The U.S. has been using a dysfunctional app to “manage” a humanitarian crisis, and the situation is reaching a breaking point.

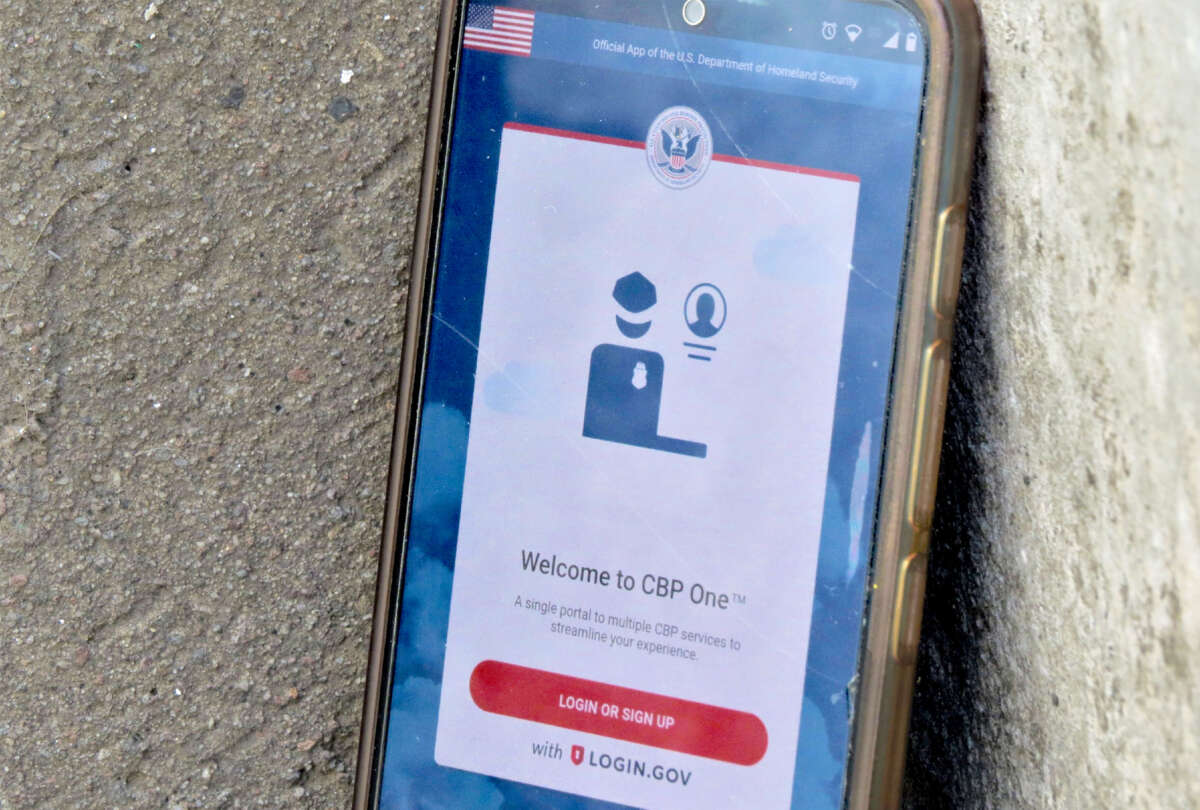

Migrants have been using the CBP One app to get appointments with border officials since January. When Title 42 expired in May, the U.S. returned to Title 8 to punish anyone who tries to cross between checkpoints and doesn’t use the app with a five-year ban.

The Department of Homeland Security calls the app “a safe, orderly, and humane tool for border management,” and says the process is “more efficient and streamlined” for migrants. But by forcing migrants to wait in Mexico for months for their appointments, the U.S. has effectively offloaded its responsibilities onto Mexico, and increased migrant vulnerability, leading to a surge in extortions and kidnappings.

The app assigns border appointments based on a combination of how long someone has been waiting and a lottery system. But migrants can’t use it until they are in central or northern Mexico. Having to wait for the app to assign an appointment violates people’s right to request asylum straight away. It is also leading to more people camping in the streets, a situation compounded by increased migrant numbers. Mexican officials detected 1,566,000 migrants without documents in just the first 10 months of 2023, compared to 445,000 in all of 2022. Last year was the highest ever registered, and this year is looking to be four times that.

“We think the flow of migrants will continue to be high,” Sergio Luna, director of the Sacred Family shelter in Tlaxcala state, and one of the coordinators of REDODEM, told Truthout. REDODEM is a network of 24 migrant shelters across 13 Mexican states.

Lupe Alberto Flores has helped migrants with the app near the border in Matamoros and at the Mexico City migrant shelter Casa Tochan. He’s also investigating the use of technology in asylum governance for his Ph.D. He says because the app is partly a lottery, people will often see that someone else only waited for two weeks and wonder if they completed their application wrong.

“The app externalizes the border … Mexico City has become the U.S.’s border,” Flores said.

The Lottery App to Process Traumatized, Fleeing People

The app “messes with your mind and causes despair. It’s hard to understand, it’s not clear what information they want,” said Michell Martínez Crespo, a lawyer who also volunteers at Casa Tochan.

He said questions about residency, for example, are unclear (migrants from further south don’t know if they should put Mexico, where they are staying while they wait for their appointment, or their country of origin), and that “creates stress, on top of how long it takes, and sometimes there are technical errors.” Because information can’t be edited, people often register multiple times, then are unsure how that will affect their waiting time.

The app also requires that people enter the address of a family member or contact in the U.S. whom they can stay with, but many migrants and refugees don’t have anyone.

Traffickers, criminals and scammers are using this technical confusion to take advantage of migrants desperate for help and information. Their fees differ a lot, but one study by refugee support group, HIAS, found migrants were being robbed of up to $20,000 by scammers promising to make their appointments for them.

Migrants have told Luna that they have paid 50 to 200 pesos in cyber cafes just for a pre-registration that wasn’t valid. “Then they arrive believing they have already registered for an appointment,” he said, explaining that migration officials often deport them when this happens.

U.S. Outsourcing Migrant Processing and Care to Volunteers in Mexico

Migrants are enchanted by the legality of the app, but want a human to hear their story, Flores argued. With the app, “there’s no person there to guide them, it is automated … so what we (volunteers) have been doing in Casa Tochan and in [the shelter in] Matamoros is bureaucratic state labor to make up for the fact that the U.S. hasn’t been doing that work,” he said.

“For the [U.S.] government, it is worth it because they aren’t dealing with people on the ground in Mexico … but humanitarian workers at the border are at boiling point because there’s no resources, there’s no space,” he added.

The U.S.’s offloading is digital, administrative and logistical. People who are rejected in the U.S. are often sent to Mexico. And, as of October, Mexico has increasingly been deporting Cubans, Guatemalans, Hondurans and Salvadorans, likely as a result of pressure from the U.S., as the increase followed a high-level bilateral meeting. Mexico detained 240,000 migrants in the first six months of this year.

Most migrants are waiting three to five months for the first notice of an appointment, then another two weeks for the assigned date. “That means people aren’t leaving the shelter for three months … and that’s partly why there’s so many people in the street,” Gabriela Hernandez, director of the Casa Tochan shelter, told Truthout.

While Casa Tochan has capacity for 46 people, it is currently housing 120. “The hardest issue is space. The whole roof (an open, fenced space on top of the offices) has become a dormitory at night. We used to have silk screen workshops and machines, but now we can’t, because all the sleeping mats are in that space. People are sleeping on the dining room table and between the beams. We only have four toilets for everyone,” she said.

In this video of the Casa del Migrante (Migrante House) shelter in San Luis Potosi, people can be seen sleeping on cardboard on floors and in the basketball court. CAFEMIN, a shelter in Mexico City that can house up to 100 people, is sheltering 650 people, with many more people camping outside.

“There are a large number of migrants traveling through the country, seeking support and to meet their basic needs, but the Mexican government isn’t responding to this emergency,” said Luna. “So there are more and more migrants living in the street, in conditions of, frankly, extreme poverty and vulnerability,” he said.

There are encampments by bus terminals, plazas, churches and migration offices. Janaiker Guerra, from Venezuela, had been staying in a tent outside the El Sagrado church for eight days when Truthout spoke to him. “We’re the ones who don’t fit inside the church. While waiting for our appointment, we survive on the bits of food that people bring us. The [Mexican] government should give us permits to stay here while we wait, but it takes a year to get a transit or humanitarian visa. So we can’t work while we wait. But they are making us wait here.”

David José Chirino has been staying outside the same church for a month. He and his wife said they have faced extortion, robbery and kidnapping on their way to Mexico. “We feel a little safer here, but there’s not a lot of light at night or food, nowhere to go to the toilet. All this, and we might get deported when we go north,” Chirino said.

In Matamoras, 2,000 people are waiting in an open-air encampment along the Rio Grande river, with no access to toilets or water, and exposed to heat, hail, flooding and to being preyed upon. Shelters by Mexico’s southern border are also overcrowded with people sleeping on the street as they wait months for transit visas in order to have documentation to travel through the country. A new caravan of 5,000 migrants left Tapachula, Chiapas, for the U.S. border in early November. One participant said he was out of money and couldn’t keep waiting on an appointment that might never come.

In mid-November, Mexican migration officials removed migrants from large camps outside two bus terminals, destroying tents and taking their belongings, then transporting migrants to southern states, where the app doesn’t work. They’ll have to repeat their journey, often on foot, back to Mexico City.

Nurturing Cartels Instead of Migrants

The U.S. and Mexico’s treatment of migrants is supporting an increase in organized crime, according to the migrant network REDODEM. The organization says because the countries are criminalizing migrants and subjecting them to security measures and deportations, cartels can easily take advantage of migrants’ desperation and lack of rights, visas and housing.

Along with the digital coyote boom, in-person attacks are also increasing. “Organized crime groups … are increasing their fees for trafficking, but are also more and more visible at different points around the country and the amount of trafficking is also increasing … traffickers go to areas where there are concentrations of migrants, including shelters,” explained Luna.

In October, Human Rights First released a report detailing how the U.S.’s “asylum ban” is causing an increase in kidnapping, torture and assaults on people stranded as they wait. It estimates a 50 percent increase in violence against migrants over the past six months. Criminal groups often kidnap migrants in order to demand ransom from their families, then torture them if they don’t receive payment quickly. They also punish migrants who try to avoid paying for their trafficking services with violence or kidnapping, or even rape and extortion.

Some people with appointments have missed them because they were kidnapped on the way, and 22 northern border organizations in Mexico denounced in July that public authorities, organized crime and bus companies are colluding to kidnap and extort migrants.

In northern Mexico, “some shelters have had to close, because basically, the organized crime groups have tried to force them to form part of a trafficking program,” Luna said. According to Human Rights First, humanitarian workers in Tamaulipas, Reynosa and Matamoros have had to stop assisting migrants after being threatened by cartels.

Migrants are fleeing unemployment, poverty, violence and the impacts of climate change. The U.S.’s policies of intervention and exploitation of the region have contributed to many of these issues and bestow a genuine responsibility onto the U.S. But “punishing people for trying to cross the border means … removing themselves from any responsibility to protect people,” Luna said.

Flores sees a clear solution: “If the [U.S.] government would invest $2 billion in humanitarian infrastructure versus all the money they spend on security, perhaps we wouldn’t see so much violence and extortion.”

Our most important fundraising appeal of the year

December is the most critical time of year for Truthout, because our nonprofit news is funded almost entirely by individual donations from readers like you. So before you navigate away, we ask that you take just a second to support Truthout with a tax-deductible donation.

This year is a little different. We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. 2025 was a year of frightening censorship, news industry corporate consolidation, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We’ve set an ambitious target for our year-end campaign — a goal of $250,000 to keep up our fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout before December 31. If you have the means, please dig deep.