Part of the Series

The Public Intellectual

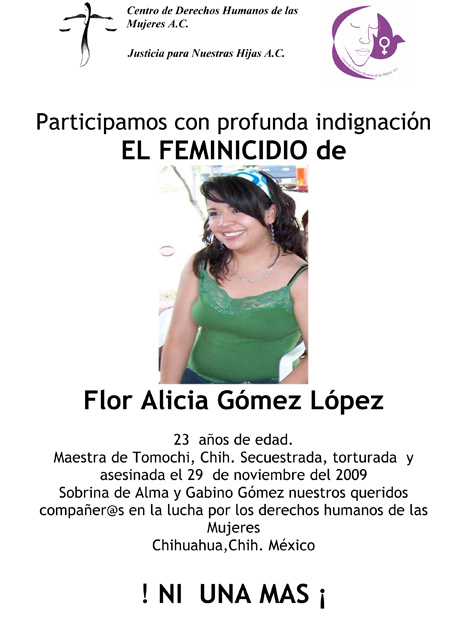

At the end of 2009, we were reviewing the page proofs for “Terrorizing Women: Feminicide* in the Américas”[1] when the Centro de Derechos Humanos de las Mujeres (Center for Women’s Human Rights) sent out an email blast announcing the latest feminicide victim in Chihuahua: Flor Alicia Gómez [Figure 1]. A rural teacher in the town of Tomochi, Chihuahua, Flor Alicia was accompanying a group of friends to a meeting when they were assaulted and beaten by an armed commando. Flor Alicia’s body was found the next day. She had been abducted, tortured and killed by a gunshot to the head.

Since the completion of our edited book, violence against women who defend human rights is growing at an alarming rate. Flor Alicia’s is one of many cases of relatives threatened or murdered for the human rights activities of their family members. Several of Flor Alicia’s relatives, including her mother, are well-known human rights defenders in Chihuahua. Her aunt is Alma Gómez, a long-time women’s rights advocate, former state senator and co-founder of Centro de Derechos Humanos de las Mujeres and Justicia Para Nuestras Hijas (Justice for Our Daughters) in Chihuahua.[2] Alma Gómez co-authored one of the chapters for “Terrorizing Women.”

The violence in Mexico is benumbing. Mexico’s so-called “Drug War” against organized criminal networks has resulted in nearly 50,000 people killed, the majority innocent civilians. Funded by the United States’ $1.4 billion Merida Initiative, the urban deployment of soldiers and federal police to fight organized crime has led to even greater insecurity throughout the country.

In the violence-torn border state of Chihuahua alone, dozens of teachers like Flor Alicia, as well as medical doctors, social service providers, journalists and human rights activists have either been assassinated or threatened. Hundreds more have fled the area. Since Mexican President Felipe Calderon launched Operation Chihuahua in 2008, deploying thousands of soldiers and military police to the region, violence and criminality have reached pandemic proportions, together with a disturbing trend of human rights violations committed by the very same security forces sent to restore order.

“Mexican armed forces,” as journalist Jeremy Kuzmarov notes, “are notoriously corrupt and have an abhorrent human rights record.” The involvement of Mexican soldiers in widespread torture, disappearance, extrajudicial murders and kidnappings is a stark reminder of the execrable legacy of state terror known as the “Dirty War,” dating to the 1960s. Under the guise of a “national security doctrine,” Mexico’s previous Dirty War involved the violent quelling of labor unionists and indigenous, land rights and student activists. In the current context, the human rights community is increasingly alarmed because the so-called “War on Drugs” is serving as the government’s smokescreen for a “new Dirty War,” aimed once again at criminalizing social activism and civil dissent. Similar to the previous era of state-sanctioned violence, the new Dirty War is being waged against the poor and urban youth, as well as against members the human rights community: labor rights and indigenous rights activists, associations of debtors and displaced people, environmental and anti-violence groups.[3]

Women defenders of human rights are especially vulnerable. A recent United Nations (UN) report on the “Situation of Human Rights Defenders” reiterated a longstanding concern about the “saliency of gender-based violence and other risks faced by women defenders of human rights.”[4] Women advocating on behalf of gender-related issues, sexual and reproductive rights, the rights of women workers and indigenous women, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intergender (LGBTI) defenders in the region are often sexually harassed and abused, raped, threatened and murdered.[5] This new Dirty War in Mexico has led to the marked rise of death threats, physical attacks, murders and attempted murders of women who speak out against violence or demand an end to pervasive impunity for human rights violations. In this respect, the ongoing murders of women human rights activists expose the persistence of gender violence against women as a tool of terror in Mexico.

Despite the rise in incidents of violence against women in countries like Mexico and Guatemala, policy debates and media coverage continue to characterize the abductions, murders, disappearances and threats against women as “narco-violence” or as “collateral damage” of the Drug Wars. This foza común (common grave) perspective on gendered violence diminishes crimes against women as much as it distorts the specificity of gender-based violence by folding it into generic categories of “criminal violence” and/or “social violence.” The siloing of gendered violence is a longstanding concern for women’s human rights activists and researchers.

In a series of talks following the publication of the book I co-edited with Cynthia Bejerano (“Terrorizing Women”), I spoke about how these cases are not random crimes or acts of violence. In these talks, I reflected on what I consider to be the book’s contributions to the study of gender-based violence against women. Our book project is part of the two-decades-long endeavor on the part of women’s human rights advocates in Latin America to disinter violence against women from the foza común mentality by naming violence specific to gender by another name: feminicidio or feminicide. The assassination, abductions and threats against women human rights defenders are part of a widespread and ongoing phenomenon of feminicide.

Research on feminicide makes an original contribution to the field of violence studies in large measure because of the distinction we draw between feminicide as a phenomenon, an analytics and a legal framework. The essays collected in the edited book provide a foundation for thinking about these three dimensions of feminicide. In the following pages, I extend a conversation we began with the book project. I reflect upon the utility of the category, feminicide, evaluating the work that it does for women’s human rights scholarship and legal advocacy. These reflections are indebted to lively exchanges with audience members from women’s rights organizations, universities, community centers and human rights forums who asked many provocative questions that immensely deepened my own thinking about these issues.

Defining Feminicide as a Phenomenon and an Analytics

The border city of Ciudad Juárez’s infamy as the capital of feminicide is by now common knowledge. The term “feminicidio” was first used in the late 1990s to describe a phenomenon of unsolved murders and disappearances in Ciudad Juárez, dating to 1993, the year women’s rights groups first noticed an unusual increase in murders and disappearances of women and girls. It was this alarming rate of violence against women in the border region and the near-absolute impunity for gender crimes that catalyzed transnational activism: the hemispheric “Por la Vida de las Mujeres” (For the Life of Women) initiative launched by the Latin American and Caribbean Committee for the Defense of Women’s Rights (known by its Spanish acronym, CLADEM); research on the subject matter; and, eventually, the elaboration of “feminicide.” One of the major epistemological contributions of the category “feminicide” in both scholarly and activist practices is its alteration of the historic system of classification that privatizes and renders invisible gendered forms of violence against women. Besides describing the phenomenon of widespread gender-based violence, the category of feminicide also provides a new analytics for violence studies.

During my public talks about feminicide in the Américas, a frequently asked question is: “Why all the focus on the murder of women, since most of the murder victims are men?” To be sure, the murder rate of men is ten times greater than the rate for women. Even in Ciudad Juárez, during the period when the city achieved its notoriety as the world’s capital of gender crimes (1993-2006), women counted for roughly 15-20 percent of the total homicides, depending on who was doing the counting. However, as I often respond, unlike male bodies, most of the bodies of murdered women exhibit high levels of sexual violence. The murders and disappearances of women occur within the context of a patriarchal society with high levels of sexism, discrimination and misogyny. Mexico, for example, has one of the highest rates of gender violence in the world, with 38 percent of Mexican women affected by physical, sexual or psychological abuse, compared with 33 percent of women worldwide.[6] Two-thirds of female homicides occur in the home, and 67 percent of women in Mexico suffer domestic violence. For Guatemala, the figure is 47 percent.

A primary impetus behind the project of “Terrorizing Women” is to unmask the forces, institutions and social actors behind this paradoxical silencing and heightening of gender violence, and most pertinent, to counter the war over numbers. One illustration of this war over numbers is found in the Mexican government’s manipulation of statistics, as told by Teresa Incháustegui, the current president of the Feminicide Commission.

At a recent meeting of the Red de Investigadoras por la Vida y Libertad de las Mujeres (Network of Women Researchers for the Life and Liberty of Women; herein “Red de Investigadoras”) in Mexico City, Incháustegui recounted how, the year after the state of Mexico (entidad federativa) adopted the law on feminicide, the governor of the state publicly announced the positive impact of the law. According to the governor, the state of Mexico had registered a 30 percent drop in the murders of women in just one year. At first, women’s rights defenders applauded the result, until they scrutinized the breakdown of deaths. In that same year, when murders of women had dropped by 30 percent, the state registered a 30 percent increase in suicides among women! The manipulation of statistics by government officials continues to obscure any accurate count of the extant level and severity of gender violence, as well as of its distinctiveness.

*In speaking about the book, I concentrate on our most noteworthy intervention, namely, the coining of the term, “feminicide,” primarily because there are competing perspectives about which term is more accurate: “femicide” or “feminicide.” A few months after the book’s publication, a professor from New York University emailed me to express her disagreement with our use. “Feminicide means the killing of femininity,” she wrote. “The proper term for the murder of women is femicide.” From our perspective, that is precisely the problem. Too often “femicide” is used as the gendered counterpoint to “homicide,” or as a way of characterizing the “murder of women.” We wanted to go beyond the limits of that definition because we felt it did not capture the complexity of gender-based violence, nor how it is qualitatively distinct from other forms of social violence prevalent today. More so than with “femicide,” the analytics of feminicide offers an alternative perspective on gendered violence.

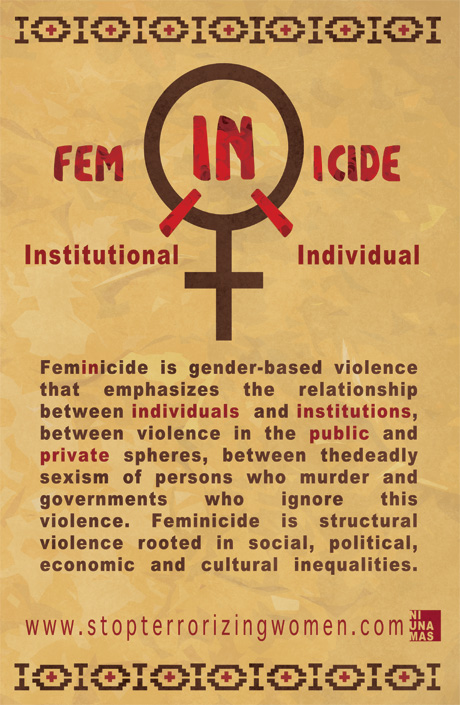

Bejarano and I decided to translate the Spanish term feminicidio literally to “feminicide” by inserting the extra syllable to the English-language term, “femicide,” partly because we felt that the extra syllable in the English term – fem-IN-icide – added a vital layer of symbolic complexity. The extra “in” functions metaphorically as a register for the relationship between violence in the private and public sphere, between individuals and institutions, between the deadly sexism of persons who murder women and governments who condone this violence, as illustrated in the poster designed by one of my undergraduate students at the University of California Santa Cruz, shortly after the publication of the book [Figure 2]. Here, the extra “IN” inextricably links INdividual and INstitutional forms of violence, symbolically representing how we conceptualize violence structurally and beyond a singular cause-and-effect model.

In the book’s introduction, we detail the rationale behind our preference of “feminicide” over “femicide.” Here, I will just highlight the most salient aspects. First of all, we note how feminicide allows a focus on gender as a social construct, insofar as many of those targeted by gendered violence are not just “biological” women, but also non-gender-conforming women in Latin America: transgender, transsexual, intersex and transvestites. Next, this new concept highlights the theoretical intervention of scholars and activists from the Global South. Since innovations in knowledge are often accompanied by new terminology, we coined the term “feminicide” to account for the new insights developed by the book’s contributors. From our perspective, their (our) interventions are breakthroughs in the study of gender violence, and a concept like feminicide marks the innovation.

As we explain in the book, gender violence is qualitatively different from other forms of violence now endemic throughout Latin America. Criminal violence and feminicidal violence are interrelated to the extent that high levels of both violence and impunity are risk factors for feminicide. Yet, for a murder to be characterized as feminicide, there must be evidence of violence related to women’s gender, specific to discrimination, sexism and misogyny, and there needs to be a determination regarding patterns of sexual abuse, physical assault and other gender-specific signs of mutilation and torture prior to the murder. As hard as it is to name “feminicide” in popular and state discourses as a particular kind of violence, it is just as difficult to analyze it from a scholarly perspective. Criminal investigators in many Latin American countries are simply not trained to gather and interpret a crime scene from a gender viewpoint. Those of us conducting research on gender violence largely depend on case files and forensic data gathered/compiled by untrained police investigators who fail to document evidence of sexual or physical abuse that occurred prior to the murder.

I begin my talks with basic observations about the gender system as a system of domination because speaking about violence in Latin America poses unique challenges for those of us who live in the Global North.

Colonialist Violence and the Problem of “Machismo”

The category of feminicide provides a new analytics grounded in a systemic understanding of violence as a gender system of domination bolstered by socially constructed gender norms of male supremacy and female submission. These gender norms are not “natural” or essential, but, rather, sustained by an assemblage of patriarchal institutions and misogynist practices embedded in law, the family, religion, education, media, the criminal justice system and corporate culture. The focus, in our case, may be on violence against women, however, a systemic understanding of violence does not render obsolete male victims, since they, too, are subjected to gendered forms of domination.

Often, when I am asked about the cause for the pandemic of gender violence in Latin America, the link between violence and masculinity in Latin culture comes up in questions like: “Is it because men feel threatened by women’s growing independence?” and, “Don’t you think that the machismo of Latino men is behind all the murders of women?” The challenge many of us face whenever we investigate or write about violence in Latin America is how to avoid reproducing the stereotype of human rights violations as cultural pathologies. This is both a challenge and a burden given the longstanding colonialist stereotype about the biological predisposition of Latinos to violence.[7]

The biological determinism behind the notion of gender violence as inherent to “Latin culture” fuels the notion of Latin America specifically (and other countries of the Global South, more generally) as the “face of human rights violations rather than the voice of criticism.”[8] Other scholars underscore the “‘cultural arrogance’ in those human rights discourses that characterize violations as discrimination (US/here) and persecution (other/there).”[9] Challenging this cultural assumption is complicated by the enormous historic weight of symbolic and discursive structures that are largely instrumental in entrenching the cultural stereotype of violence as genetically ingrained in some monolithic Latin culture. Chief among these is the linguistic symbolism of the Spanish term “machismo” (pronounced “makismo” in some English-language circles) as the most favored English synonym for exaggerated or hypermasculinity.

This colonialist stereotype about violence as inherent to traditions of the Global South – also known by the “death by culture” metaphor – uses culture in order “to explain the different forms and shapes violence against women takes,” as feminist scholar Uma Narayan explains.[10] The “death by culture” metaphor promotes the idea that the subordination of women happens in “other” cultures, or that it is intrinsic to societies of the Global South. Even the Mexican government has invoked the “death by culture” metaphor. During Amnesty International’s visit to Ciudad Juarez in 2003, one Mexican government official told Amnesty International (AI) representatives that violence against women would be difficult to stop because “machismo” is an “essential element of Mexican culture.”

I am not trying to deny the reality of violence in the region. For the past three years, Ciudad Juárez continues to be one of the five most violent cities on earth (followed by two other Latin American cities in the top ten category: San Pedro Sula, Honduras, and San Salvador, El Salvador), registering 130 murders per 100,000 residents in 2008; in 2009, the rate jumped to 191 per 100,000. [11] However, the cultural explanation presupposes a static, reified and homogeneous view of culture, one that ignores the vast diversity of the Americas. There is not one colossal “Latin culture,” but many dynamic, fluid and intersecting cultures, and just as many alternative masculinities to a one-of-a-kind “machismo.”

The cultural assumption about violence as rooted in a “machismo” inherent to Latin culture also discounts the long historic resistance to violence, along with the plethora of antiviolence activism in communities throughout the Américas. In the introduction to the book, we challenge the cultural assumptions of violence as inherent to Latino societies by highlighting the historical and structural dimensions of gender violence. Thinking about violence in these terms requires that we move beyond a linear chain of cause-and-effect models and embrace a more systemic framing for violence, emphasizing its connections, relationships and context.

Critical Human Rights Framing

The analytics of feminicide advances a more comprehensive framing for gendered violence, one based in what we call a “critical human rights framework.” First, it considers violence against women to be a violation of women’s basic human rights to “life and liberty,” as expressed in the Inter-American Convention for the Prevention, Eradication and Punishment of Violence against Women (also known as the Convention of Belém do Pará). A human rights framing for feminicide is also a way of holding governments accountable, insofar as their failure to act to end gendered violence is itself a fundamental violation of international human rights law. In this sense, gendered violence is not just perpetrated by individuals, but also by state institutions that fail to investigate and prosecute gender crimes, by individual and institutional actors such as police and military who operate with absolute impunity. The lack of government accountability and responsibility for the widespread impunity resulting from the failure to investigate and prosecute gender crimes (the failure, in other words, to exercise due diligence) has created a cesspool for further feminicidal violence.

In our critical human rights framing of feminicide, we emphasize what we call “rights for living.” Rooted in the principle of indivisibility, our notion of “rights for living” recognizes the interdependence of all human rights as central to the recognition of human dignity and life. Thinking about rights as interdependent means that violations of a woman’s civil and political rights (her rights to bodily integrity) are just as significant as the violation of her economic, social and cultural rights (her rights for living). Our critical human rights framing, based on the principle of indivisibility, thereby rejects the hierarchical ordering of rights, or the privileging of civil and political rights (so-called “first-generation rights”) over economic, social and cultural rights (“second-generation rights”). The violation of a woman’s rights to physical and personal integrity (civil and political rights) is just as egregious as a violation of her rights to social security, work, identity, health, sexual autonomy and a decent standard of living (economic, social and cultural rights). From our perspective, both categories of rights are equally fundamental for the realization of women’s subject-hood and human dignity.

The new analytics of feminicide, as we argue, points to the limits of the “personal injury” model of gendered violence. Violence against women is most often considered to be a matter of “personal injury,” or the result of physical, emotional or psychological acts by an individual or individuals, in the private sphere – a perspective that often fails to account for the structural dimensions of violence. In arguing for a systemic understanding of violence, as noted earlier – one that moves beyond a linear cause-and-effect model and connects individual and institutional dimensions – the analytics of feminicide considers an injury to a woman’s body to be an effect of multiple causes. Gendered violence is as much physical, emotional and psychological acts committed by an individual or individuals, as well as by macro systems or “impersonal” entities like a government’s economic policies that expose women to militarism and insecurity or that impede their access to employment, housing, adequate health care, education, and a sustainable and secure environment. Any social policy that limits women’s life expectancy or prevents them from realizing their full potential is considered to be a form of gendered violence. In Mexico, women’s rights advocates use the category of “feminicidal violence” for preventable deaths like those resulting from cervical cancer that goes untreated, from lack of adequate prenatal care, childbirth or suicides.

Feminicide is thus an analytic tool for thinking about violence systemically, interconnected with power relations based on gender, specific to sexism, discrimination and misogyny, across multiple sites, private as well as public, the domestic realm of intimate and interpersonal relations as well as in the public sphere of state, legislative, judicial and carceral institutions. A systemic understanding of violence considers gender violence in a network of relationships, connections and context, and in rethinking the causes of gendered violence, the new analytics of feminicide argues for a broader range of possible remedies.[12]

The Promises and Limits of a Legal Framework

Finally, I turn to the realm of law and the impact of the elaboration of feminicide as a judicial category (categoría penal). Law often serves as a “change agent,” as feminist legal scholar Nancy Chi Cantalupo once explained: “In the context of gender, law is both a tool of oppression and of liberation.”[13] As a “tool of liberation,” law can potentially alter entrenched gender norms of male superiority and female inferiority through the recognition of women as equal legal subjects of the law. The principle of international law, nulla crimen sine lege (no crime without law) is a chief impetus behind the drive for passing laws that criminalize feminicide (or femicide, depending on the country involved). Toward this aim, several contributors to “Terrorizing Women,” especially Marcela Lagarde, Hilda Morales and Ana Carcedo, have spearheaded the development of these new laws.

The recent feminicide laws in effect treat gender violence as a crime (violation) against women’s personhood, her physical and personal integrity, rather than as a violation of her “honor” or that of the family, as framed within the domestic and/or intrafamilial violence model. Specifying the crime of feminicide in this manner represents a major advance for gender justice, for these laws de-privatize or extricate violence against women from its cloister in the private sphere and, in so doing, feminicide laws are designed to harmonize national laws with international feminist jurisprudence on gender violence as a human rights violation rather than as a private family matter. This represents a major breakthrough in the realm of state-centered law, insofar as feminicide laws both redress patriarchal law’s silences and failures to treat women as legal subjects as much as they further legal advocacy in the realm of gender-based violence against women.

In 1994, the Inter American Human Rights System adopted the Convention of Belém do Pará, which led to the drafting of national laws on violence against women throughout Latin America and the Caribbean. Between 1994 and 2000, 20 countries in Latin America had adopted laws criminalizing violence against women, but within domestic legal frameworks, violence against women continued to be treated as intrafamilial or domestic violence and, in most cases, as violence against the honor of the family/woman – similar to the Geneva Convention’s framing of sexual violence in the context of war as a violation of “women’s honor.” Treating gendered violence as a crime against a woman’s (or her family’s) honor renders violence against women in moral terms, as much as it consigns it to the private sphere, in effect making it invisible.

The recent laws on feminicide/femicide in Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica and El Salvador alter the domestic legal framework by re-codifying violence against women as gender violence, as a crime against women’s personhood. The feminicide laws also frame gender violence within a “structure of gender power relations rooted in masculine supremacy as well as in the oppression, discrimination,and social exclusion of women and girls,” as Lagarde explains.[14] In this respect, introducing the crime of feminicide into the penal codes is a major development in feminist jurisprudence, marking a decided shift away from an understanding of violence against women as an issue of morality to one that treats this form of violence as a violation of women’s fundamental human rights to life and liberty.

The first feminicide law in the world, “La Ley General de Acceso de las Mujeres a Una Vida libre de Violencia” (also known as the General Law), approved by Mexico’s Congress in 2006, and the 2008 law on femicide in Guatemala are instrumental to this new conceptual framing in Latin America. Just as significant is that the shift from interfamilial violence to gender violence means that women are now the juridical subject of law, rather than its object. Besides adopting this more progressive understanding of gender violence, Mexico’s General Law calls for a guarantee of women’s right to a life free from violence; the creation of a National Data and Information Bank on cases of violence against women; a National Diagnostics on the types and modalities of gender violence; and the implementation of judicial reforms for compliance of the General Law at the federal, state and municipal levels. Unfortunately, the current situation of the General Law merely confirms Mexico’s spotty legal history: the nation has some of the most progressive laws on the books, along with one of the most regressive records of compliance with the rule of law. Four years since the promulgation of the General Law, little has changed in the area of gender justice.

In the recent gathering of “La Red de Investigadoras,” researchers and legal advocates met in Mexico City to assess the current status of the General Law at both the federal level and within the 32 states (entidades federativas). To no one’s surprise, the government’s record is dismal. To date, authorities and government institutions have failed to comply with various aspects of the law, including the design of mechanisms and judicial reforms necessary for the General Law’s implementation, as specified in the Transitory Articles (artículos transitorios). The government has so far failed to develop a National Data and Information Bank, a Diagnostics on Gender Violence Against Women and Girls, nor has it instituted emergency measures such as the Gender Violence Alert.

Since that meeting, feminist legislators and human rights defenders in Mexico have embarked on a nationwide campaign to pressure state legislatures to adopt the General Law. So far, 11 states have adopted versions of The General Law; however, at the time of this writing, only three states had even typified the crime of feminicide in their penal codes and set forth sentencing guidelines. One such state is Guerrero, where the crime of feminicide carries a sentence of 30-50 years in prison. In July 2011, the Federal District of Mexico City approved the crime of feminicide in the Penal Code of the Federal District by a majority vote of 43 in favor, 11 opposed.

There is a campaign currently underway to use the Feminicide Law to dismantle what Mexican feminist legal scholars call “leyes negras” (sic, “black laws”) or patriarchal laws that impede the exercise of women’s fundamental human rights, including the “rape law” currently in the penal code of 11 states in Mexico which allows for rape charges to be dismissed against the rapist if he agrees to marry the rape survivor. In light of a strong patriarchal family ideology that deems any female family member who has been raped to be the source of “shame” or “dishonor” for the family, there is enormous pressure on the woman to marry her assailant. Another patriarchal law of concern to women’s rights groups is a law codified in the penal code of 12 Mexican states that criminalizes abortion. Today, hundreds of women are serving prison sentences for murder, ranging from 19-29 years, as a result of terminating their pregnancies by abortion.

Law can be a “tool of oppression,” as noted earlier, especially when efforts to criminalize gendered violence are sketched within a traditional criminal justice framework. Although women human rights defenders in Mexico acknowledge the structural roots of gender violence, their policy responses, for the most part, center on a “tough on crime” approach long favored by the mainstream antiviolence community in the United States as codified in the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA): mandatory arrests and higher sentencing guidelines. As I noted in my presentation before the recent meeting of La Red de Investigadoras in Mexico City, there are several drawbacks to the adoption of a “tough on crime” approach to gender-based violence, and the traditional criminal justice framework in the United States serves as a cautionary tale.

The advantages of VAWA in terms of raising public awareness about the prevalence and severity of gendered violence in the United States are eclipsed by its shortcomings. Chief among these is the issue of the differential impact of VAWA’s legal provisions. As the composition of the prison population demonstrates, poor men, and, especially, men of color, are more likely to be arrested, charged and imprisoned for gender crimes than white, middle class or wealthy men.[15] VAWA’s “tough on crime” emphasis on mandatory arrests and higher sentencing for violent perpetrators may have other unintended but equally destructive effects on the larger social world in which we live.

Psychologist and death penalty expert Craig Haney’s extensive research on the dynamics of prison life offers sobering lessons about the limits of incarceration. In a compelling account of the devastating impact of the carceral experience, Haney argues that prison environments “are important sites for the production of two pernicious social evils that continue to plague our society: “toxic masculinity” and “persistent racism.”” The dehumanizing and degrading conditions of prison life foster pathological prison cultures that “destructively transform and psychologically disfigure the persons who are kept inside of them.” As Haney explains, prison culture turns “frightened young men” who enter the carceral system into “vitriolic racists” and “raging misogynists.”[16] The psychological harms inflicted on inmates by a prison culture of violent masculinity, as Haney’s astute observations suggest, significantly diminishes the likelihood of rehabilitating inmates convicted of gender-based violence. Against this backdrop, locking up violent offenders is the least optimal solution for ending feminicidal violence.[17]

Alternatives to the traditional criminal justice emphasis on punishment are necessary if we aim to transform the context in which feminicidal violence thrives: poverty-stricken communities beset by high unemployment, low levels of education, lack of a social infrastructure and public services, a militarized response to crime, and the gender norms of male domination and female submission. Remedies for gender crimes are determined by how one defines the causes.

In Latin America, Cuba has developed an alternative “soft on crime” policy response to gender-based violence, as detailed in a persuasive co-authored study by legal scholar Deborah Weissman (also a contributor to “Terrorizing Women”) and Marsha Weissman. The Cuban response to domestic violence and criminal delinquency, as Weissman and Weismann explain, is a case example for how remedies for gender violence are determined by the definition of its causes. Cuba’s critical criminologists attribute violent behaviors to structural conditions like low levels of education, unemployment, social stresses and entrenched gender norms. In this context, social policy responses for remedying and responding to gender violence and juvenile delinquency in Cuba privilege education and prevention; individual punishment and incarceration are considered as “the last resort.”[18] By emphasizing causal factors like “socio economic deprivation and culturally determined gender roles,” the Cuban model advances alternatives to punitive justice in the design of broader social policy responses to gender violence.

Women’s human rights defenders in many countries of Latin America are rightfully exasperated. Viewed from the prism of Mexico and Central America’s escalating violence, “tough on crime” legalistic sanctions against gendered violence, as elaborated in feminicide laws, seem plausible, particularly in light of the near-absolute impunity and government indifference to gender crimes. Yet, I remain ambivalent about the efficacy of the new feminicide laws, divorced from major structural changes, a major overhaul of dysfunctional state judicial systems, the purging of widespread corruption and abolition of the historic structure of impunity.

Coming to Grips

My writing and speaking about feminicide entails a reckoning with the deeply troubling and contradictory situation of women’s vulnerability and agency. While feminist research contributes to a more complex knowledge about feminicide as a phenomenon, an analytics and a legal category, egregious violations of women’s human rights continue to terrorize the social worlds where we live. In Mexico, women’s human rights groups have long held that police failed to respond to gender crimes because “they feared organized crime was involved, or because they were involved themselves, or both.”[19] Police indifference to gender crimes is rooted in a system of illegality so interpenetrated in the state structure that it blurs the distinction between state institutions and criminal networks, and between government agents and criminal agents.[20]

As further illustration of the precariousness of women’s lives in the borderlands region, I refer readers to the image on the cover of our book, “Terrorizing Women” [Figure 3]. Taken by my co-editor Cynthia Bejarano, the photograph features a protest march staged on the Mexican side of the Santa Fe International Bridge, on the site where activists placed the “Ni una más” cross memorializing the hundreds of murdered women in Ciudad Juárez. It is many of these courageous women, compelled to act by the life-altering trauma of personal loss, whose lives are now threatened by the terror of feminicidal violence. Their extraordinary struggle to end violence is being threatened by the force of greater terror.

Initially, we selected the image because it symbolizes women’s agency, the resilience of mothers who weep over horrendous loss and despite the devaluation of their lives, courageously transform themselves from victims to human rights activists. We felt that the photograph captures women’s role as political actors and their intersecting lives as human rights defenders, mothers, sisters, daughters and friends of the murdered and disappeared women.

The photograph pays homage to these mothers/activists at the forefront of “Ni una más” (“Not one more”), first launched in 2002 as a campaign, slogan and chant taken up by the global movement to end feminicide and gender violence. Ni una más are three words appearing in various forms on the cover of our book, as in the background, embossed on the large wooden cross that is fastened on a pink placard bearing 268 soldered nails, each representing a woman murdered in Ciudad Juárez between 1993-2002. Next to the cross, the slogan “Ni una más” is engraved on the poster held by a woman activist. “Ni una más” adorns the pink hats of members of the Mujeres de Negro (Women Dressed in Black) feminist group that spearheaded the anti-feminicide campaign.

Since the launch of the new Dirty War in Mexico, several women human rights activists involved in the Ni una más campaign have been assassinated, assaulted or threatened. Paula Flores, prominent women’s rights activist, recently shut down her community-based operations in Ciudad Juárez. After her daughter, Sagrario González, was abducted and murdered in 1998, Flores started the first mother-activists group, Voces sin Eco, (Voices Without Echo/Sound) an internationally recognized organization best known for launching the “cross campaign” of painting black crosses on pink backgrounds that became the symbol of the anti-feminicide campaign. A few years later, Flores established the Fundación María Sagrario in honor of her daughter. Until recently, the foundation operated a child-care center and an after-school tutoring and recreational program for children in the violence-torn community of Lomas de Poleo. After receiving numerous death and extortion threats, Flores announced the suspension of the foundation’s activities in October 2010. Flores’ close collaborator, Eva Arce, mother of Sylvia Arce, who disappeared in 1998, has also been repeatedly threatened and attacked. A celebrated poet and anti-feminicide activist, Arce’s account is featured as the first testimonial in our book.

Other anti-feminicide activists like Marisela Escobedo have been murdered. Escobedo’s brutal assassination in front of the governor’s palace in Chihuahua City was captured on a police security camera and later broadcast on YouTube in December 2010. Escobedo had led a two-year campaign to bring her daughter Rubi Freyre’s murderer to justice. On the Day of the Dead celebration, Escobedo participated with members of Justicia para Nuestras Hijas in their annual gathering before the Ni una más cross facing the State Capitol, where they gather each November to honor the feminicide victims by pinning names of their female kin to the cross and reciting the names of the year’s murdered women. That month, the mothers pinned 400 names of murdered women and girls to the cross, and on December 16, Escobedo’s name would be added to the list. In her final public statement to reporters, Escobedo declared: “I will not leave this place until they detain my daughter’s assassin,” vowing to continue her protest in front of the “Ni una más” cross facing the State Capitol. Nine days later, before dozens of witnesses, Escobedo was shot to death as she attempted to escape from the lone gunman.

Then, two weeks later, the Ni una más movement was stunned by another brazen murder of a prominent women’s rights defender. On January 6, 2011, poet Susana Chávez, author of the slogan “Ni una más,” was brutally assassinated by three men who sawed off her hand after strangling and mutilating her. A few months later, Malu García Andrade (pictured on the upper lefthand corner of the book’s cover) was forced to flee the city with her children after unidentified men set her house on fire. Co-founder of the anti-feminicide group Nuestras Hijas de Regreso a Casa, (May Our Daughters Return Home), García first became a human rights defender after her sister, Lilia Alejandra García Andrade, was abducted, raped and killed in 2001. Later, in December of 2011, García’s mother Norma Andrade (also co-founder of Nuestras Hijas) was shot in the chest and hands by several gunman, and, at the time of this writing, Andrade remains hospitalized in serious condition.

Clearly, Calderon’s militarized approach has only exacerbated feminicidal violence in Mexico. Washington’s Merida Initiative and the infusion of US counternarcotics military aid has undoubtedly exacerbated the level of gender-based violence committed by Mexican and Central American security forces, rival drug cartels and paramilitary groups. In light of escalating violence and criminality, the Mexican people and human rights communities are demanding an end to the US funding of the “War on Drugs.” Already in 2010, the United States withheld $26 million of the $1.4 billion “drug enforcement aid out of concerns over police and military abuse.”[21] It is time to go one step further and demand an end to the military approach to dealing with gender crimes and violence.

Feminicide is a phenomenon that should concern the human rights community, for unless we can put an end to the militarized solutions to social problems and dedicate our energies to tackling the structural roots of violence in general, the prospects for ending gender violence in the Americas seem dim. I remain hopeful about the possibility of ending all forms of violence throughout the Americas because coming to grips with feminicide is also about imagining a future without it; it is about rendering the phenomenon visible so that we can eliminate it; it is about advancing an analytics for a comprehensive standpoint on the root causes of gendered violence. Coming to grips with feminicide means imagining a world where human dignity and social equality involves dedicating ourselves to ending all forms of violence and creating new global futures of justice and peaceful coexistence.

Thanks to Sarah Banet-Wieser for her helpful comments.

(Image: Chris Cuadrado)

References

1. Cynthia Bejarano is the co-editor of “Terrorizing Women: Feminicide in the Américas.” Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

2. Both are community-based organizations that provide legal and social support to the families of the murdered and disappeared women.

3. Kent Paterson, “The Silencing of Women’s Voices,” Frontera Norte-Sur, March 7, 2011; “Ciudad Juárez Mourns, Organizes,” February 28, 2011. Available at https://frontera.nmsu.edu/. Kent Paterson, “Mexico’s New Dirty War,” Americas Program, 30 April 2010. See also Maureen Meyer, “Abuso y miedo en Ciudad Juárez: un análisis de violaciones de los derechos humanos cometidas por militares en México,” Centro de Derechos Humanos (PRODH) y WOLA (Washington Office on Latin America), 5 October 2010, available at:

https://www.wola.org/es/noticias/violaciones_a_los_derechos_humanos_cometidas_por_el_ejercito_mexicano_descritas_en_el_nuevo

and Randal C. Archibold, “Rights Groups Contend Mexican Military has Heavy Hand in Drug Cases,” New York Times, August 3, 2011, A10.

4. Margaret Sekaggya, “Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights defenders, Margaret Sekaggya,” Human Rights Council, Sixteenth Session, United Nations, 20 December 2010, A/HRC/16/44, p. 7.

5. Sekaggya, “Report of the Special Rapporteur,” pp. 9-12.

6. “38 percent of Mexican Women Suffer Gender Violence,” Latin American Herald Tribune, 21 July 2010: https://laht.com/article.asp?ArticleId=360771&CategoryId=14091.

7. See Rosa-Linda Fregoso. “meXicana Encounters: The Making of Social Identities on the Borderlands.” Berkeley: The University of California Press, 2003.

8. Beverly Ackerley. “Universal Human Rights in a World of Difference.” Cambridge University Press, 2008. 289,

9. Deborah Weissman, Caroline Bettinger-Lopez, Davida Finger, Meetali Jain, JoNel Newman, Sarah Paoletti, “Redefining Human Rights Lawyering Through the Lens of Critical Theory: Lessons for Pedagogy and Practice,” Legal Studies Research Paper Series, University of Miami School of Law. Research Paper No. 2011-08. Paper can be downloaded at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1768167.

10. Uma Narayan, quoted in Ratna Kapur. “Erotic Justice: Law and the New Politics of Postcolonialism.” Portland, Cavendish Publishing, 2005. 181.

11. “Ciudad Juárez, la más violenta del mundo,” El Universal/México D.F.

12. At a recent meeting of the Red de Investigadoras para la Vida y Libertad de las Mujeres, Marcela Lagarde declared: Feminicide results from “masculine superiority, as well as in the oppression, discrimination, exploitation, and above all, the social exclusion of women and girls, legitimated by the devalorization, hostility, and degradation of women. Social inequities are moreover strengthened by social indifference and impunity by the State toward crimes against women.”

13. Nancy Chi Cantalupo, “Using Law and Education to Make Human Rights Real in Women’s Lives,” IN Eds Debra Bergoffen, Paula Ruth Gilbert, Tamara Harvey, and Connie L.McNeely, eds. “Confronting Global Gender Justice.” New York: Routeledge, 200-212.

14. Lagarde’s comments before the Red de Investigadoras, op cit.

15. Two-thirds of the prison population are men of color, primarily African American and Latinos. See Correctional Populations in the United States, 2009 (NCJ 231681).

16. Craig Haney, “The Perversions of Prison: On the Origins of Hypermasculinity and Sexual Violence in Confinement,” American Criminal Law Review, 48, 121-141 (2011).

17. Inmates in Mexican prisons fare no better. See for example, Mercedes Peláez Ferrusca, “Derechos Humanos y Prisión. Notas Para el Acercamiento,” Boletin Mexicano de Derecho Comparado. Instituto de Investigación Jurídica de la UNAM. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Available at:

https://www.juridicas.unam.mx/publica/rev/boletin/cont/95/art/art8.htm#P6. Also see, “Twenty die in Mexican prison fight near US border,” The Guardian, 15 October 2011.

18. Deborah Weissman and Marsha Weissman, “The Moral Politics of Social Control: Political Culture and Ordinary Crime in Cuba,” Brooklyn Journal of International Law, 2010: 313-367, 342).

19. Kent Paterson, “The Silencing of Women’s Voices.”

20. The complicity of state authorities with drug cartels is the subject of the French documentary, “The City that Murders Women.” In it, directors Mark Fernandez and Jean Rampal document how both governors of the state of Chihuahua, Francisco Barrios (Partido Acción Nacional, PAN) and Patricio Martinez (PRI) prevented investigations linking feminicide to narcotraffickers. In the weeks before he was assassinated, attorney Sergio Dante Almaraz told reporters, “Creo que las muertes de las jovenes obedecen a una razon fundamental, es el daño collateral de la presencia del narcotrafico en Ciudad Juarez.” (“I believe that the deaths of young women obey a fundamental logic: they are the collateral damage of the presence of narcotrafficking in Ciudad Juárez.”)

21. Randal C. Archibold, “Rights Groups Contend Mexican Military Has Heavy Hand in Drug Cases,” New York Times, August 3, 2011: A10.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.