the LA Times (now in the midst of another union organizing drive), the rise of the IWW in the state’s fields, the first unions in Hollywood, and finally, the great debate over industrial unionism in the wake of the Depression.

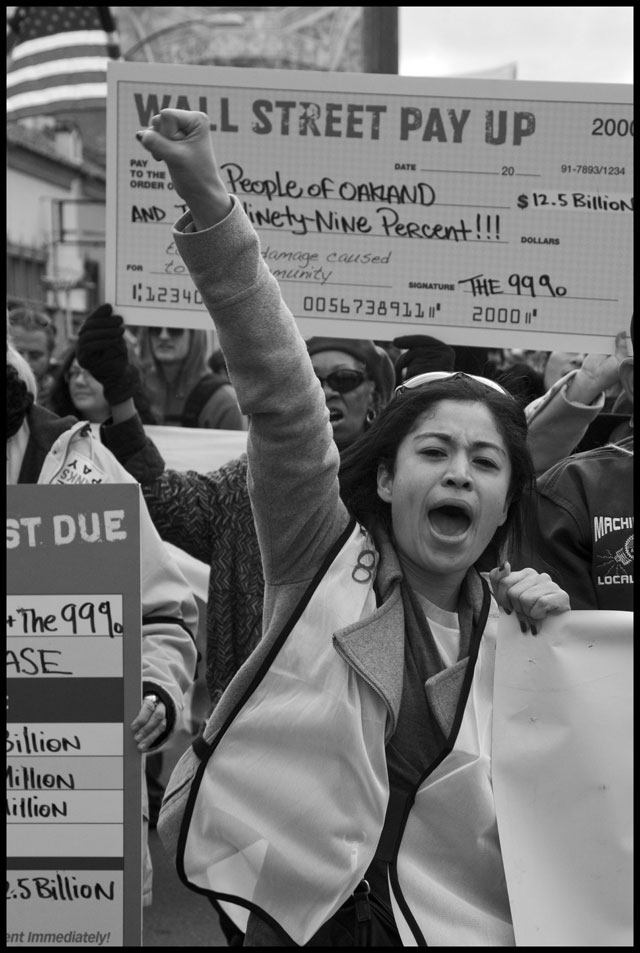

During Occupy Oakland in 2011, the unions of the Alameda County Labor Council organized a march in support of Occupy. (Photo: David Bacon)

During Occupy Oakland in 2011, the unions of the Alameda County Labor Council organized a march in support of Occupy. (Photo: David Bacon)

From Missions to Microchip doesn’t just cover events, it describes the politics and political organizations of labor’s activists and organizers, especially on the left. Communists organized the great strikes in the fields. Los Angeles’s garment workers were organized by Socialists.

This complete way of telling labor’s story is most important in recounting its two watershed political moments. Glass gives readers the San Francisco General Strike in detail, and the role of left-wing organizers, especially Communist workers, is clear. An organized left, and the struggles and debates it provoked, prepared the ground for the fight for unions along the waterfront, the rise of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (one of the country’s most progressive), and the consolidation of the CIO [Congress of Industrial Organizations] on the West Coast. San Francisco became a labor town, and has stayed a labor town, because of that conflict. In the middle of that strike, longshore leaders forged an alliance with the city’s Black communities to end discrimination on the docks. ILWU Local 10 is a majority-Black union today as a consequence.

The other experience that shaped California unions, as it did labor throughout the country, was the Cold War. The story of The Hollywood Ten is, after all, a labor story. The Cold War and its blacklists followed, by no coincidence, the strikes to win unions in Hollywood, and eventually propelled Ronald Reagan into the White House. The expulsion of the left, and purge of Communist, Socialist and left-wing workers and leaders in the Cold War weakened unions across the country. California unions survived better than they did in many places. Although the ILWU was expelled from the CIO because of its Communist and left-wing history, it had consolidated control over the waterfront to such a degree that it couldn’t be dislodged, and helped keep progressive politics alive in West coast cities.

Glass pays a lot of attention to the long history of farm worker unions, and makes it plain that the United Farm Workers (UFW) didn’t rise from nowhere, but called on the experience that Filipino, Mexican, Black and white workers gained in organizing and strikes over previous decades.

Labor activists still debate many of the questions around the life of the UFW. Today we see the growth of guest-worker programs again, much like the bracero program whose end in 1964 set the stage for the great Delano Grape Strike of 1965. California’s Supreme Court just upheld part of the state’s farm worker labor law that requires the mandatory mediation of first-time contracts, the only law of its kind and one that most unions would kill for. The union itself is still active, but has far fewer members than it did at its height at the end of the 1970s. From Mission to Microchip describes the history and notes the debates, leaving it to the activist to plunge into them by reading further.

Finally, Glass takes the reader through the rebuilding process coming out of the Cold War: the organization of teachers (his own union) and other public employees, health care workers, janitors and drywalleros. The changing politics of Los Angeles, it makes clear, came as a result of the rise of Justice for Janitors, the hotel workers union UNITE HERE Local 11, and the organization of workers’ centers among immigrants, women and workers of color.

With a history so filled with contention and debate, strikes and their violent repression, and conflict over racism and left-wing politics, it might be counterintuitive to think that California’s labor movement would emerge strong and progressive. Yet this is what happened. From Mission to Microchip tells the story. Perhaps the lesson here is that left-wing politics, debate and class conflict are not harmful to workers and unions, but in fact the very things that help them find direction and organize.

That is a lesson that deserves to be in the classrooms where the children of working-class families lay claim to their own history.

An urgent appeal for your support: 10 Days to raise $50,000

Truthout relies on individual donations to publish independent journalism, free from political and corporate influence. In fact, we’re almost entirely funded by readers like you.

Unfortunately, donations are down. At a moment when independent journalism is urgently needed, we are struggling to meet our operational costs due to increasing political censorship.

Truthout may end this month in the red without additional help, so we’ve launched a fundraiser. We have 10 days to hit our $50,000 goal. Please make a tax-deductible one-time or monthly donation if you can.