“Don’t buy pork” imported from Mexico, implores Renato Romero, a Mexican farmer who is leading a resistance effort against the transnational company Smithfield Foods, which is headquartered in Virginia but runs hog farms and processing plants in Mexico.

In June, state security forces in Mexico killed two members of a farmer-led movement resisting the giant pork producer, which has left local farmers without water and contaminated the land.

Other members of the movement have received death threats and court summonses.

Romero’s call comes as climate scientist Claudia Sheinbaum prepares to take office as Mexico’s president on October 1. Despite her qualifications, many movements and analysts see her and her party Morena’s potential impact on the environment as palliative at most. Limited by corruption in her party, organized crime and a track record of prioritizing corporations over people and planet, Sheinbaum is unlikely to challenge the international and local economic forces holding the environment hostage.

Adapting to Crises

In Mexico, about 75 percent of lakes and rivers are contaminated with substances that can cause serious illness. Authorities have identified 30 “environmental hell” regions where illness and death rates are spiking as a result of toxic residues, pesticides, and other industrial contamination. Only 18 percent of homes in these regions have a regular, daily water supply, while corporations are given permits to exploit huge quantities of water.

Outgoing President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO) and Morena have done very little to address such issues. In Puebla, for example, the Morena-led congress did not deprivatize water, and instead, passed fee increases.

“In all these years, we’ve seen that the government doesn’t care about our land or Indigenous communities, and the only thing they care about is money and mega construction projects,” Anselma Margarito, an Otomí Indigenous activist leader, told Truthout.

Sheinbaum, in her 100-step plan, only dedicates a few pages of the 381-page document to the environment. Her key policies are building strategic infrastructure, employing technology for the efficient use of water on farms, and using treated water instead of first-use water in cities. The plan even states that “the hoarding of water through permits sold through an unregulated market should operate within the law.” There is nothing concrete in the plan for preventing contamination, cleaning rivers, or stopping the harm by large industries.

Wilfrido Gómez Arias, a Mexico City-based academic investigating Mexico’s water permit system, told Truthout that Sheinbaum has no answers to climate change and described her approach to the environment as “management and technification … but ultimately (the government) sees water as merchandise.”

The Morena government “only redirects the problem a little bit … It uses palliative measures. Maybe they will use technology to improve the water quality, but they won’t touch the major [corporate] users of water, because the economic interests are extremely strong. You need water to do everything … the stealing of water will continue,” he said.

Efraín Morales López, head of Sheinbaum’s National Water Commission (Conagua), and other media spokespeople for Conagua did not reply to requests for comment.

“Access to water will be a priority for our government,” Sheinbaum said during her election campaigning, promising to “revise” and “regulate” the water permits that have been granted to corporations.

Largest Pork Company in the World Is Targeting and Killing Protesters

Meanwhile, people on the front lines of environmental defense face serious repression.

“I’ve been a beekeeper my whole life and when Granjas Carroll [a subsidiary of Smithfield] was set up, my bees started to die. I changed out the queens, I changed the boxes. But it turns out the sheep were dying too. And my honey was contaminated with sulfonamides,” Moisés Moratilla told Truthout. Sulfonamides are used as antibiotics for pigs. Moratilla is an independent beekeeper in Tepeyahualco, Puebla, near various farms and factories operated by Smithfield. Along with Romero, he’s a leader of the Movement in Defense of Water in the Libres-Oriental Basin, which has been resisting the company.

Smithfield Foods, a U.S. company, has a controlling interest in Granjas Carroll, which operates 140 sites across Mexico, including hog farms, feed production and pork processing. Smithfield is in turn owned by WH Group, the largest pork company in the world.

Moratilla has struggled to sell his honey since 2017, when a distributor rejected it because it contained antibiotics and pig feces. Further, the expansion of Granjas Carroll saw a reduction in the bee foraging range. Farmers accuse the company of contaminating the water table and hoarding water, leaving them without.

The company is also trying to control small farmers and stop them from producing corn in order to dominate the market for pig feed, Moratilla said, adding, “There is a food chain, and they want to eliminate small farms; that no one eats what they produce themselves, everyone has to go and buy from Granjas Carroll.” Romero also told Truthout that the company prohibits its workers from having pigs on their own farms.

Their movement is demanding the company leave the region and that other transnationals in the region stop stealing their water. As a result, Moratilla said he has been receiving death threats since May, by phone and in person “as an attempt to stop the protests against the company.” He said government officials threatened him, “Do you know that I can make you all disappear, that I can put you in jail right now?” On June 12, Moratilla’s two children were shot at, beaten up, and their motorbike and phones stolen. On June 14, he was threatened again that if he didn’t leave the movement, he would be killed, with the caller saying, “look what we did to your children.”

“It seems that Granjas Carroll is determined to put us in jail,” Romero told Truthout after receiving a third court summons earlier this month.

On June 20, over 300 common landholders were repressed after blocking a main road to Granjas Carroll, with security forces shooting and killing two people.

“Meat from Granjas Carroll is stained with our blood … this business is linked to crimes against the people,” said Romero, stressing that the National Guard didn’t do anything that day to stop the repression or shooting.

“They [Morena’s administration] say they put the poor first, but … they are defending the companies and building roads,” Moratilla said, noting the government has built roads for Granjas Carroll, while also passing a law making the movement’s road blocks illegal.

According to Romero, other companies in the region, including Heineken, Iberdrola, Audi, and transnational berry companies “have so much land. They harvest and send the products north [to the U.S.]. They use a lot of water, and then their discharge is contaminated. The institutions that should be monitoring that, don’t. Business is more important than laws for them.”

Free Pass for Corporations

After winning the election in June, Sheinbaum has prioritized meeting with big businesses. A few days after the election she met with the Mexican general director of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, saying the company is “committed and enthusiastic about increasing the number of investment projects in Mexico.” She has also touted her meeting with HSBC about investments, among other companies.

Mexico rose from the ninth largest food exporter globally in 2022, to the seventh largest in 2023. Such exports are facilitated by free trade agreements like the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (the successor to NAFTA), exploitative wages and water access. “Transnationals come here because the laws are weaker,” argued Gómez.

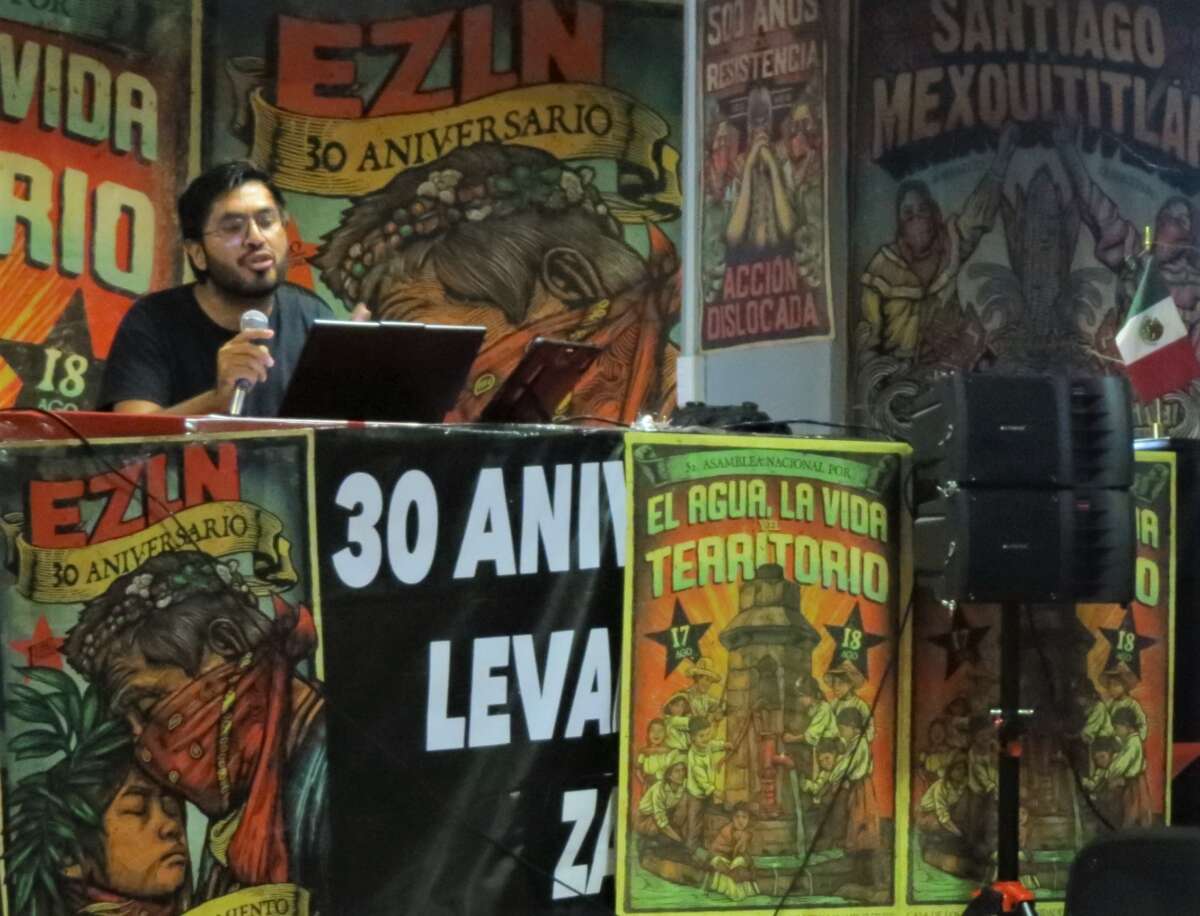

“(National and local) governments have promoted capitalist agriculture and agribusiness … the large landholders benefit from water permits and subsidies for buying machinery and irrigation technology,” said Romero at a press conference attended by Truthout in July.

As part of the signing of NAFTA with the U.S. and Canada in 1992, Mexico was required to pass a national water law that same year. That law provided a framework for Conagua, which from then until 2020 had issued over 514,000 water permits, effectively privatizing that water, in what many have labeled a “water market.” This led to huge inequalities in water distribution. In her 100-step plan, Sheinbaum says she will strengthen Conagua so that it can better fulfill its political, technical and financial duties.

The movement resisting Granjas Carroll, on the other hand, accuses Conagua of being “mired in corruption” because it gives out permits to corporations but not to Indigenous and common land owners and small farmers. In August, water activist Elena Burns told La Jornada she was surprised that Conagua had awarded permits to Granjas Carroll, given the water shortages in the region.

According to Gómez’s research, U.S. transnational Kimberly-Clark has permits worth 27.3 hm³ per year (27 billion liters of water). Coca Cola Femsa, with permits worth 39.4 hm³, has been denounced for over-exploiting aquifers in Chiapas and Tlaxcala and leaving locals without water; and the tourism real estate venture El Coyote Baja Resort has permits worth 90 percent of the nearby aquifer. He found that there are 3,304 “water millionaires” — entities with permits worth 1 hm³ per year or more, and that just 1 percent of water users occupy over a quarter of the country’s water resources.

“It’s a huge inequality; the concessions are going to those with the most economic power, who can use lawyers and apply pressure,” he told Truthout.

Further, less than 3 percent of the companies are paying the required water-use fees, his study found. And Conagua itself admits that it is short some 80 percent of taxes, receiving only 12 billion pesos in 2024, when it should have received at least 55 billion. This money, Burns points out, has gone into the pocks of transnationals and agribusiness, instead of being used on water infrastructure.

Movements and Organized Communities Are the Only Ones Stopping Corporations

Farmers, residents of poorer communities, and Indigenous peoples are disproportionately affected by contaminated water, drought and shortages — and so it is those people who are doing the most to protect the environment.

Recently, after a five-month long blockade, Puebla Nahua communities managed to shut down a private waste dump that was contaminating the water table. It was also years of organizing by Indigenous communities in the Sierra Norte mountains of Puebla that shut down a Canadian mine owned by Almaden. Likewise, it was locals who shut down U.S. beer manufacturer Constellation Brands in Mexicali, after it was found hoarding water. The Morena government then relocated it to Veracruz.

In August, farmers, movements and Indigenous communities from across the country met in Mexico City in the Fifth National Assembly for Water and Life to discuss joint strategies to defend the environment. Some 1,000 people participated, including from Ñhöñhö, Purépecha, Mixe, Mayo, Wixarika, Yoreme, Nahua, Yaqui, Mazateca, Mixteca, Totonaco, Popoluca, Nuu Savi, Maya, Tepehuano, Guarijío, Rarámuri, Nayeri, Tzeltal, Tololabal, Zapoteco, Tohono Odam and Bini Zaa Indigenous communities. Organizations, such as the National Indigenous Council (CNI), the Supreme Indigenous Council of Michoacan, the Union of Indigenous Communities of the Northern Zone of the Istmo, the vendors’ union in Puebla 28 de Octubre, and 260 other groups were present.

In this assembly, “we are letting the government know that we are sick of them taking our water and selling it to the soda and beer companies…. The communities are united and we are the rock in the shoe that will never leave them (companies and government) in peace,” said Margarito.

She was recently detained by police after hired thugs attacked a protest she was attending against the criminalization of a fellow water rights activist. Margarito and others were beaten and charged, but the thugs were not. She said that despite such “repression, imprisonments, forced disappearances, we are still here. We’re going to stay united in order to confront these problems.”

Help us Prepare for Trump’s Day One

Trump is busy getting ready for Day One of his presidency – but so is Truthout.

Trump has made it no secret that he is planning a demolition-style attack on both specific communities and democracy as a whole, beginning on his first day in office. With over 25 executive orders and directives queued up for January 20, he’s promised to “launch the largest deportation program in American history,” roll back anti-discrimination protections for transgender students, and implement a “drill, drill, drill” approach to ramp up oil and gas extraction.

Organizations like Truthout are also being threatened by legislation like HR 9495, the “nonprofit killer bill” that would allow the Treasury Secretary to declare any nonprofit a “terrorist-supporting organization” and strip its tax-exempt status without due process. Progressive media like Truthout that has courageously focused on reporting on Israel’s genocide in Gaza are in the bill’s crosshairs.

As journalists, we have a responsibility to look at hard realities and communicate them to you. We hope that you, like us, can use this information to prepare for what’s to come.

And if you feel uncertain about what to do in the face of a second Trump administration, we invite you to be an indispensable part of Truthout’s preparations.

In addition to covering the widespread onslaught of draconian policy, we’re shoring up our resources for what might come next for progressive media: bad-faith lawsuits from far-right ghouls, legislation that seeks to strip us of our ability to receive tax-deductible donations, and further throttling of our reach on social media platforms owned by Trump’s sycophants.

We’re preparing right now for Trump’s Day One: building a brave coalition of movement media; reaching out to the activists, academics, and thinkers we trust to shine a light on the inner workings of authoritarianism; and planning to use journalism as a tool to equip movements to protect the people, lands, and principles most vulnerable to Trump’s destruction.

We urgently need your help to prepare. As you know, our December fundraiser is our most important of the year and will determine the scale of work we’ll be able to do in 2025. We’ve set two goals: to raise $150,000 in one-time donations and to add 1,500 new monthly donors by midnight on December 31.

Today, we’re asking all of our readers to start a monthly donation or make a one-time donation – as a commitment to stand with us on day one of Trump’s presidency, and every day after that, as we produce journalism that combats authoritarianism, censorship, injustice, and misinformation. You’re an essential part of our future – please join the movement by making a tax-deductible donation today.

If you have the means to make a substantial gift, please dig deep during this critical time!

With gratitude and resolve,

Maya, Negin, Saima, and Ziggy