Part of the Series

Climate Disruption Dispatches

The fossil fuel industry knows it’s the world’s largest source of total greenhouse gas emissions, and that wealthy countries must take decisive action to reduce those emissions to avoid catastrophic global warming by the end of the century. The industry also knows that green tech and renewable energy is only getting cheaper. The latest climate report released this week by the United Nations (UN) makes these facts alarmingly clear.

The UN reports that emissions from the fossil fuel industry reached a record high in 2018, with no “peak” in sight. Every year of “postponed peaking” means deeper, faster cuts in emissions will be needed in the future. Change must come quickly. In response to these facts, the industry is pushing to establish infrastructure capable of sustaining oil and gas production for decades, even if developed nations turn away from fossil fuels for energy. For example, in the United States and across the world, the industry is hedging its bets on petrochemical and plastics plants fed by oil and fracked gas.

This brings us back to Cancer Alley, the petrochemical corridor along the Mississippi River in southern Louisiana where seven large new facilities have been approved since 2015, and five more are awaiting the go-ahead from the government, according to ProPublica. One of the proposed plants, a $9.4 billion plastics megaplex planned by the Taiwanese company Formosa in St. James Parish, could triple the level of toxic, cancer-causing air pollution in an area already inundated by industry.

The plant is slated to be built just down the road from Sharon Lavigne’s home, and she fears Formosa would wipe her historic, majority-Black community off the map. Along with other Cancer Alley activists, Lavigne has protested the proposal at one public hearing after the next and organized marches to the state capital of Baton Rouge. Opponents say it’s a classic case of environmental racism, but Formosa enjoys plenty of political support from local and state officials and has glided through the permitting process.

So, Lavigne took her case to Congress.

“People in St. James need help from our elected officials,” Lavigne said in her testimony to the House Committee on Energy and Commerce last week. “Our people are sick, and they are dying.”

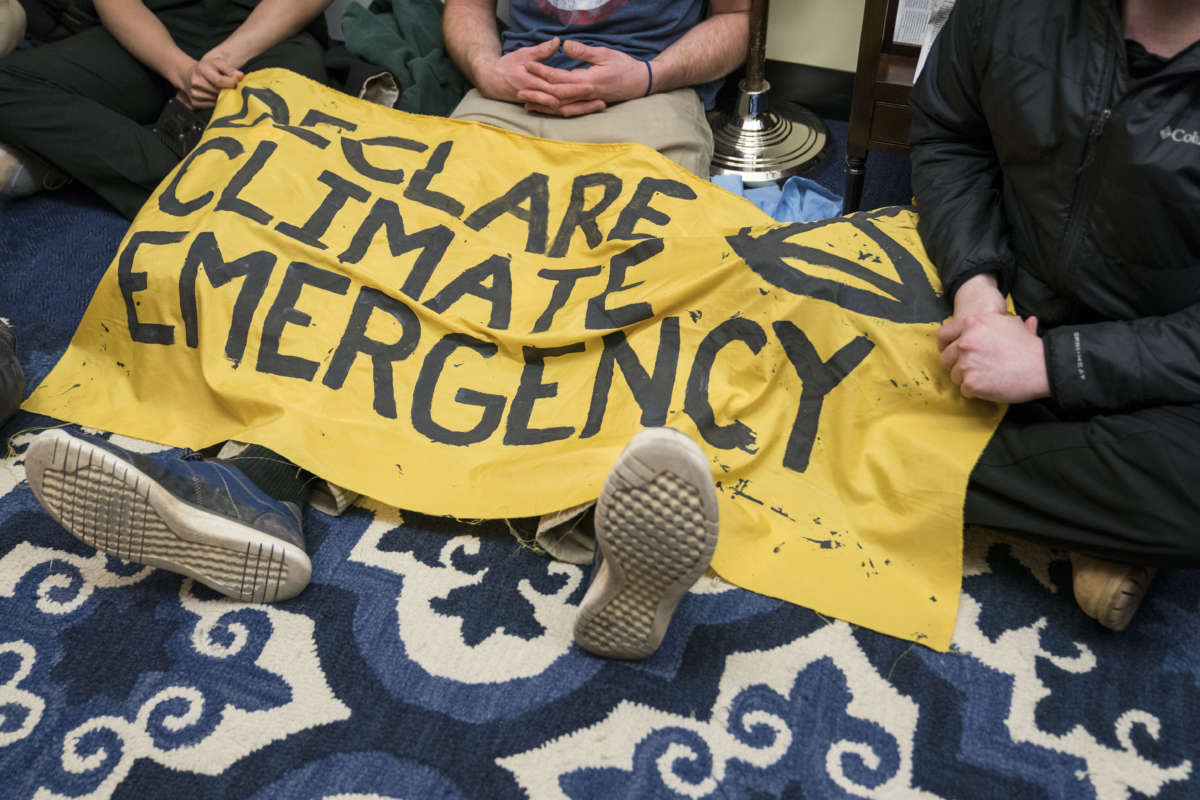

Meanwhile on Capitol Hill, hunger strikers with the climate direct action group Extinction Rebellion were camped out in the entrance of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office, demanding the Democratic leader meet with them to discuss the climate crisis. After they learned Pelosi would not be returning before Congress went on break last Thursday, they stormed inside Pelosi’s office in protest of the “lip service” Democrats are paying to the climate crisis. Nine activists were arrested.

“Every day the evidence piles up at your desk, but you have yet to pass even symbolic legislation recognizing the climate crisis as a national emergency,” Extinction Rebellion wrote in a letter to Pelosi. “With all due respect, you have failed.”

With emissions rising and progressives like Sen. Bernie Sanders and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez inspiring young voters and activists with visions for a Green New Deal, Democrats are coming under mounting pressure to push for sweeping action on climate change. Simply reducing fossil fuel consumption is not enough.

Earth

Fossil fuel production must come to an end, and the industry must be held accountable for the environmental damage and public health problems it has caused, according to a recent letter from over 260 organizations to Pelosi and Rep. Kathy Castor, the Democratic chair of the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis. The letter emphasizes that front line communities like Lavigne’s and so many others, where the fossil fuel industry’s daily impacts on poor and marginalized people are magnified by the crisis, should not only be prioritized for investment in the transition from fossil fuels; their leadership and vision should be front and center in policymaking.

Mitch Jones, director of the climate and energy program at Food and Water Watch, said Congress has a massive opportunity to combat climate change while addressing decades of economic and environmental injustice in communities from Appalachia to the Gulf South and beyond.

“Congress can direct investment into these communities for the clean energy economy; manufacturing solar panels and wind turbines,” Jones told Truthout. “They can guarantee good family supporting jobs that we are going to need in perpetuity, instead of condemning their residents to more public health problems and more environmental degradation and more dependence on an industry that we know has to go out of business in the next couple of decades.”

Thanks to decades of grassroots activism in the environmental justice movement — and now the global climate emergency — these types of ideas are finally seeping into policymaking, at least among some leading Democrats.

Along with other Democratic presidential hopefuls, Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren promise massive investments in the nation’s most environmentally vulnerable communities. Sen. Cory Booker has introduced a sweeping bill to codify federal environmental justice programs and made the issue central to his campaign. Sen. Kamala Harris introduced legislation to tackle environmental racism and give front line climate communities a leadership role in building a Green New Deal.

Most recently, 150 House Democrats signed on to a bill with the goal of transitioning the U.S. to 100 percent “clean energy” by 2050, the deadline climate scientists have given to avert the worst impacts of climate change. According to a fact sheet, the legislation focuses on job creation and improving conditions for “low-income and rural communities, communities of color, Tribal and indigenous communities, deindustrialized communities, and other communities disproportionately impacted by climate change.”

Such language may fire up the Democratic base, but passing the bill into law with President Trump in office is virtually impossible. Trump has repeatedly threatened to cancel a small federal grant program for environmental justice communities, and his rollbacks of pollution controls are a threat to human life. With a majority in the House, Democrats could send a powerful message by passing bold climate legislation ahead of the 2020 elections. However, so far, they have failed to pass any significant climate legislation.

Meanwhile, climate disruptions continue across the world and emissions continue to rise. It remains to be seen whether the government can act swiftly enough to transition away from fossil fuels — and whether vulnerable communities like St. James will be left behind.

Air

Levels of heat-trapping greenhouse gases in the world’s atmosphere have reached a new record high, continuing a long-term trend that dooms future generations to a future of rising temperatures, more frequent extreme weather, sea level rise and other disruptions, according to a bulletin released this week by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

The global average concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere increased from 405.5 parts per million to 407.8 parts per million in 2018, surpassing the average over the past decade.

“It is worth recalling that the last time the Earth experienced a comparable concentration of CO2 was 3 to 5 million years ago,” WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas said in a statement. “Back then, the temperature was 2 to 3°C warmer, sea level was 10-20 meters higher than now.”

Atmospheric concentrations of methane and nitrous oxide, two potent greenhouse gases, have also rapidly increased over the past decades. The Trump administration is currently relaxing rules requiring the oil and gas industry to limit the amount of methane that leaks from its equipment into the atmosphere.

Concentrations of greenhouse gas in the atmosphere are different from emissions into it. (Emissions are the main focus of the bleak UN report also released this week.) Emissions are gases entering the atmosphere from a smokestack, for example, while concentrations are what remain in the atmosphere after “complex interactions” with the Earth and its oceans, which absorb some emissions.

Of all the greenhouse gases, carbon dioxide accounts for about 80 percent of “radiative forcing,” the warming effect on climate caused by greenhouse gases lingering in the atmosphere. Since 1990, radiative forcing has increased globally by 43 percent since 1990. Carbon dioxide can stay in the air for centuries.

“There is no sign of a slowdown, let alone a decline, in greenhouse gases concentration in the atmosphere, despite all the commitments under the Paris Agreement on Climate Change,” Taalas said. “We need to translate the commitments into action and increase the level of ambition for the sake of the future welfare of the mankind.”

Both the WMO and the UN reports were released ahead of the UN international climate summit being held in Madrid next week.

Water

Two explorers attempting to ski 1,000 miles across the frozen Arctic Sea have been slowed by thinning ice, The Guardian reported this week.

Mike Horn of South Africa and Børge Ousland of Norway are traveling across the Arctic ice on skis and pulling sleds of supplies. They set off from Alaska in August by boat, and plan to be picked up by another boat at the other end of the ice sheet, closer to Greenland. The pair hopes to finish their trip next week, before the rations run out — but there’s cause for concern.

Thanks to climate change, the ice they are traversing is thinner than usual, making it more prone to drifting and changing its position. This has slowed the explorers’ progress, and with rations running out, their spokesman described the final effort as a “mad dash.” Rescue teams in Norway were making precautionary plans in case they must be rescued.

Scientists are increasingly worried about the cryosphere — the frozen parts of the Earth that regulate its temperature, as well as water levels elsewhere. In recent decades, global warming has led to the shrinking of ice sheets, glaciers, Arctic sea ice and snow cover. This melting contributes to warmer ocean temperatures and surface warming in colder regions, further destabilizing the cryosphere and the Earth’s weather systems.

Most recently, the WMO warned that melting glaciers and mountain ice threatened people living in regions across the world. The Earth’s glaciers, snow, permafrost and ice are the root source of drinking water for about half of the global population, but as the world warms, these freshwater supplies are becoming increasingly unpredictable. As ice and snow melts, more water rushes downhill, increasing the risk of flooding. Floods account for one third of natural disasters in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region, and climate disruption has put about 1 billion people at greater risk in that part of the world alone.

Fire

Another wildfire in California forced the evacuation of more than 2,000 homes from the mountains outside Santa Barbara this week. Firefighters were able to contain 20 percent of the fire by Wednesday morning. Thanks to their efforts and some rain showers, most evacuees have returned home, according to local reports.

The Cave Fire, as it was dubbed, burned more than 4,300 acres by Wednesday along some of the highest ridges in Santa Barbara county, lighting the night sky up with flames. Large wildfires in the western U.S. consume more than twice the area that they did 50 years ago, and the average wildfire season is 78 days longer, according to the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions.

Lightning or an untended campfire may spark a wildfire — about 80 percent are caused by people — but climate change plays a role in their spread. Warming temperatures cause earlier snowmelt and hotter, drier summers in California and across the West, contributing to larger and more frequent fires. Using data gathered by NASA satellites, scientists have confirmed an increased risk of fires and an increase in burning globally, because the Earth is hotter and dryer than it was two decades ago.

Forest fires larger than 1,000 acres occur five times more frequently in the U.S. today than in 1970, and on average, they burn ten times the area compared to fires recorded decades ago. Last month, the Kincade Fire in northern California forced hundreds of thousands of people from their homes. Recent wildfire seasons in California — and the 2017 season in particular — have been considered unprecedented in terms of intensity and damage to property.

Reaching the Tipping Point

While scientists continue to debate how the “cascading” effects of climate change may play out depending how quickly governments are able to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, it’s clear that climate disruption continues all around. With the UN climate summit approaching, scientists are warning that climate-stabilizing systems, such as the cryosphere and the carbon-absorbing Amazon rainforest, are reaching “tipping points.”

It’s also clear that the most vulnerable among us are being hit first and hardest. Consider Sharon Lavigne’s neighborhood in Cancer Alley, which is nestled behind a levee in the Mississippi River’s floodplain. The Mississippi basin saw record flooding earlier this year, forcing authorities in Louisiana to open spillways to divert water and prevent widespread flooding. Significant increases in climate-related rainfall and flooding have been documented in the Midwest, and that affects everyone downstream.

Meanwhile, the industry that dominates global greenhouse gas emissions grows around Lavigne’s home, threatening to dramatically increase the toxicity of the air she breathes. In her testimony before the House committee last week, Lavigne called for a moratorium on petrochemical development in St. James Parish that would prevent existing industry from expanding and stop Formosa in its tracks.

“We have seven districts in St. James, and they are putting all the industry in the 4th and 5th districts,” Lavigne said, referring to districts where residents tend to be low-income and Black. “So, we need something to stop the industry from coming in.”

Rep. Nanette Diaz Barragan, a Democrat from a diverse California district where communities of color face pollution from the Port of Los Angeles and the oil industry, asked Lavigne about placing moratoriums on development in hard-hit communities elsewhere. If Congress passed legislation banning fossil fuel development near already-overburdened neighborhoods, it would deal a massive blow to an industry that often builds in lower-income areas and communities of color perceived to have little political clout.

Such legislation would also be unprecedented. Democrats are currently debating a number of climate bills ranging from the Green New Deal to a carbon tax and other market tweaks favored by centrists, and only the most progressive contain environmental justice provisions. Passing any of these bills through the GOP-controlled Senate would be difficult, despite the dire warnings from scientists.

For now, the fight is on the front lines.

“Now, we’re going to fight Formosa and we intend to win,” Lavigne told lawmakers. “Right now, they’re trying to get their air permit; we’re going to stop them. They’re coming in here to finish killing us. We’re already sick.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.