Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

During fall semester of 2010, I began taking students on five-day field trips to the Arizona–Mexico border. One part of these trips involves meeting with sound sculptor Glenn Weyant, who plays the border wall as a musical instrument. Weyant attaches contact microphones to the wall and plays it, sometimes bowing the steel structure with a cello bow, and other times playing it rhythmically with what he calls “instruments of mass percussion.”

There is a profound political dimension to Weyant’s sonic experimentation. He plays the wall, a steel barrier that was constructed in order to keep undocumented migrants out of the United States, and accordingly transforms this piece of military infrastructure—designed to separate two countries—into a musical instrument. Weyant’s wall music has been downloaded by people in over two hundred countries—his neo-avant-garde exercise in musical experimentation, in other words, brings people together and raises awareness of the militarization that is taking place on the US–Mexico border.

During these field trips Weyant gives us a live performance. He shows us his equipment and technique and he plays the wall for us (and sometimes for an additional audience of Border Patrol agents who come by to see what’s going on). Seen within the context of the field trip, my students—who by this point have met with deported people in Mexico and seen firsthand how the dynamic of privilege operates on the border—comprehend viscerally what, before the field trip, seemed to them merely a cerebral exercise of conceptual art. Two by two, Weyant then invites the students to choose implements (spoons, whisks, or pieces of metal, wood, or rubber) and to cross the border between audience and performer. We play in the largest group ensemble performances of the world’s largest, most expensive, and most lethal[1] musical instrument.

There are other instances during which music overlaps with politics on these field trips. We did not expect to hear music when we attended an Operation Streamline hearing—a legal proceeding in the Tucson Federal Courthouse during which seventy people per day, wearing handcuffs, chains, and ankle shackles, give up their right to a trial.[2] After meeting with a defense attorney for fifteen minutes in the morning, the detainees are then called up in groups of five to eight to appear before a judge. They respond to questions, often in chorus, plead guilty and then shuffle out for transport to for-profit prisons where they serve sentences of up to six months prior to deportation. On our most recent trip we observed one detainee intentionally jingling his chains rhythmically while he waited his turn in the courtroom. Essentially he was creating music with his chains while waiting to be sentenced. One student wondered in her journal why he would create sound from his shackles. Was he simply passing the time? Was this protest music? Perhaps creating music from his chains was a form of validating his existence in this identity-crushing place and situation, she wrote in her journal.

We also visit with recently deported people at a soup kitchen and a women’s shelter in Nogales, Sonora. It is disturbing, after having witnessed a hearing, to realize how these people have suffered through the dehumanizing process of Operation Streamline. Subsequently, on the US side of the border, we encountered migrants in the process of crossing the border while they were receiving medical treatment at a Red Cross-recognized humanitarian camp in the desert. Some of them had gone three days without food. Some of them were ill from drinking water from stock ponds for cattle. Some of the migrants told us that they thought they would die in the desert. Many of them will likely be detained by Border Patrol when they leave the camp and continue on their journey. They may be sent through Operation Stream and will subsequently be removed or deported.

In camp my students discover the humanity of people who we formerly referred to generically as “migrants.” Humanitarian volunteers tend to their wounds, feed them, hydrate them. Together we sit around a campfire with those who have enough energy. We take turns telling jokes, talking about our families, conditions in their countries (Honduras, Mexico and Guatemala), why they have come, and where they are going. Together we sing songs around the campfire. Sharing music by a fire under the stars is an organic activity during which I usually feel close to those around me. On our most recent trip, a migrant from Mexico, Joel, played a tambourine and smiled more than he had since we met him. I then passed my guitar to a Honduran named Óscar, who had had harrowing experiences in the borderlands. On an earlier attempt he carried a woman who had collapsed in the desert back across the border to Mexico; he saw people fall off of “la bestia,” a freight train in Mexico, and die; he saw another woman fall off the train and lose her legs.[3] Óscar told us that on a previous attempt to cross the border a fellow migrant died in the desert. Óscar’s group buried the body under rocks in the desert.

Here at the campfire we share music. Huddled around the fire we are no longer “migrants” and “students”; we have become friends—friends trying not to think about the differences imposed by our citizenship, our nationalities, and the privileges conferred to us by the place where we were born. To sing Woody Guthrie’s “This Land is Your Land” with these new friends in the middle of the desert brings lumps to our throats. Students have told me that the trip was a “life-changing” experience—they would never think about border issues, think of migrants, or even see themselves in the same way. These field trips have proven to be the most powerful pedagogical experiences that I have ever facilitated.[4]

Unfortunately, as much as I want to educate people about what is occurring on the border, I cannot take everyone on trips to the area. Since I am limited as to how many students I can bring to the border, I have sought ways to bring the border and the related humanitarian crisis to my students. In May of 2011, artist Shawn Skabelund and I (and collaborating members of the community) installed six thousand crosses in a quad on the campus of Northern Arizona University to honor and commemorate those that had died on the border.[5] This installation, 6,000 Bodies, made a significant impact on those who viewed it. Some students cried while contemplating the crosses. The installation was powerful, but it was still physically situated in a specific site, on a college campus in Flagstaff, Arizona, so people had to be present in this place in order to see the crosses. We needed a different medium—music—in order to dislodge the border crisis from a specific location and time.

Figure 1: 6,000 Bodies by Robert Neustadt, Shawn Skabelund and the community (May 1–5, 2011). Photo by Jeffrey Arnold Strang

Figure 1: 6,000 Bodies by Robert Neustadt, Shawn Skabelund and the community (May 1–5, 2011). Photo by Jeffrey Arnold Strang

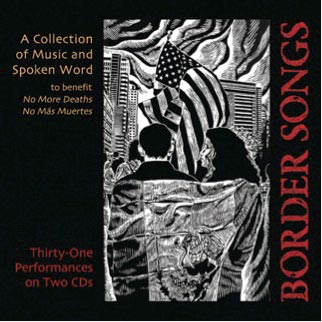

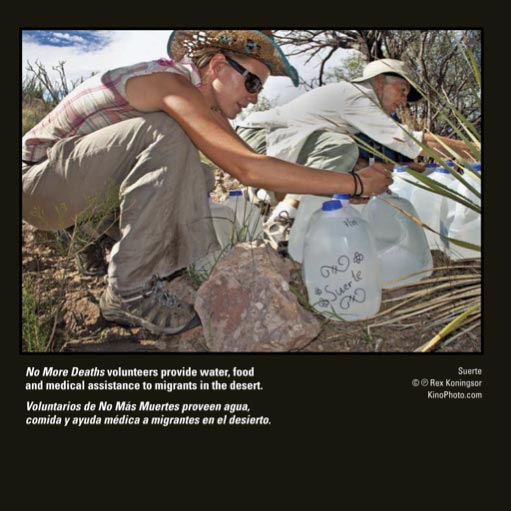

I coproduced the Border Songs CD, in part as a means to take advantage of the ability of music to transcend space. Music constitutes a powerful vehicle with which to raise awareness about the contemporary crisis on the border. The album, in many ways, is a musical journey that leads listeners to “see” some of the issues that we witness on our field trip to the border. At the same time, the Border Songs CD is literally raising money to save lives. My coproducer, Chuck Cheesman, and I fundraised to create the CD. All of the artists and producers donated their work, and the project is donating one hundred percent of the proceeds to No More Deaths / No Más Muertes, the volunteer organization with a base camp in the desert that we visited. No More Deaths places water in the desert and provides humanitarian aid to migrants in the Arizona desert and to recently deported people on the Mexican side of the desert. Each Border Songs album purchased provides twenty-nine gallons of water or the equivalent in medical supplies, food, or clothing to people in extreme need.

Figure 2: Border Songs (2012) album cover (original woodcut on cover, “Ni de aquí, ni de allá” by Raoul Deal), https://www.bordersongs.org.

Figure 2: Border Songs (2012) album cover (original woodcut on cover, “Ni de aquí, ni de allá” by Raoul Deal), https://www.bordersongs.org.

A double CD in English and Spanish, Border Songs is an extremely eclectic album that explores issues about the border and immigration through music and spoken word in a spectrum of diverse styles and genres. The diversity of musical and regional styles would serve in an introductory World Music course to teach musical genres including blues, corrido, cumbia, folk Americana, hip hop, Central American new song, rock, and wall!

Additionally, the Border Songs album could serve as a text in any number of courses—Border Studies, English Composition, Ethnic Studies, Latin American Studies, Literature, Spanish Language Skills—essentially any class in which students might explore the concepts of ethnicity, privilege, identity, and power. As a professor with a background in literature who teaches courses about the border and immigration, I often use song lyrics as texts in my classes. I assign students to write five short analyses (two to three pages) about five specific songs and/or spoken word pieces from the album. For these reaction papers I encourage students to observe how a specific song might highlight facts, realities, and perspectives about the situation on the US–Mexico border. Scott Ainslie’s song, “The Land That I Love,” for example, makes reference to the “push factors” that motivate Mexicans and Central Americans to attempt to cross the border:

I go to the market, in the town I was born,

It’s full of cheap clothes from China, and American corn.

But we have a small farm, that we water with tears.

How can we compete? The gringo farms are so big.

Now we cannot stay here.

The lyrics make reference to the fact that migrants seek work in the US not only because of endemic poverty but, more specifically, to flee from unsustainable conditions created by global trade agreements such as NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement). Upon implementing NAFTA in 1994, the US began to flood the Mexican economy with cheap government-subsidized corn, effectively driving millions of corn farmers (and others associated with corn production) off of their land.

Inspired by a true story of a woman who died while crossing the desert, the bridge to Ainslie’s plaintiff song points out the shallowness of economic theory in the face of human tragedy. “Who cares if your markets are free?” sings Ainslie, “Look what you’ve done to my wife and me. Who cares if your markets are free?”[6] Other songs also focus on the reluctance of migrants to cross the border. Eliza Gilkyson’s bilingual song “Vayan al norte” describes the sadness of life as an undocumented person living in the shadows—“Y pasamos por su mundo como sombras”—in the United States. In “Uphill (American Dream),” Chuck Cheesman sings of a lonely dishwasher in Chicago who sends money home to his wife and baby in Agua Prieta:

He carries her picture in his old leather wallet.

It sometimes brings tears, sometimes a smile.

It keeps you off balance

When you feel so alone,

And it’s hard to remember

The dream that made you leave home.

These songs bear witness to the reality that many undocumented people did not migrate by choice. Their lives in the US, furthermore, are by no means pleasant or easy. Luis, the dishwasher in Cheesman’s song, cannot even remember the American dream—“It’s hard to get going when it’s all uphill.”

In addition to assigning five reaction papers, I also ask students to post five brief commentaries on a discussion forum on Blackboard Learn about songs (or spoken word pieces) of their choice. For each of these posts I also ask students to comment on, or reply to, at least two of their peers’ posts. Allowing students to choose the songs that they want to discuss gives students a sense of ownership in the process of defining and directing the class. The process of choosing the pieces that they want to write about encourages students to explore the entire album, two hours of audio material, on their own. Having students reflect on each other’s comments, furthermore, prompts an electronic discussion that later overflows—it crosses the border—into the classroom and even into their everyday lives. In addition to observing the factual information communicated by the songs, students engage with the material aesthetically. Although my students are rarely music majors, they sometimes make perceptive observations regarding instrumental “Mexican-ness” (for example, the accordions incorporated by Scott Ainslie and Tom Russell, or the mariachi-style trumpets in Calexico’s “Across the Wire”). For some songs students note an apparent contradiction between an upbeat rhythm and lyrics that express profoundly sad stories (such as Calacas Blues’s “Nada que llorar”).

Other songs on the album, “Los mandados” (performed by Los Románticos), Lilo González’s, “Ningún ser humano es ilegal,” and Dúo Guardabarranco’s “Canción pequeña,” provide the opportunity to teach authentic Latin-American song forms: corrido(ballad), cumbia, and nueva canción (new song), respectively. Each of these songs explores the concept of national borders from a different perspective. “Los mandados” (written by Jorge Lerma) is a humorous corrido that expresses the viewpoint of a persistent migrant who ridicules the futile efforts of “La Migra” (the Border Patrol) to keep him out of the country.

Crucé el Río Grande nadandos

in importarme dos reales,

me echó “La Migra” pa’ fuera

y fui a caer a Nogales,

entré por otra frontera

y que me avientan pa’ Juárez.

I crossed the Río Grande swimming

not giving a darn

“La Migra” threw me back

and I landed in Nogales.

I entered through another border

Crossing, they booted me to Juárez

The song not only expresses the persistence of a border crosser who will not give up, it also makes reference to the Border Patrol’s controversial practice of deporting detained border crossers to different border towns, distant from the area where they were caught crossing. The Border Patrol uses the strategy of “lateral deportation” in an effort to break up the relationship between migrants and traffickers. Humanitarians argue that deporting people to random and often dangerous cities along the border, far from their families, is cruel, dangerous, and ineffective.[7]Like the protagonist of this song, deported migrants often attempt to cross the border again.

Lilo González’s cumbia “¡Ningún Ser Humano es Ilegal!” (No Human Being is Illegal) relates the singer’s autobiographical journey to the United States as an undocumented refugee fleeing the civil war in El Salvador during the 1980s. The song crosses various borders (from El Salvador to the US, from the past to the present) and underscores the difficulty of a migrant’s life in the US, where he feels trapped without options:

No puedo vivir aquí,

No puedo vivir allá

I cannot live here

I cannot live there

González’s song critiques the common practice of labeling undocumented people as “illegals” in the United States. “No Human Being Is Illegal” repeats the chorus in English, in this song written otherwise in Spanish. This chorus offers opportunity for the exploration of linguistic, national, and political borders. In class, we employ the song as a jumping off point to discuss immigration terminology, contrasting and debating the usage of terms such as “illegal,” “illegal alien,” “wetback,” “undocumented immigrant,” “migrant,” and “border crosser,” exploring how these terms carry distinct meanings and, at the same time, convey nuanced discursive biases with respect to immigration.

“Canción pequeña,” by Nicaraguan new-song group Dúo Guardabarranco, juxtaposes nature and humanity with political conflict: “Hace falta borrar las fronteras / La primavera no lleva documentos para pasar la aduana” (We need to erase the borders / Spring does not carry documents to go through customs), sings Katia Cardenal, in this chillingly beautiful “little song.” The song concludes by calling on us to transcend national divisions, to come together in one world: “Let’s weave all the flags together with so much cloth that they make one great sail for just one world.” This song facilitates our discussion of the relationship, or lack thereof, between geopolitical borders and nature. Before one has explored the concept critically, it is easy to think of borders as if they were natural divisions that have always existed. In the four years that I have been teaching about the border in Arizona, I can count on one hand the number of students who came to my class knowing the history of the US–Mexico border—a history that literally defined the contours of our state.[8] Through readings and films we also explore the cultural complexity that is hidden behind the binary border discourse—us versus them. Most of my students have never thought about how the history of indigenous peoples cannot fit neatly into a Mexico–US paradigm. The vast majority of my students have never even heard of the Tohono O’odham Nation, an indigenous nation in southern Arizona, whose Connecticut-sized homeland spans the international border.

Other songs cross borders musically. “Nada que llorar” (Nothing to do but cry), performed by Mexican–Costa Rican bandCalacas Blues and written by bandleader Alejandro Cardona, is a fast-tempo New Orleans-inflected blues that relates the story of a woman who leaves her children to seek work in the United States. The song’s protagonist leaves her belongings, family, and poverty behind and crosses the border to find work: “Busca un primo de su primo / Qué le encuentre un buen trabajo” (She looks for the cousin of her cousin / Who will find her a decent job). Ironically, the “dream” loses its luster on the US side of the border—to survive she finds herself working as a prostitute. Whereas the lyrics follow a woman who crosses the international border, the song simultaneously crosses musical borders. As mentioned above, “Nada que perder” is a blues tune, a musical form and harmonic structure that traditionally expresses the sadness of the African-American experience in the United States. This border-crossing blues expresses the misery and sadness of a woman forced to migrate as an economic refugee—only to find that her dream of a better life has vanished.

Sweet Honey In The Rock’s song, “Are We a Nation?” responds directly to Arizona’s anti-immigrant law, SB 1070, a law that transformed the immigration debate in the United States. Not only did the law reach the Supreme Court (parts of SB 1070 were struck down, other parts remain intact), but it also inspired copycat laws in thirty other states (including Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, South Carolina, Utah, and others). In addition to the contemporary theme of racial profiling, students observe the historical elements of the song. “Are We a Nation?” incorporates, for example, words extracted (and slightly changed) from the Declaration of Independence. We study “Are We a Nation?” fairly early in the semester and accompany the song with research on SB 1070 and a class debate on the parameters of the law as well as states’ rights and the federal government’s responsibility to set immigration policy.

Students in my class identified the song (and Sweet Honey In The Rock’s history) as part of the African American protest song tradition.[9]They also observed a link between Sweet Honey’s role in the Civil Rights movement and contemporary politics. In class we discussed whether the current movement for immigration reform is a new struggle or a new stage in the historical struggle for civil rights in the United States. To add depth to this conversation I incorporated journalistic accounts of contemporary immigration protests that are breaking out all over the United States. As a result of their age, many students, particularly non-minority students, consider the Civil Rights movement to be “history.” To give them a complete view of the political spectrum, I had them read anti-immigration reform articles, ranging from pieces written by conservative thinkers to examples of pure xenophobic vitriol. My students were surprised to realize that for many the struggle for civil rights continues into the twenty-first century.

We spend considerable time in the course studying the little-known details of the humanitarian crisis on the border. Students are stunned to learn that since 1994 over seven thousand human remains have been found in the borderlands and that this number only counts the dead whose remains have been found.[10] As the Border Songs booklet states, experts in the field estimate the number of border crossers who have actually died on the border to be between two and ten times the number encountered. We also read “A Continued Humanitarian Crisis at the Border: Undocumented Border Crosser Deaths Recorded by the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner 1990–2012,” (published jointly by the Binational Migration Institute and the University of Arizona in June 2013), detailing statistical changes in border crosser deaths over the years.[11] This study demonstrates how this crisis is directly linked to US Government border security strategies and enforcement including the wall and the resulting “funnel effect.”[12]

We also read The Death of Josseline: Immigration Stories from the Arizona Borderlands by Margaret Regan—a book that explores the border scenario from a multitude of different perspectives (migrants, Border Patrol, landowners, environmentalists, medical examiners, and humanitarians). The book begins with the story of the death of Josseline, a fourteen-year-old girl from El Salvador who was abandoned in the desert while trying to reach her mother in Los Angeles. The CD booklet presents a photograph of a shrine in the desert where she died. My students become noticeably affected while contemplating this photograph. They are shocked when they realize that Josseline would have been their age had she lived.

A piece on Border Songs, a rock tune, “Sunset Limited,” performed by Lakesigns, was written by lead vocalist Will Gosner, Margaret Regan’s son. Gosner assisted his mother while she was conducting much of the research for the book. The song alludes to the death of Josseline, specifically to the horror of finding the remains of this dead child in the desert: “But I know something else / And that’s the sound of the scream / When they found her body lying / By the edge of the stream.”

In readings and class discussions we explore and debate No More Deaths’ humanitarian mission—“to end death and suffering in the US/Mexico borderlands.”[13] Shortly after discovering Josseline’s remains, No More Deaths volunteer Dan Millis received a littering citation for placing sealed gallon jugs of water along migrant trails in the Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge (BANWR). We discuss the legal complexities of the issue, including the question of whether No More Deaths is encouraging and/or facilitating illegal immigration by providing water. Given the immensity of the desert borderlands, and the fact that migrants have no idea where they might find water, most agree that No More Deaths by no means encourages undocumented immigration. Millis refused to pay the fine, went to court, and was convicted of littering. His case was later overturned by the US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.[14] No More Deaths has won all twenty-seven of its legal cases, showing consistently that it is indeed legal to provide humanitarian aid.[15]

Ted Warmbrand’s song, “Who’s the Criminal Here?,” arises from the tradition of 1960s-style protest folk music. The song provides the opportunity for students to engage with the thorny concept of our ethical and moral responsibilities, especially when these might risk breaking the law (or breaking someone’s interpretation of the law). The song was inspired by a case from 2005 when two volunteers from No More Deaths, Daniel Strauss and Shanti Sellz, were arrested for driving undocumented border crossers to a hospital in Tucson. The volunteers had consulted with No More Deaths’ medical team and believed that these people were in danger of dying. In the aftermath of this case, No More Deaths has changed their protocol and now calls 911 when they encounter people with urgent medical need. Given the situation, nevertheless, most people would agree that Strauss and Sellz acted ethically in attempting to save these people’s lives. Warmbrand’s lyrics invert the notion of criminal responsibility:

I can shut my eyes and turn away

Shut my mouth—nothing to say

Should someone die in my desert today

Who’s the criminal here?

In class I combine discussion of this song with journalistic articles about the case. Strauss and Sellz were charged with transporting and conspiring to transport “illegal aliens in furtherance of their illegal presence,” and faced fifteen years in prison and a $500,000 fine. The judge dismissed all charges on September 1, 2006. In 2007, Sellz and Strauss were given a $20,000 award, the Óscar Romero Award for Human Rights by the Rothko Chapel. Warmbrand’s tune has taken on the character of an anthem in the humanitarian community—especially for activist groups like No More Deaths who defiantly assert, “Humanitarian aid is never a crime!”

We also read Luis Alberto Urrea’s Devil’s Highway (2004), a book that provides students with a horrifically vivid account, based on a true story, of the deaths of fourteen border crossers on the Tohono O’odham reservation. Urrea describes, in detail, the stages of dying of hyperthermia in the desert. The writer mentions that Calexico’s song “Across the Wire” (included on Border Songs) lent him “moral support” while he was writing the book (226). In circular fashion, the Calexico song takes its title from Urrea’s first book, Across the Wire: Life and Hard Times on the Mexican Border (1993). The haunting lyrics of “Across the Wire” narrate the border crossing of two brothers. The song describes the journey with dark metaphors alluding to the myth of the founding and death of Tenochtitlan:

Spotted an eagle in the middle of a lake

resting on cactus, feasting on snakes

but the waters recede as the

dump closes in, revealing a whole lake

of sleeping children.

Though abstract, this connection between Tenochtitlan and migrant death points to the fact that many migrants, indigent people who travel from southern Mexico and Central America, are of indigenous descent. The Devil’s Highway account dovetails with “Across the Wire” and other songs on Border Songs, particularly with pieces that call attention to the tragedy of migrant deaths. Poems on the album by Mario Bencastro and Raúl Zurita underscore the anonymity of migrants who die and disappear in the desert. Students are dumbstruck to learn that the morgue in Tucson currently houses nearly nine hundred unidentified human remains from border crossers.[16]

The clandestine aspect of human smuggling results in death even after migrants have made it some distance from the border. Joel Rafael’s song “Sierra Blanca Massacre” tells the true story of a group of migrants who suffocated to death while locked in a boxcar:

These are some words from the victims found

Inside a boxcar in a small Texas town

Locked from the outside in spite of their pleas

Inside was a hundred and thirty degrees

Inside was a hundred and thirty degrees

The CD brings students a new heightened awareness regarding conditions on the border and how our immigration policies result in death throughout the country. This year, a group of migrants were found unconscious in the back of a U-Haul truck near Picacho Peak, just north of Tucson, suffering from extreme heat.[17] Reading the details from the case (one of the migrants subsequently died) makes one realize that Rafael’s “Sierra Blanca Massacre” is really about more than one specific incident. “Sierra Blanca Massacre” bears witness, musically, to tragedies that take place repeatedly throughout the United States. Coincidentally, at the time I was writing this essay, the local newspaper reported that a van carrying as many as twenty undocumented migrants overturned on the interstate near Flagstaff (270 miles north of the border), with some fleeing and fifteen taken to the hospital.[18] My students continually remark that they had no idea of the level of suffering and death associated with undocumented immigration until researching the issue for class.

Students identified Tom Russell’s “Who’s Gonna Build Your Wall?” with country music, a traditionally conservative genre with regard to politics, and noted the humor with which the songwriter critiques US immigration policies. One student discovered, when researching Russell’s sarcastic dig at US hypocrisy— “But if Uncle Sam sends the illegals home / Who’s gonna build the wall?”—that there indeed have been cases of undocumented people working on the border wall construction sites.[19] Studying the song in class leads us to learn about the double irony of the wall. While border enforcement does not keep people from entering the country without documents (as is evidenced by the fact there are some eleven million undocumented people currently living in the US), the border wall encloses undocumented people within the United States. In addition to making the journey across the border more costly, dangerous, and lethal, the wall has altered the pattern of undocumented immigration, encouraging people to remain in the US rather than risk migrating cyclically between the two countries (as used to be common). The wall has also resulted in more women and children crossing the border, bringing up the issue of family (re)unification, such as the tragic case of Josseline. We complement our discussion with readings about the current debate over immigration reform.

Russell’s lyrics also highlight players in our national border controversy that my students had not yet discovered. None of my students, for example, had heard of the Minute Men vigilante groups that Russell sings of:

There’s minute men in little pick-up trucks

Who declared their own dang war

Subsequently, we watched a number of documentary films that interviewed Minute Men. According to Minute Man Civil Defense Corps founder Chris Simcox (currently in prison), the Minute Man movement played a decisive role in getting the US government to build the wall. This is merely one example of how a single detail from a song can provide a springboard for students to learn about important contemporary issues.

In addition to working with the audio, lyrics, and spoken word texts, I also make use of the photographs and art from the Border Songs booklet as teaching tools. I ask students to bring the booklet to class on certain days and have them discuss and react in pairs to a specific image. In general, I often find that students have difficulty distinguishing between description, analysis, and opinion, so I use these photographs as writing prompts to demonstrate the difference between these three registers. In a Spanish composition class I asked students to write three separate paragraphs in response to the photograph from the album booklet of a baby shoe in the desert.

Figure 3: Border Songs booklet, page 7.

Figure 3: Border Songs booklet, page 7.

Students wrote an objective and detailed description, an analysis of what the photograph might exemplify in the context of the album and a subjective reaction to the image. This type of exercise would work with virtually any of the photographs from the booklet.

Border Songs provides the opportunity for students to explore and examine the US–Mexico border and immigration from anywhere. Obviously, listeners’ musical taste will vary as will their preferences for pieces on the album. Many students will relate rhythmically to Pachuco and Classik’s hip hop song in Spanish, “Somos Mexicanos.” The song’s lyrics communicate the experience of a young person living in the United States without documents—a topic that appears frequently in the press in the context of debates about the DREAM Act and President Obama’s recent DACA program (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals).

The Border Songs compilation is an audio anthology that allows the listeners to see, and hear, much of what is occurring on the border and within our country from a variety of different perspectives—and to explore critically the consequences of current immigration policy and border enforcement strategies. The album features a spectrum of musical genres and styles including songs that will break one’s heart, and others that will make a listener laugh. Some of the musicians, such as Amos Lee, Calexico, and Michael Franti will be familiar to many of today’s students. The lyrics of Michael Franti and Spearhead’s song, “Hello, Bonjour,” challenge the very concept of political borders.

So don’t tell a man that he can’t come here

’Cause he got brown eyes and a wavy kind of hair

Franti’s “Hello, Bonjour” uses a reggae/ska idiom to move beyond politics, proclaiming that all humans share the same earth:

I don’t need a passport to walk on this earth

Anywhere I go ’cause I was made of this earth.

Border Songs also includes important artists that many of today’s students may not know. Students have asked me if Pete Seeger, who recently passed away at ninety-four years of age, is Bob Seger’s son! Seeger’s contribution to the album, “My Rainbow Race,” opens the door to discussions of the historical Peace Movement and analyses of progressive contemporary discourse and multiculturalism. In April 2012, after a right-wing extremist murdered some seventy-seven people in Norway, forty thousand people joined together to sing “My Rainbow Race” in Oslo.[20] In the version of the song on Border Songs a choral section reiterates, in musical unison, the concept of unity.

I began this essay with a description of Glenn Weyant playing the border wall with my students. In 2010, Weyant visited the border with poet Margaret Randall, each of them interpreting the wall in their own way. On the album we blended one of Weyant’s sound sculptures, “Droneland Security,” with a recording of Randall reading “Offended Turf,” a poem she wrote after seeing the wall and listening to Weyant play it. “We are making music here,” writes Randall:

You with your cello bow,

percussion implements

and contact mike.

Me with the words I coax

from walls and fences everywhere.

Randall’s poem reflects on the offensive misuse of power with which our militarized border violates the earth, humans, and animals alike. Weyant, meanwhile, reimagines this barrier, built for exclusion, and transforms it into music. In a sense, this combination of Randall’s and Weyant’s “songs” represents our goal for the larger Border Songs project. As Randall writes, the project is an effort to use poetry and music to do good: “We’re taking a chance our vibrations will change these molecules of hate.” In the short term, as I mentioned earlier, the proceeds from the album go to No More Deaths and in this way continue to reduce death and suffering in the borderlands. The album carries with it an equally important pedagogical goal. Ultimately, it is our hope that Border Songs, this eclectic and diverse musical representation of the border and its politics, will help raise awareness and knowledge about the border throughout the country and world—awareness that will bring people together, and knowledge that will someday help to improve the catastrophic conditions that we continue to see today.

Figure 4: Border Songs booklet, page 18.

Figure 4: Border Songs booklet, page 18.

Notes:

1. The US government began the construction of walls on the border in 1994 around the time when the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) went into effect. Expecting an increase in undocumented migration as a consequence of NAFTA, the US began constructing walls to seal the easy-to-cross urban areas of El Paso, San Diego, and Nogales, thus funneling undocumented migrants through the harsh, remote, and deadly areas of the Arizona desert. Since 1994, according to the Coalición de Derechos Humanos, over seven thousand bodies have been found in the borderlands, the majority of these in Arizona.

2. For a recent article about Operation Streamline, see Fernanda Santos, “Detainees Sentenced in Seconds in ‘Streamline’ Justice on Border,” New York Times, February 11, 2014.

3. Thousands of the most impoverished Central American migrants ride on top of freight trains to travel through Mexico. They call the train “la bestia” (the beast) presumably because of the danger of falling or getting thrown off the train and being sucked under the wheels. For a film that follows the experiences of migrant children on the trains, see Rebecca Cammisa’s powerful documentary film Which Way Home (2009).

4. I have written about some of these field trip experiences in more detail in an article in UTNE Reader, “Looking Beyond the Wall: Encountering the Humanitarian Crisis of Border Politics,” May/June 2013.

5. In 2011, at the time of this installation, experts reported that over six thousand human remains had been found on the border since 1994. Now, in 2014, over seven thousand dead have been encountered.

6. For Ainslie’s description of the story that inspired him to write the song, and to a see a video that he produced to illustrate his song, see: https://cattailmusic.com/theborder/.

7. On Lateral Deportation, see Nick Miroff, “Lateral Deportation: Migrants Crossing the Mexican Border Fear a Trip Sideways,” Washington Post, February 12, 2013. See also, the “Lateral Repatriation Factsheet” published by the humanitarian group No More Deaths.

8. The US forced Mexico to sell over half of its territory for $15 million in 1848 in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo as part of the conclusion of the Mexican–American War (known in Mexico as the “American Invasion”). Subsequently, the Gadsden Purchase (also known as the Mesilla Treaty), which was finalized in 1854, transferred a piece of southern Arizona and New Mexico to the United States, setting the international boundary where it stands today.

9. Sweet Honey released a video with a (slightly different) version of the song.

10. Kat Rodríguez (Coalición de Derechos Humanos), personal communication, March 7, 2013.

11. https://bmi.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/border_deaths_final_web.pdf.

12. This article historicizes the humanitarian crisis on the border, even breaking down migrant death statistics into three discreet periods: “Pre-funnel effect” (1990–1999), “Early Funnel Effect” (2000–2005) and “Late Funnel Effect” (2006–2012).

13. For information on No More Deaths / No más muertes, see the organization’s web page: https://www.nomoredeaths.org.

14. For a journalistic account of Millis’s case after it was overturned, see Carol J. Williams, “Border Activist’s Littering Conviction Is Overturned,” Los Angeles Times, September 3, 2010.

15. Margo Cowan (NMD attorney) via John Fife (NMD cofounder), personal communication, April 8, 2014.

16. Personal communication, Robin Reineke, Director of the Colibrí Center for Human Rights, June 12, 2014. See also Binational Migration Institute, “A Continued Humanitarian Crisis,” 14n12.

17. About the case of migrants suffering from heat who were discovered near Picacho Peak.

18. See “15 undocumented immigrants injured in crash near Flagstaff” by Eric Betz (Jan 25, 2014) in the Arizona Daily Sun.

19. Scott Horsley, “Border Fence Firm Snared for Hiring Illegal Workers,” All Things Considered, NPR, December 14, 2006. “Fence Firm Hired Illegals,” Washington Times, March 30, 2007.

20. On the episode of forty thousand people joining together to sing Pete Seeger’s “My Rainbow Race” in Oslo, see Valeria Criscione, “Breivik Slam on ‘Rainbow’ Song an Insult to Far for Norwegians,” Christian Science Monitor, April 26, 2012.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.