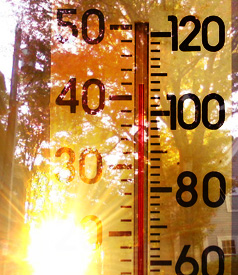

Record-breaking—and dangerous—heat waves have lately become a staple of summer. In Moscow last July and August during a tragedy that grabbed global attention, average mortality doubled, to 700 people a day. In Kuwait the temperature soared to 122 degrees. Temperatures in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia all hit 100 degrees Fahrenheit and set new daily highs as the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association declared January to August the warmest such period on record.

In China, intense heat actually caused a plague of locusts.

But while such events grab the headlines, even normal heat waves—the ones that make us run for air-conditioned homes and movie theaters—are dangerous. In fact, say two Yale University scientists, all heat waves pose public health risks more dangerous than most anyone has realized.

In a report released this week in Environmental Health Perspectives, authors Michelle Bell and G. Brooke Anderson examined U.S. heat mortality data from different kinds of heat waves. They found that during all heat waves in 43 U.S. cities from 1987 to 2005, the average daily risk of death increased by an average 3.74 percent.

Further, they found that for each 1 degree Fahrenheit rise in mean temperature and for each day a heat wave persisted, there was a 2.5 percent increased risk of death.

“We think this is an issue that’s really important for the present day in terms of thinking about the public health burden of the heat waves,” Bell told SolveClimate News. “But also under a changing climate, this could be a public health problem that is exacerbated.”

What’s a Heat Wave?

Bell, an associate professor of environmental health in the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies (co-author Anderson is a postdoctoral fellow in the Environmental Engineering Program), said that the study defined a “heat wave” as two or more days with a mean temperature exceeding the 95th percentile for a city’s average May-to-September temperatures.

Deaths were considered “heat-related” if they were not accident-related, or suicides. Cardiovascular versus cardio mortality data were also reviewed. An important conclusion, Bell said, was that not all heat waves are alike.

“We looked at what are the characteristics of a heat wave that might modify its mortality risk,” she said. “[These were] the intensity, how hot was the heat wave, its duration, and its timing in summer.”

One interesting finding was that Southern heat waves weren’t nearly as devastating as those in the Northeast and Midwest.

“In locations where it’s more typically hot, such as in the South, we think that people may have acclimated to these conditions,” Bell said. Acclimation might mean biological adaption or behavioral and physical habits like using air conditioning or drinking more water.

Acclimation, she said, also might explain why heat waves in the early part of summer bring higher mortality: 5.04 percent vs. 2.65 percent at other times.

Catastrophic Heat Waves Still a Puzzle

The researchers also separately looked at catastrophic heat waves like the ones that struck Chicago and Milwaukee in the summer of 1995. More than 500 Chicagoans died from heat-related causes over seven days (134 percent higher than the average heat wave mortality increase), as did 197 Milwaukee residents (93 percent higher) over 11 days.

The researchers wanted to see whether three heat wave characteristics—timing, duration and intensity—explained why those two 1995 events were so harmful. The answer, said Bell, is that the characteristics helped explain the harm, but not completely.

“There are clearly other things going on as well,” she said. “It could be some type of social network factors in terms of who has access to a safe place to be during a heat wave; it could be different types of interventions; our study was not able to determine what those factors are.”

Yet future studies might. Bell said she and Anderson will be taking climate change projections into account more and more. “We think there are implications for policy makers trying to design and implement programs to address heat-related, public health burdens in their communities,” she said.

“As an example, our findings indicate that communities respond to heat waves very differently; that means a program that was very effective in one community might not be the best program to avoid heat wave mortality in another community. We also found heat waves have very different responses and that characteristics of a heat wave matter.

“So if you have a program that’s very effective or not very effective for a particular heat wave, that doesn’t mean it’s going to work or not work for other heat waves.”

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.