Part of the Series

Beyond the Sound Bites: Election 2016

For the Republican presidential candidates, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has been a sort of collective punching bag. Every single candidate wants a repeal of the health-care law, which was a stinging victory for President Obama and the Democrats. Donald Trump would replace it with something vague and “terrific.” Sen. Ted Cruz essentially foreshadowed his candidacy by shutting down the government over the ACA. Sen. Marco Rubio has called it “fatally flawed.”

Health care is certain to be one of the most partisan debates of the upcoming election, and even Democrats are arguing over the issue now that Bernie Sanders has unveiled his single-payer “Medicare for All” proposal.

What we haven’t heard in the presidential debates is that the ACA – or a universal, single-payer health-care system – is crucial for combatting HIV/AIDS. Activists and public health experts agree that people living with HIV or at risk of contracting the virus are already benefiting from the ACA, which provides crucial pieces to the puzzle of fighting HIV/AIDS across the population.

The United States has come a long way since the early days of HIV/AIDS, but the epidemic is far from over. In medicine, stigma has largely been replaced by science, and today no mainstream politician in their right mind would say they support anything but ending HIV/AIDS. In politics, however, facts are known to disappear in clouds of rhetoric and emotion. Many politicians routinely oppose public health policies that experts say are necessary to reduce the number of new infections, even when these policies could save billions of dollars in medical costs and untold numbers of lives.

To understand how this works, consider Medicaid and its expansion under the ACA. Medicaid was already the largest provider of medical coverage for people living with HIV even before eligibility was expanded in the 32 states that have allowed it, providing thousands of low-income people with access to medical care and drugs to suppress the virus. When the virus is suppressed, it’s less likely to be transmitted to others.

“There is no way for us to do the work to end the HIV epidemic in the United States that does not involve Medicaid or another public insurance program that is widely available to people,” said Kenyon Farrow, a policy director at the Treatment Action Group.

The ACA also made it illegal to deny or drop insurance coverage due to a pre-existing condition such as HIV, making it easier for people living with HIV to find and afford private insurance plans.

“We can’t just test and treat our way out of the epidemic. We have to have engagement in health care to reduce rates.”

Access to medical care is a major factor in reducing HIV viral loads and transmission rates. And modern anti-retroviral treatments are so effective that some people living with HIV are “undetectable,” meaning their viral count is virtually zero because they are on medication. For those who are HIV negative but at risk of contracting the virus, a relatively new drug known as PrEP has proved to be effective at preventing infection.

With these drugs on the market, activists and medical experts see a light at the end of the HIV tunnel, but the drugs can’t stomp out HIV if people can’t afford them.

Jennifer Kates, the director of global health and HIV policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation, said that many lower-income people living with HIV were caught in a dangerous “catch-22” before the ACA made Medicaid available to more people. Simply being poor wasn’t enough to qualify for Medicaid; applicants also had to have children or be disabled. Many people living with HIV were not considered “disabled” until their illness progressed to AIDS, which can be fatal.

“So, you can’t get the medications that prevent you from becoming disabled until you become disabled – that didn’t make sense,” Kates told Truthout.

The Right to See a Good Doctor

Ending HIV requires more than medication, according to Farrow. To begin with, people need basic primary health care. Poor and marginalized people face barriers, ranging from cost and social stigma to discrimination at the hands of providers. These barriers prevent them from receiving basic checkups that can identify health problems like HIV early.

Of course, this lack of primary care affects many people beyond undiagnosed patients themselves: HIV is more likely to spread if it remains untreated or undiagnosed, and Farrow said those at risk need to establish relationships with knowledgeable doctors in order to have regular checkups and discuss prevention strategies like PrEP. This can make a huge difference, particularly for at-risk populations such as low-income transgender women and homeless LGBTQ youth that are often excluded from health care due to their identities and financial situations.

“We can’t just test and treat our way out of the epidemic,” Farrow said. “We have to have engagement in health care to reduce rates.”

Stigma, homophobia and discrimination put gay, bisexual and queer men of color at risk of mental and physical problems that may affect whether they are able to receive quality preventative health care, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Health-care inequality has contributed to disproportionate rates of HIV among people of color and transgender women, especially those who have experienced job discrimination, homelessness and incarceration. The most recent data is devastating.

Last month, the CDC estimated that 50 percent of Black men who have sex with men and 25 percent of Hispanic men who have sex with men would contract HIV in their lifetime if current rates of infection continue. Less then 10 percent of gay, bi and queer white men are expected to contract the virus during their lifetimes.

The Human Rights Campaign reports that the HIV rate among transgender women is 49 times the national average. Studies show that transgender people who have faced job discrimination or harassment at school are more likely to engage in sex work to survive, and the CDC has found more than half of transgender women diagnosed with HIV in New York City experienced hardships associated with criminalization such as homelessness, assault and incarceration. Many are denied health care due to their gender identity or report harassment at the doctor’s office, which can be a deterrent to showing up in the first place, especially if they can only afford certain providers.

“Creating that base of people having at least that basic care via Medicaid would go a long way to alleviate those problems,” Farrow said.

Republicans Block Medicaid in States Hard-Hit by HIV

The ACA has started to address health-care disparities by providing millions of people with coverage options. Low-income people living with HIV who have relied solely on federally funded HIV specialty clinics for health care can now see different doctors for other conditions. (Kates said the specialty clinics remain a crucial resource, however, especially in states that have blocked Medicaid expansion.)

A single-payer system could have further benefits for people living with HIV. Under Canada’s single-payer system, for example, the province of British Columbia has decided to pay for all HIV medications, and seeing a doctor is free, according to M-J Milloy, a research scientist at the British Columbia Center for Excellence in HIV/AIDS.

“[Getting HIV] medication is simply a conversation between you and your doctor,” Milloy said. “It’s really distressing when us scientists hear of these places where there are still these economic and financial barriers to HIV medication because we are hearing more and more everyday that the way to end AIDS is to provide the medicine.”

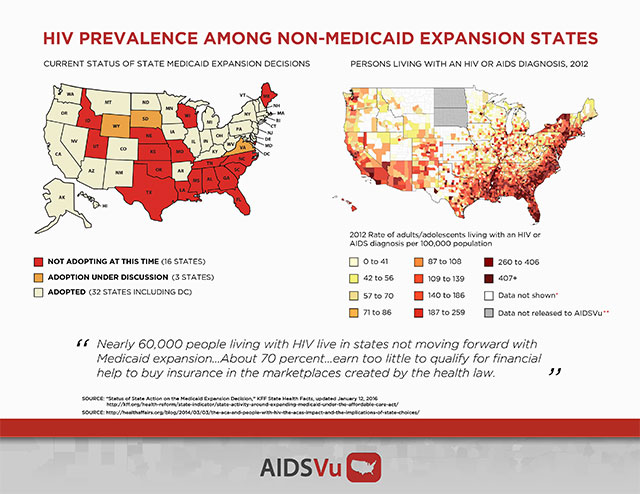

That’s exactly why advocates like Farrow are so frustrated by Republican efforts to block the ACA’s Medicaid expansion at the state level by refusing to expand the minimum Medicaid eligibility to 133 percent of the federal poverty line and accepting the federal dollars that come with it. Many of the 16 states that have so far failed to expand Medicaid rolls also have high rates of poverty and large numbers of people living with HIV and AIDS.

A 2014 study found that more than half of the 115,000 uninsured, low-income people living with HIV live in states that blocked expansion. Another 2014 study co-authored by Kates found that the number of people eligible to use Medicaid to pay for HIV treatments dropped by 43 percent because only 26 states agreed to expansion at the time. Many found themselves in a “coverage gap”: They were too poor to qualify for subsidies in the Marketplace but not poor enough for Medicaid.

The coverage gap primarily affects people of color. In Georgia, 74 percent of the estimated 305,000 people in the coverage gap are people of color, according to Kaiser Family Foundation data. In Alabama, that number is 46 percent even though people of color only make up about 34 percent of the population. In Florida, which has the nation’s highest rate of death among Black people with an HIV diagnosis outside of Washington, DC, people of color make up 57 percent of the 567,000 in the coverage gap.

In the Deep South, where so far every state has yet to expand Medicaid rolls, nearly 60 percent of people living with HIV are Black, according to AIDSVu, an HIV/AIDS data and mapping service. Nationally, Black people account for 44 percent of new infections, but in Georgia, Texas, Louisiana and Florida that number is 65 percent or higher.

These numbers are alarming, but don’t expect them to appear on the mainstream political radar anytime soon. Some politicians may not be paying attention, but others appear willfully ignorant. Consider former Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal, a Republican who boasted about rejecting Medicaid expansion and the federal dollars that come with it during his failed presidential bid, even as Louisiana and its hospital system faced a looming budget crisis.

In 2015, Jindal even attempted to cut Planned Parenthood off from state Medicaid payments due to the faux controversy over alleged fetal tissue sales. The state’s two clinics do not provide abortions, but they do provide reproductive health care to about 5,200 people in and around New Orleans and Baton Rouge – two cities with some of the highest HIV infection rates in the nation.

Planned Parenthood convinced a federal court to block Jindal’s move, and the ensuing legal battle was widely seen as an expensive campaign stunt, strategically timed in concurrence with Jindal’s presidential run. By the time he dropped out of the race, Jindal’s home state approval ratings were in the gutter. Voters in the deeply red state elected a Democrat, Gov. John Bel Edwards, to replace him. Edwards plans to expand Medicaid rolls in June, but he also campaigned on his anti-choice record and recently handed the federal appeal against Planned Parenthood over to the state attorney general instead of dropping the case.

Farrow said HIV advocates cannot assume that other red states will follow Louisiana’s lead and oust ACA opponents any time soon, and there should have been more outrage over the 2012 Supreme Court decision that made Medicaid expansion optional. In Kentucky, for example, a newly elected Republican governor is already working to roll back Medicaid expansion. Reformers in Washington, DC, seem content to let the dominos slowly fall; after all, it’s politically unsustainable to give people a federal benefit in some states and not others. But Farrow said people who are living with HIV or are at a high risk of contracting it can’t afford to wait, and in general, providing low-income people with health-care access makes society healthier as a whole.

Kates said that a growing number of politicians are realizing that access to HIV medications is a “critical public health intervention,” especially when they look at the bottom line.

Cost estimates of treating an HIV infection over a lifetime range from $380,000 to $435,200, and providing people with basic health care and prevention is much cheaper than providing post-diagnosis treatment. Recent analysis by the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine found that $96 billion in improvements to HIV-related health care would reduce new infections by 54 percent, saving the national health-care system about $256 billion over the next two decades. If you’re a fiscal conservative, what’s not to like?

A Nonprofit Model for the Rest of the Country

Sometimes you have to spend money to save money, and both Kates and Farrow pointed to New York, a state that has been hard-hit by HIV since the beginning of the epidemic. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo recently announced $200 million in funding for HIV-related housing and medical services over the next five years, an 8 percent increase in the $2.5 billion the state already spends annually.

The funding is part of Cuomo’s “blueprint for ending the epidemic” – but don’t give his administration all the credit. Advocates say the Cuomo administration’s plan to “end HIV” by 2020 is the result of tireless grassroots advocacy

Doug Wirth is the CEO of Amida Care, a nonprofit health plan in New York City that is specifically tailored to Medicare and Medicaid recipients living with HIV. He also serves on Cuomo’s “end the epidemic” task force, and has spent years taking grassroots concerns to New York’s most powerful leaders.

“One of the fundamental differences about [Amida Care] is how we got our start; we were started by community based organizations, not hospitals or people with for-profit motives,” Wirth told Truthout. “That’s at the heart of who we are and it keeps us to this mission, making sure that we improve the lives of people living with HIV.”

Wirth said that in the 1990s, housing and HIV advocates began raising red flags as former Gov. Mario Cuomo moved to advance Medicaid. Many Medicaid plans did not have HIV providers in their networks and could not meet the needs of people living with chronic conditions such as HIV. The payment system for providers caused delays, and people with emergent HIV infections were not seeing specialists fast enough.

Instead of waiting for general and commercial plans to develop HIV expertise, lawmakers and advocates agreed that community groups should develop special coverage plans for people with HIV. Amida Care is one of three plans now available in New York, each one created by activist efforts uniquely in tune with the needs of the HIV community. Amida Care now has 6,000 members. The majority are people of color, and 7 percent are transgender women. Ninety percent are receiving ongoing, sustained medical care.

“We increased the amount of money we spent on the outpatient side: primary care, mental health services, addiction services, case management, and since 2008 we’ve been able to reduce emergency room visits by 64 percent and reduce hospital admissions – we’ve reduced that over 70 percent,” Wirth told Truthout. “And the way that we’ve reduced is we made sure that people got primary care and medication and behavioral health support so they could be adherent [to drug regimens].”

In all, Wirth said, viral suppression among Amida Care’s members is approaching 75 percent, and the special needs plan has already saved New York’s Medicaid system $88 million. That’s because Amida Care doesn’t just provide checkups and prescriptions; they actually listen to their members to learn about their needs.

“One of the things that our members told us is that, ‘We want you to do more than tell us to go to the doctor’s office and take our pills on time,'” Wirth said.

So, Amida Care began providing new kinds of wellness programs – African dancing, yoga, art programs, beauty programs and nutrition courses. These kinds of classes and “life celebrations” improve quality of life, but are often out of reach for many low-income people.

That’s why Farrow called Amida Care a model for the rest of the country. People impacted by HIV don’t just need testing and pills. They need doctors who understand their needs. They need the stability of having a place to live and networks of support when times get tough. They need healthy relationships and time to pursue their interests and passions. Studies show these are all factors in keeping people on stable drug regimens, but they also simply make life worth living.

For the next six months, Democratic candidates and other supporters of the ACA – as well as proponents of a single-payer, universal health-care system – will be defending their positions on the national stage against those who would cut holes in a crucial safety net for public health. They would do well to remember the 1.2 million people in the United States who are living with HIV.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.