Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

In Washington, D.C. a new model for school nurses is not only placing a strain on these medical professionals, but puts the health of numerous students in jeopardy, critics say.

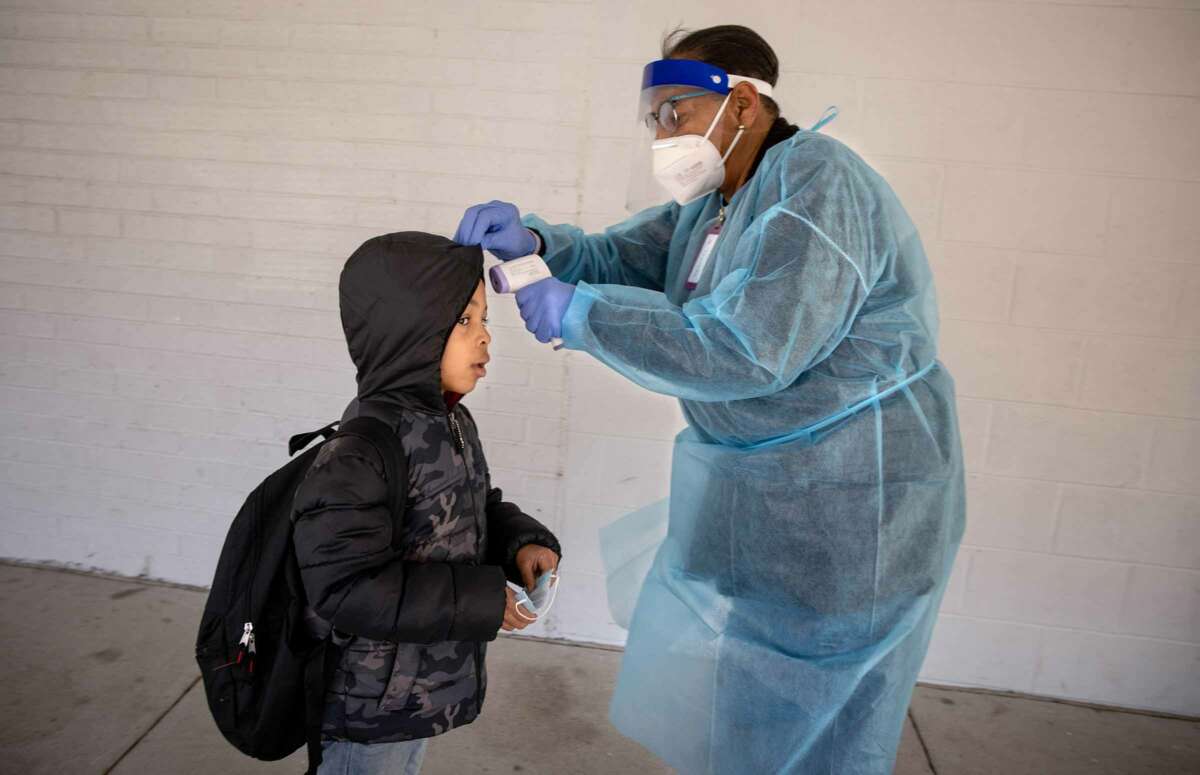

Implemented by all of D.C.’s 112 public schools and 87 charter schools this 2023-2024 school year, the new program is designed to spread out school nurses as the district copes with the nationwide nurse shortage.

Now, instead of having one registered nurse (RN) or one licensed practical nurse (LPN) per school, these licensed professionals are required to rotate between a “cluster” of four schools, meaning each school would not have a full-time nurse present for a majority of the week. These clusters of schools could consist of either public or public charter schools that are “geographically close to one another,” or no more than 10 minutes apart by car. Furthermore, each cluster would have at least five total health care workers — an RN or LPN, health technicians, and a nurse manager overseeing the program’s efficiency within their respective cluster.

According to D.C. Councilmember Christina Henderson, the program was designed to “deliver quality care to our young people and provide a level of consistency that our schools have been asking for.”

This is far from reality, though, according to Deborah Thomas, a registered nurse of over 45 years, and retired school nurse now working with the District of Columbia Nurses Association (DCNA), a union overseeing D.C. nurses. “[School nurses] are in a lot of distress,” Thomas told Truthout. “It’s understaffing. And they are starting this program right at the beginning of the school year, where there’s already a lot that has to be done.”

Overworking nurses was a possibility that the D.C. Department of Health (DOH) understood well before fully implementing the model. In fact, an example cluster created by the department outlined a grouping of four D.C. schools consisting of almost 1,750 children — meaning RNs and LPNs alone would be required to manage 875 children each. The D.C. Children’s School Services (CSS) — an entity run by the DOH that recruits practicing nurses for schools — stated that it had coordinated community outreach to families, school leaders and the DCNA before developing the program. However, numerous families admitted that they weren’t informed about the switch, while Thomas clarified that any “outreach” and negotiations to DCNA were quick and not properly carried out.

“Children’s School Services quickly tried to negotiate with us for about a month but put [the cluster model] into place immediately,” Thomas said. “We asked if they could at least do a pilot to get feedback from nurses, students and families before making changes. Instead, at the beginning of the school year, they simply put the program in progress without making sure that it was going to be a model that would help the children in the district.”

Had the CSS and DOH thoroughly assessed this program, Thomas says, they would have realized that it contradicts the 2017 Public School Health Services Amendment Act, which requires that one RN or one LPN be in each elementary and secondary public school a minimum of 40 hours per week. “The DOH and CSS and the D.C. Council are circumventing their own orders by implementing this model,” Thomas told Truthout. “What they are doing now is deciding that professional nurses aren’t needed at the [school] level and changing that.”

According to Thomas, schools have resorted to hiring full-time “student health technicians” — who require nursing assistant, EMT, or first aid certifications but are not licensed nurses.

“These health technicians are not licensed individuals [and thus aren’t] suited to work in these environments alone — but they can be paid less,” Thomas added. In fact, while the average D.C. school nurse has a $61,000 annual salary, health technicians are relatively paid $40,000 a year in D.C. This would explain why D.C. went from having at least one registered nurse working full-time in at least 102 schools last year to having only 96 full-time nurses but 88 health technicians across all 184 schools.

Now, on top of being responsible for hundreds of children across four schools, RNs must also be responsible for multiple health technicians, putting RNs’ and LPNs’ licenses in jeopardy, according to Thomas. In fact, the DCNA stresses that because health technicians lack proper training and qualifications, RNs are now expected to review and monitor their work: “Our professional licenses are put at risk due to potential errors or negligence on their part,” the DCNA clarified.

Beyond threatening RNs’ professional integrity, the replacement of on-site full-time nurses with health technicians further jeopardizes student health, as medical regulations place limitations on what these technicians are allowed to do on their own. While registered nurses have a lot of discretion — including the crucial function of administering injectable medications, conducting medical procedures and acute illness assessments — any delegation of such tasks to unlicensed professionals like health technicians must be supervised by RNs or LPNs on site. This places students with chronic illnesses — like allergies, asthma and diabetes — in tremendous danger.

“Health technicians don’t have the skills to assess the level of acuity or where this child is to make proper assessments,” Thomas told Truthout. “Their practice — especially in dealing with children with chronic illnesses — has to be supervised by a registered nurse. If that nurse isn’t on-site, the health technicians need to call them through telehealth. Then the nurse can say, ‘Ok, do whatever, give the medicine.’ If the nurse doesn’t answer, then call 911. Now, this is one of the situations where the nurses are … frankly afraid.”

Because health technicians must be supervised before administering care in medical emergencies, the response times are greater than they should be in emergency scenarios. According to Thomas, the DCNA has already received incident reports where asthmatic children have not been dealt with appropriately while waiting for health technicians to connect with RNs who were offsite. “We’re talking about children with chronic illnesses that need care,” Thomas said. “A child having an asthma attack or an allergic reaction, not getting the right care — including a proper acute assessment and sent to an ER quickly — that child could die.”

For low-income areas with predominantly Black and Brown residents, like Wards 7 and 8 — which both have the highest levels of chronic disease in the District — school nurses have played a crucial role in their communities. While the cluster model prioritizes the placement of RNs in schools with a prominent special needs and chronic illness population, that means that many nurses have been pulled away from families and routines they’ve spent years curating while working with their ill children. Myra Hines is one such nurse who worked at the same school in Ward 7 for 20 years, eventually watching over her former students’ own children, only to be taken away from that school due to the cluster model. “It really affected me health wise,” Hines told DCist. “It’s too stressful for me to continue.”

And it’s just as stressful for the parents, according to Deborah Thomas. “You have these nurses who’ve spent years collaborating with parents to take the best care of their children. All of a sudden, these parents come to find out that this nurse has shifted schools and is no longer a full-time employee working with their child.”

Thomas still holds on to hope that soon the cluster model will be eradicated, telling Truthout that the DCNA will host an open forum in November incorporating nurses, medical experts, the D.C. City Council and families of impacted children. The goal is to get the city council, the DOH and the CSS to recognize the danger this program poses for vulnerable children, and to compel them to collaborate with nurses and families for an effective solution that still grants students high standards of care even amid a nursing shortage.

For Thomas, upgrading the treatment and salaries for school nurses — which is well within the city’s now $2.2 billion school budget — could be a good start. “School nurses make $10,000 to $15,000 less than nurses, for instance, working in acute hospital nursing,” Thomas said. Meanwhile, the average nurse in D.C. can make up to $150,000 a year compared to school nurses, who make less than half that at $61,112 a year. In a petition collecting close to 700 signatures, the DCNA further stresses the need for the city to invest in qualified nursing staff rather than choosing a cursory solution that “places financial considerations” above children’s welfare. “CSS and DOH prioritize profits over student health by implementing downsizing measures that compromise quality healthcare services in schools,” the DCNA states.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.