Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

To the mainstream press, Sekou Odinga was a fearsome Black Panther in the infamous 1969 Panther 21 case, a member of the Black Liberation Army and the underground strategist responsible for the 1979 prison escape of Assata Shakur. To the Black liberation movement, Sekou was a community organizer who helped establish the Panthers’ International Section and a hero who served over 33 years in maximum-security prisons for militant actions to free his people.

Prison is where Sekou met his wife, dequi kioni-sadiki, a Black liberation activist and chair of the Malcolm X Commemoration Committee, who, as part of her political work, had come to visit this revolutionary. Looking back, dequi reflects, “I juxtapose how the state sees Sekou, and how movement people think of him as a legendary freedom fighter. But to me, he’s such a man of peace.”

Sekou and dequi didn’t immediately fall in love, dequi remembers: “It was more of a growing into.” They were married in a New York state prison visiting room in 2011, three years before Sekou was released on parole in 2014. Then, for a little over nine years, they shared a life together, in relative freedom, traveling, seeing friends, listening to music.

Sekou Odinga died on January 12 this year in a Manhattan hospital after months of paralysis caused by a virulent systemic infection. His memorial service on June 8 drew hundreds of mourners to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and thousands more online.

I was their friend. Years ago, I was a guest at a party dequi gave to celebrate her marriage, long before she knew Sekou would be released. I also interviewed dequi for Truthout in 2014 about what it’s like to love somebody behind bars. And, because I’ve never known dequi when Sekou wasn’t a part of her life, I wanted to interview her again. I began by going over old ground, asking dequi why she decided to marry Sekou, knowing that he might never get out…

dequi kioni-sadiki: I don’t know. I’ve never been a woman who felt like she had to have a man, and that’s served me well. Maybe it was — I don’t want to say naivete — I just believed he was going to come home. A lot of people didn’t.

I can’t say what moment led me to tell him, “OK, I’ll marry you.” I just loved him, despite him being in prison. And I was willing to be with him, however that was.

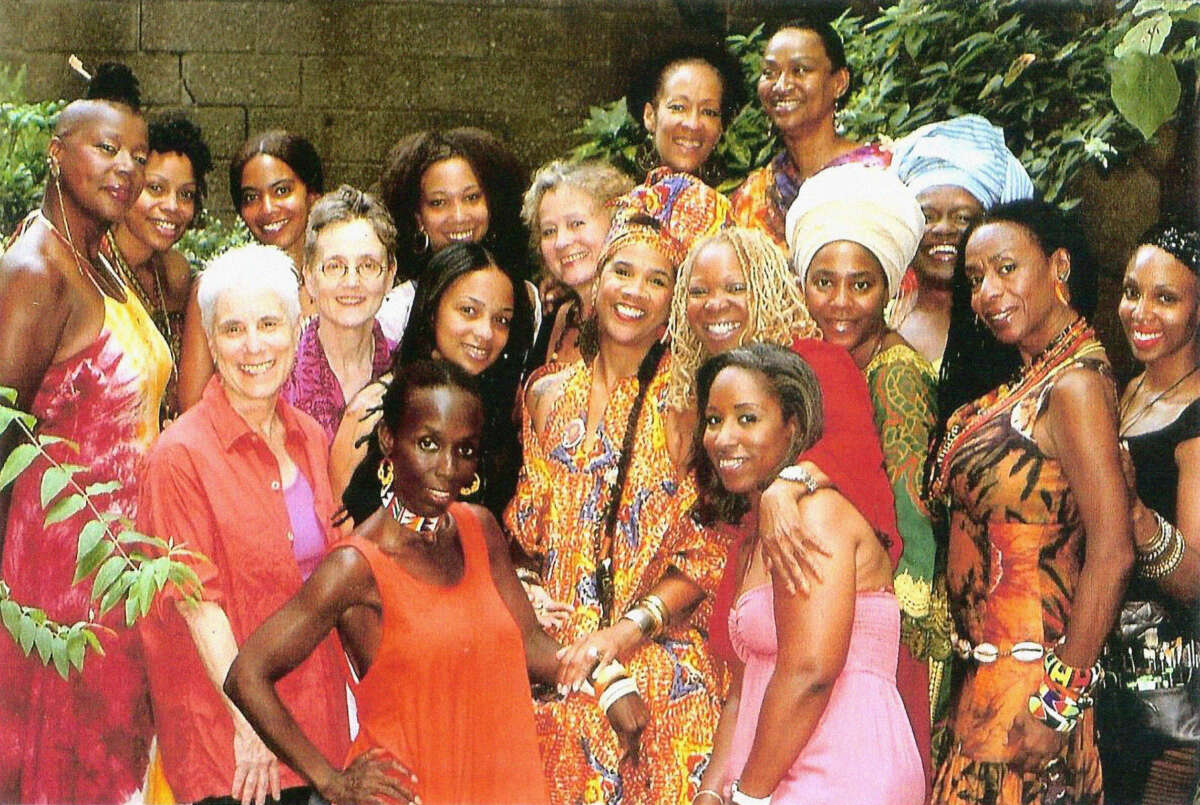

susie day: After you and Sekou married, you gave a celebration for yourself at a friend’s house in Brooklyn. It was one of the bravest, most brilliant things I’ve seen anybody do. Obviously, Sekou couldn’t be there, but you asked your women friends to show up, and everybody dressed to the nines. You had on this amazing headdress…

I remember calling it “Women Who Help Me Fly.” Women have long been central to my life. They support me, they nurture me. Sekou couldn’t be there, so I celebrated with the people who are important to me.

Also, weddings are a cause of celebration, right? I didn’t feel the state should take that away from me. I wanted to celebrate that the prison system — like the slave system — couldn’t crush our ability to be together and see beyond the bars. The circumstances weren’t the best, but it was joyous — I met the love of my life, a perfect match for me. That didn’t mean that we were perfect…

But I’d have felt so sad, being at this party alone, without my partner.

Interesting, you say alone. Now I feel alone. When Sekou was alive — even when he was in prison — I didn’t feel alone. I felt protected, safe. I mean… we didn’t always agree on stuff, but we shared the same values. After he got out, we had to combine our lives — his 33 years in prison, and my years of being a single woman, living on my own. You know, when two people come together, you bring in both your lives, and we had to get adjusted.

Sounds like a relationship to me.

Yeah. We also watched a lot of movies; went to listen to live music. We liked jazz; Monk, Parker. There was a Temptations song that Sekou sang to me all the time: “My love is growing every day”… I forget the words. He used to write that in his letters from prison. When I listen to Otis Redding’s “These Arms of Mine,” I hear Sekou singing that. And “Tennessee Whiskey”? He’s as smooth as Tennessee whiskey; sweet as strawberry wine…

When people fussed during COVID and couples got sick of each other? We never had that. I enjoyed his company. We laughed. I used to tell him: I don’t just love you; I like you. You’re funny. I was annoyed with him at times, and he was annoyed with me. But he could always make me laugh.

Did your politics change, being involved with Sekou?

I learned more about different people in the Black Liberation Army, and it may have made me more fiercely determined on the side of armed resistance. But what I really learned is how Sekou was able to endure for years with almost nothing. It made me see that I had a semi-privileged life. I used to tell him, “You don’t have to save food like that; you’re not in prison anymore.” But I kept seeing him making do, never buying himself anything. I was never penniless, but when Sekou was underground, he didn’t have any money.

When Sekou first came home, he went grocery shopping with me. They totaled the price, and he let out this huge scream. He couldn’t believe how much stuff costs. Of course, I was buying everything organic. I said, “We got to undo 33 years of piss-poor nutrition.” And he was like, “Man, things cost so much!” He wouldn’t go shopping with me again.

I also told him that he was not a feminist. “You are truly against women’s oppression as it relates to capitalism, colonialism, imperialism,” I said. “But there’s always food in the house — if you was a feminist, you’d cook. The fact that you will not eat all day unless I cook, tells me something.” Actually, I’m not very domestic. We went out to eat a lot.

This time last year, you had no idea how your lives would change.

Maybe last July or August, Sekou began saying his legs bothered him. Then his neck. He thought it was just arthritis. I said, “You really need to get that checked.” He didn’t, and by the time September rolled around, he was in excruciating pain. On September 1, we went to the emergency room. That’s when we found out he had the urinary tract infection.

Two days later, he was in the hospital?

Yes. The surgeon told me that the UTI had traveled into Sekou’s kidneys, his blood and culminated in an abscess on his spinal cord. That evening, they did emergency surgery, and found that some of the bones had weakened or disintegrated. They had to take out a couple of inches of vertebrae and put in some rods to strengthen his spine.

He came through the surgery. That’s when they told us they didn’t get the whole abscess; it would have been too dangerous.

Why do you think Sekou took so long to see a doctor?

A lot of it is the self-diagnosis most of us tend to do. I also think it has to do with living decades in prison. Sekou just wouldn’t let his body break down behind the walls. Incarcerated people usually just ignore shit, because you know it’s not going to be treated.

This is a man that don’t ever sit with his back to the door. I remember him talking about when he was in prison, being in horrible pain. And just scrunching down in the yard, with his back against the wall, so he could see everything, but not let anybody know he was in pain. That was the arthritis.

The doctors said Sekou might get better, but that he’d need to be in medical facilities for months, with dedicated — and incredibly expensive — nurses and attendants. You couldn’t possibly have done all this alone. So you asked for help from your community of friends, activists, other former prisoners.

Because he couldn’t move, he was vulnerable. Sekou said, “When I open up my eyes, I want to see someone I know and trust. So I want to ask brothers in particular — because sisters always come through — but I want to remind brothers about being men and that we should take care of each other.”

So this whole infrastructure developed, where people volunteered, “I’ll do this or that day; take this or that shift.” That’s how the collective came to be. We were an impromptu collection of friends, family, comrades, even lawyers, from different parts of Sekou’s life, and we’re still together. People got up at 5:00 in the morning to get to the hospital at 7:00. People fed him and sat there with him. They gave up their beds at night to sleep on a hard chair next to Sekou. It was his vision about community.

I did a few shifts. And every time, I was knocked out by how centered and kind he was — even paralyzed, how he kept it together.

That’s what I saw. I lived with him. He prayed five times a day, did Ramadan, even when he wasn’t feeling good. One thing people had always asked him was, “How did you do that time?” And his answer was always, “My faith.”

He’s a deeply spiritual man. But I saw it in a whole nother up close and personal way, from September until January 12. I saw how his faith enabled him to be present, to not take it out on people or feel sorry for himself.

We spent a lot of time together in the hospital alone. Sometimes it was just us looking at each other, the unspoken. I wanted always to be there, because those nurses, they never knew how to position him in the bed, to keep his legs up and the swelling down; they just never got that shit right.

A couple of times, he caught me crying. He said, “What’s the matter? You don’t think I’m gonna get better?” I’m like, “No, I’m crying because I feel like I’m more worried about you than you are of you.” He said, “Well, I’m gonna work hard to get my strength back. This is just what I have to deal with.” And I told him that I would never leave his side, that we were in it together. So yeah, I wouldn’t have been as stoic and put together. I really saw in those months what he meant about his faith.

Then in January, they came to tell you the prognosis — that all this was not working.

I already knew that was going to be it. Even though Sekou was on a ventilator by then and couldn’t speak, he could shake his head “yes” or “no.” He was still a decision maker. We decided, and at 10:30, the morning of January 10, we took him off the ventilator.

We had talked about death. He said he wanted to go first. But I never imagined that if he went first, I’d be by myself. He just said, “Whenever you’re ready, baby, because I’m ready.”

I said, “I’ll never be ready. But I will respect your decision.” That was a moment where we were in the room by ourselves.

And these days, how are you doing?

I don’t lie to people and say I’m OK. But I’m functioning. I get up every day, I take a shower, make up the bed. Every day’s different; I never know what the trigger will be. I was in Best Buy the other day, and they were playing Tammi Terrell. I just started crying, because Sekou loved Tammi. Also, Sekou’s thing was, he eats a piece of candy, he takes the wrapper, he makes a little bowtie out of it. I still find those all over the place. What’s that thing when people are in recovery? I take it one day at a time. Because I do feel alone. I feel less safe in the world.

Do you want to mention Sekou’s memoir to be published by The New Press?

Yeah, he worked on it with the writer asha bandele. There’s no publication date yet, but it’s gonna be beautiful. He chose wisely, doing it with asha. She’s a beautiful writer.

I used to tell him, “You don’t just want political people, you want everybody to read this book. Like, you’re not some militant who said, ‘Pick up the gun.’ This is a history lesson about the Black freedom struggle, but also about your life.” His father came from a self-sustaining town, founded by Black people. It’s these things — seen and unseen — that strengthen a man like Sekou. This book will put Sekou’s story into the context of: This has been going on since we were kidnapped.

So I feel enriched because I met Sekou, and we grew into love. I’m thankful that Sekou was home for nine years — because how many of our folks never got that? But I’m also tired of waking up every day without him. Every time I have to tell somebody that he passed away, I feel like I’m struck by lightning.

This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to raise $38,000 in the next 6 days. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.