After years of delays and cost increases, one of the most expensive coal-burning power plants ever built in the United States is set to be up and running in Kemper County, Mississippi, sometime next year. Outfitted with technology promoted by the Obama administration to fight climate change, the Kemper plant will capture climate-warming carbon emissions before they hit the atmosphere.

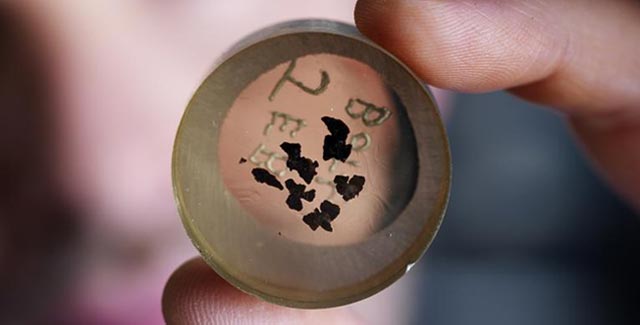

Here’s the catch: The Kemper plant plans to sell the captured carbon dioxide to Denbury Resources, an energy company that specializes in “enhanced oil recovery.” Denbury wants to pump the carbon into old wells in nearby oil fields to force remaining reserves to the surface.

Trapping carbon dioxide from burning coal and using it to extract more fossil fuels may seem like a counterintuitive approach to addressing climate change, but that’s exactly what the Obama administration hopes the industry will do. The Department of Energy (DOE) has spent years promoting enhanced oil recovery to attract industry investment in “carbon capture and sequestration” (CCS), a so-called “clean coal” technology that is supported by billions of dollars in federal aid to researchers and private companies but has yet to be proven on a large scale.

A similar coal-to-oil project broke ground in Texas last month. With help from $167 million in DOE funding, the massive Petra Nova project will upgrade a power plant near Houston with equipment to trap 1.4 million tons of carbon dioxide annually. The carbon dioxide will be processed and shipped to oil fields 80 miles away.

US power plants are responsible for 40 percent of the nation’s carbon emissions and about 6 percent of emissions globally. Some of the nation’s dirtiest plants emit as much carbon dioxide as the entire economies of small countries. Carbon capture advocates say CCS would help the top industrial polluters like the United States and China reduce their emissions without turning away from vast domestic fossil fuel reserves.

Environmental critics, however, say carbon capture is a clean-coal pipedream that would only encourage the nation’s dependence on dirty fossil fuels. For the growing climate justice movement, which brought more than 300,000 demonstrators into the streets of New York City on September 21, real solutions to climate change benefit people and the planet, not big business.

“It makes me want to remember the post-financial crisis and the 99% marches, the Occupy movement,” said Greenpeace legislative representative Kyle Ash, reflecting on the historic climate protests. “A lot of that was about corporate and government cronyism and Washington spending public tax dollars in a way that only benefits rich people. . . . CCS is a perfect example of that kind of government policy.”

A $6 Billion Experiment

While the technology is not entirely new, CCS is so expensive that the utility industry would not be able to invest in it without government incentives to grease the wheels. Congress has allocated $6 billion since 2008 toward developing CCS, according to the Congressional Research Service. More than half of the funding came from President Obama’s 2009 economic stimulus package.

The Obama administration spends huge chunks of the CCS funding on partnerships with private industry that have had mixed results. Industry partners have abandoned at least three federally funded CCS projects due to high costs and regulatory uncertainties, and last year internal auditors determined that the DOE bungled the oversight of millions of dollars in grants and reimbursements to private partners.

Earlier this year, the DOE committed to $1 billion in funding for FutureGen 2.0, a public-private effort to install a CCS system on an aging power plant in Illinois. The $1.65 billion project represents the CCS dream – a future where 90 percent of the carbon dioxide produced by a new fleet of power plants is pumped into underground wells and permanently trapped in geological formations deep beneath the earth.

That dream has had some trouble becoming a reality. The Bush administration initially proposed FutureGen in 2003 but scrapped the project years later when funding dried up. Former Energy Secretary Stephen Chu revived the project with the promise of economic stimulus funding during the early years of the Obama administration, but lack of incentives for private investors and other troubles – including a legal challenge filed by the Sierra Club – has kept FutureGen 2.0 from breaking ground. (Chu left the DOE and joined a Canadian carbon capture technology company last year.)

After more than a decade of planning, FutureGen 2.0 is still in its planning stages. The administration kept the project moving with the recent approval of a federal permit – the first of its kind in the United States – to build ultra-deep injection wells for carbon dioxide, but the American Recovery Act requires that the DOE’s $1 billion in federal aid is spent by September 2015, leaving the consortium of energy firms behind FutureGen 2.0 with less than a year to rally private investment and shake off challenges from environmentalists.

Ash said the project is an outlier. Like the Kemper plant, a majority of government-sponsored CCS projects have been linked to oil recovery, not permanent geological storage, because the energy industry is more interested in harvesting cheap carbon dioxide for oil production than curbing pollution.

“It’s clearly for political reasons that the administration keeps pushing [CCS],” Ash said.

The Kemper plant, considered by experts to be a “flagship” CCS project in the United States, has received $270 million from the DOE and millions more in tax incentives. The project has been plagued by construction delays, material shortages and other setbacks, however, and its estimated cost has more than doubled to nearly $5.6 billion since construction began in 2010.

Despite the challenges and setbacks, CCS supporters like the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) insist that the technology is ready to roll, citing power plants that regularly capture small fractions of their carbon dioxide to sell to beverage companies.

“To date, the power sector has not used CCS broadly, but not because of any technical shortcomings,” NRDC climate director David Hawkins told a Congressional committee in March. “Rather, the sector has not applied CCS to full exhaust streams because of a policy failure. Up to now, there has been no national requirement to limit carbon pollution from power plants.”

Is Capture the Future of Carbon?

If billions of dollars in federal investment doesn’t make CCS sound attractive, then maybe some regulations will.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) proposed caps on carbon emissions from newly built power plants last year, and proposed another set of caps for existing plants in June. Together, the proposed standards would bring domestic emissions 30 percent below 2005 levels over the next 15 years. The EPA expects to finalize the standards next year.

The regulations are at the center of the Obama administration’s “Clean Power Plan” for combatting climate change and, in turn, leaving President Obama with a global legacy he can hang his hat on.

The proposed standards would require newly built plants to run on advanced natural gas systems or install a CCS system to burn coal. The utility industry protested, arguing that CCS remains unproven and prohibitively expensive, but the EPA pointed to the struggling Kemper plant as evidence that it could be done.

The costs of upgrading existing power plants with CCS would drive some older plants out of business, so the EPA did not make any CCS requirements for the existing fleet, but the agency made it clear that carbon capture remains an option for meeting new emissions standards.

Some environmentalists agree that every option for reducing emissions should be on the table. But others point out that burning coal produces more than carbon dioxide, and CCS won’t do anything about the mercury, lead and toxic coal ash produced by power plants, old or new. The government, they argue, should be promoting renewables, not high-tech schemes to keep a dirty fossil fuel relevant.

“If we [had taken] the kind of money that has been put into clean coal and enhanced oil recovery and nuclear technology, if we had put that into wind and solar technologies that we are just coming around too, it wouldn’t be a question,” said Julian Boggs, the global warming director at Environment America.

Boggs said CCS still has to compete with renewables in the market, and as the cost of renewable energy continues to plummet, utilities may be wary about building massive new plants that burn coal.

Ash said the EPA’s regulations would not make CCS economically relevant because the “utilities don’t want anything to do with it” unless the government is paying for it. Clean coal experiments like CCS, he said, are more about politics than saving the planet.

“It’s allowed people from coal states, of which there are fewer and fewer, to pander to the idea that we can procrastinate in supporting policies that get us off of fossil fuels,” Ash said.

So, what would the hundreds of thousands of climate demonstrators who flooded the streets of New York think about the billions of dollars spent on a clean coal experiment with an uncertain future?

“I think people would be really irritated,” Ash said.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.