Bob Moses was a quiet political giant. Sometimes he spoke so softly you could barely hear him. But it was always worth your while to listen carefully to every word. I met and talked with Bob many times over a 30-year period, and was always deeply inspired by his wisdom, his grace, his refusal to be rushed or consumed by the urgencies of the moment, and his love of justice. He was consistent in his practice, committed to a clear set of values and courageous in his choices.

Bob Moses was lesser known than many of the luminary figures of the Civil Rights and Black Power era, but his vision, his impact and his example were profound. And he actually preferred to be in the background rather than in the limelight.

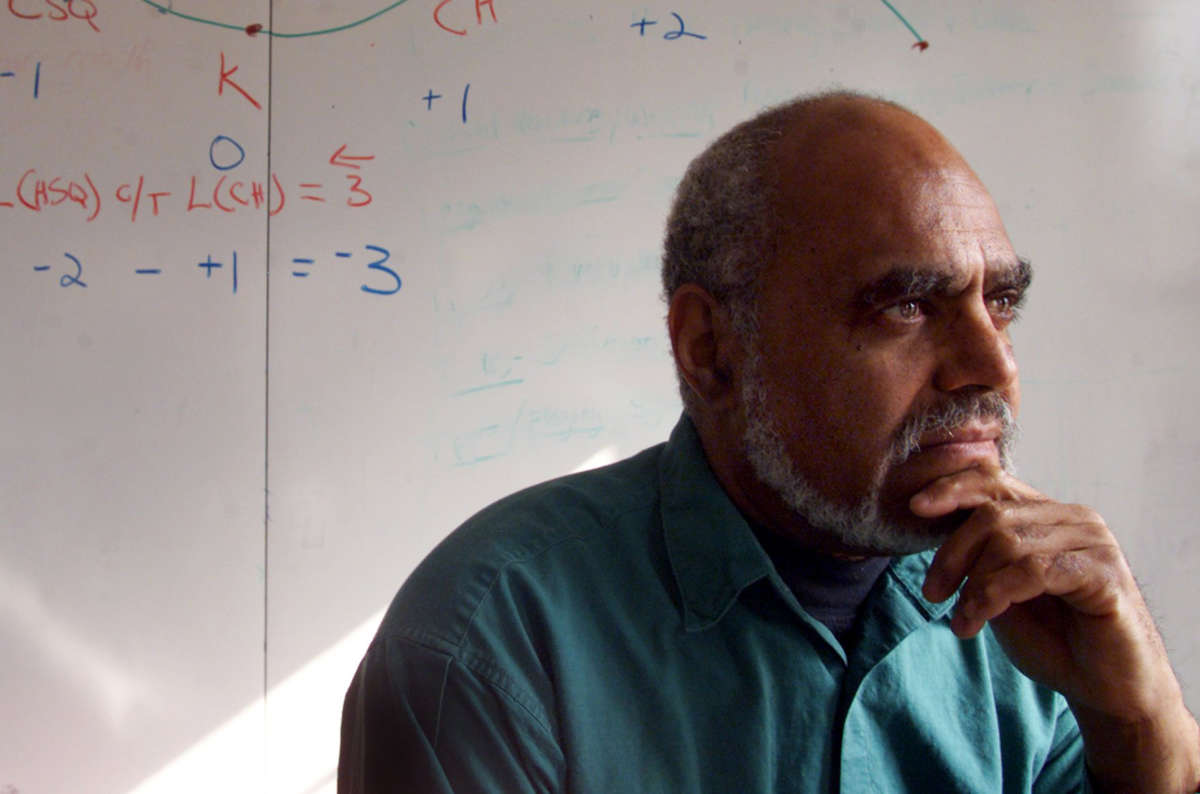

Born in Harlem, New York, in 1935 to Black working-class parents, Bob finished college and began working in education. A math teacher by profession, he was also a philosopher. He studied philosophy at Harvard but it was not an academic exercise for him. He thought deeply and profoundly about our moral obligation as human beings to do good on the planet. He read the French-Algerian philosopher Albert Camus as a young man and was deeply influenced by Camus’s moral challenges.

In the summer of 1960, Bob was profoundly affected by the Black Freedom struggle he saw unfolding in the U.S. South and looked for ways he could contribute. He spent some time hanging around in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) office in New York, trying to get a foot in the door. He eventually obtained a letter of introduction from pacifist progressive organizer and intellectual Bayard Rustin, one of the few prominent gay Black leaders in the movement’s inner circle at the time. The letter led him to Bayard’s old friend and collaborator, legendary movement sage Ella Baker, then leading the SCLC office in Atlanta. She saw something in Bob and he found something special in her. Thirty years his elder, Baker reminded Bob of his father, a blue-collar worker with a love of books and justice. Baker’s humility, her grassroots radical democratic ideas and her anti-elitism resonated for Bob. They began a lifelong friendship and comradeship.

Bob quit his job in New York, and migrated South to become an organizer. He was introduced to Mississippi local organizers Amzie Moore and C.C. Bryant and began to build deep ties. Bob eventually joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and became one of the organization’s most influential and respected “leaders.” I place this word in quotes because the notion of a “leader” suggested a kind of hierarchy that Bob eschewed. He often viewed charismatic leaders as condescending and self-promoting. In contrast, Bob recognized Baker as a revered movement teacher, “fundi” in Swahili, and a political mentor. “What Ella Baker did for us, we did for the people of Mississippi,” Bob once remarked, meaning Baker respectfully supported and enabled the work of young activists in SNCC but never dominated or usurped the mantle of leadership. That was the ethos that guided Bob’s work with the sharecroppers, maids, teachers and small business owners in Mississippi in dangerous voting rights campaigns, and in the formation of their own organizations, like the historic Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP).

After the National Democratic Party leadership refused to seat the full MFDP delegation at its 1964 Atlantic City convention, deferring to the objections of the all-white official delegation instead, Bob and many others were disillusioned but not entirely surprised. At the same time, Bob was concerned that people in the movement were too invested in individual leaders, including him. He wanted none of the celebrity that was coming his way. He resigned from SNCC and eventually moved to Africa, where he taught math in Tanzania for nearly a decade.

Upon his return from Tanzania, Bob resumed his work as an educator, this time with new insights, pedagogies and commitments. He saw ineffective and inaccessible math education as a roadblock to Black progress, and pioneered new methods of teaching through his now widely acclaimed “Algebra Project,” which he began in Massachusetts, and which he and others subsequently replicated in Mississippi. He wrote about his work in a book he co-authored with former SNCC comrade Charlie Cobb, entitled: Radical Equations: Civil Rights from Mississippi to the Algebra Project, in which they trace the roots of the Algebra Project in the SNCC’s freedom schools in Mississippi.

Some tributes to Bob Moses describe him narrowly as an educator and voting rights advocate. That sells him short. Bob was so much more than that. At every turn, he sought to stand on the right side of history, and to stand with dignity and integrity. He not only fought for Black people to have the right to vote, and for Black children to have the right to learn math, he also spoke out against war and imperialism. Bob was a passionate opponent of the U.S. war in Vietnam and subsequent wars. He was an advocate for racial justice in the U.S. and self-determination around the world.

One of the last times I saw Bob in person was at an activist gathering in upstate New York about six years ago. He had not been well, but made the trip anyway. It was an intergenerational gathering with many of the young people who had been leaders of the growing Black Lives Matter movement, the newly launched Movement for Black Lives coalition, and the Ferguson, Missouri, uprising. As a part of the introductions, we went around the room and were asked to say our names and preferred pronouns. When it was Bob’s turn, he said, “My name is Bob Moses, (pause) and my preferred pronoun is WE.” He really meant it. He had spent his entire adult life fighting for “us,” embedding himself in the collective struggle for Black freedom and human liberation.

Rest in power, sweet brother. WE will do our best to carry on, following your example, inspired and fueled by your lifelong commitments.

Speaking against the authoritarian crackdown

In the midst of a nationwide attack on civil liberties, Truthout urgently needs your help.

Journalism is a critical tool in the fight against Trump and his extremist agenda. The right wing knows this — that’s why they’ve taken over many legacy media publications.

But we won’t let truth be replaced by propaganda. As the Trump administration works to silence dissent, please support nonprofit independent journalism. Truthout is almost entirely funded by individual giving, so a one-time or monthly donation goes a long way. Click below to sustain our work.