Did you know that Truthout is a nonprofit and independently funded by readers like you? If you value what we do, please support our work with a donation.

Greg Palast reviews the extraordinary career of Venezuelan President and Robin Hood figure Hugo Chavez, how he has cheated kidnap and assassination and may yet cheat death by maintaining his accomplishments.

Venezuelan President Chavez once asked me why the US elite wanted to kill him. My dear Hugo: It’s the oil. And it’s the Koch Brothers – and it’s the ketchup.

[As a purgative for the crappola fed to Americans about Chavez, my foundation, The Palast Investigative Fund, is offering the film, The Assassination of Hugo Chavez, as a free download here. Based on my several meetings with Chavez, his kidnappers and his would-be assassins, it was filmed for BBC Television. DVDs also available.]

Reverend Pat Robertson said,

Hugo Chavez thinks we’re trying to assassinate him. I think that we really ought to go ahead and do it.

It was 2005 and Robertson was channeling the frustration of George Bush’s State Department. Despite Bush’s providing intelligence, funds and even a note of congratulations to the crew who kidnapped Chavez (we’ll get there), Hugo remained in office, re-elected and wildly popular.

But why the Bush regime’s hate, hate, hate of the president of Venezuela?

Reverend Pat wasn’t coy about the answer: It’s the oil.

This is a dangerous enemy to our South controlling a huge pool of oil.

A really big pool of oil. Indeed, according to Guy Caruso, former chief of oil intelligence for the CIA, Venezuela holds a recoverable reserve of 1.36 trillion barrels, that is, a whole lot more than Saudi Arabia.

If we didn’t kill Chavez, we’d have to do an “Iraq” on his nation. So the Reverend suggests,

We don’t need another $200 billion war…. It’s a whole lot easier to have some of the covert operatives do the job and then get it over with.

Chavez himself told me he was stunned by Bush’s attacks: Chavez had been quite chummy with Bush Senior and with Bill Clinton.

So what happened to change Clinton’s hugs-and-kisses policy to Bush’s shoot-to-kill? Here’s the answer you won’t find in The New York Times:

Just after Bush’s inauguration in 2001, Chavez’s congress voted in a new “Law of Hydrocarbons.” Henceforward, Exxon, British Petroleum, Shell Oil and Chevron would get to keep 70 percent of the sales revenues from the crude they sucked out of Venezuela. Not bad, considering the price of oil was rising toward $100 a barrel.

But to the oil companies, which had bitch-slapped Venezuela’s prior government into giving them 84 percent of the sales price, a cut to 70 percent was “no bueno.” Worse, Venezuela had been charging a joke of a royalty – just 1 percent – on “heavy” crude from the Orinoco Basin. Chavez told Exxon and friends they’d now have to pay 16.6 percent.

Clearly, Chavez had to be taught a lesson about the etiquette of dealings with Big Oil.

On April 11, 2002, President Chavez was kidnapped at gunpoint and flown to an island prison in the Caribbean Sea. On April 12, Pedro Carmona, a business partner of the US oil companies and president of Fedecamaras, the nation’s chamber of commerce, declared himself President of Venezuela – giving a whole new meaning to the term, “corporate takeover.”

US Ambassador Charles Shapiro immediately rushed down from his hilltop embassy to have his picture taken grinning with the self-proclaimed “president” and the leaders of the coup d’état.

Bush’s White House spokesman admitted that Chavez was, “democratically elected,” but, he added, “Legitimacy is something that is conferred not by just the majority of voters.” I see.

With an armed and angry citizenry marching on the presidential palace in Caracas ready to string up the coup plotters, Carmona – the Pretend President from Exxon – returned his captive, Chavez, back to his desk within 48 hours. (How? Get The Assassination of Hugo Chavez, the film that expands on my reports for BBC Television. It’s free for the next few days here, thanks to the generosity of donors to our foundation.)

Chavez had provoked the coup not just by clawing back some of the bloated royalties of the oil companies. It’s what he did with that oil money that drove Venezuela’s 1% to violence.

In Caracas, I ran into the reporter for a TV station whose owner is generally credited with plotting the coup against the president. While doing a publicity photo shoot, leaning back against a tree, showing her wide-open legs nearly up to where they met, the reporter pointed down the hill to the “ranchos,” the slums above Caracas, where shacks, once made of cardboard and tin, where quickly transforming into homes of cinder blocks and cement.

“He [Chavez] gives them bread and bricks, so they vote for him, of course.” She was disgusted by “them,” the 80 percent of Venezuelans who are negro e indio (black and Indian) – and poor. Chavez, himself negro e indio, had, for the first time in Venezuela’s history, shifted the oil wealth from the privileged class that called themselves “Spanish,” to the dark-skinned masses.

While trolling around the poor housing blocks of Caracas, I ran into Arturo Quiran, a local merchant seaman, and no big fan of Chavez. But over a beer at his kitchen table, he told me,

Fifteen years ago under [then-President] Carlos Andrés Pérez, there was a lot of oil money in Venezuela. The ‘oil boom’ we called it. Here in Venezuela there was a lot of money, but we didn’t see it.

But then came Hugo Chavez and now the poor in his neighborhood, “get medical attention, free operations, x-rays, medicines; education also,” he said. “People who never knew how to write, now know how to sign their own papers.”

Chavez’s Robin Hood thing, shifting oil money from the rich to the poor, would have been grudgingly tolerated by the US. But Chavez, who told me, “We are no longer an oil colony,” went further – too much further, in the eyes of the American corporate elite.

Venezuela had landless citizens by the millions – and unused land by the millions of acres tied up, untilled, on which a tiny elite of plantation owners squatted. Chavez’s congress passed a law in 2001 requiring untilled land to be sold to the landless. It was a program long promised by Venezuela’s politicians at the urging of John F. Kennedy as part of his “Alliance for Progress.”

Plantation owner Heinz Corporation didn’t like that one bit. In retaliation, Heinz closed its ketchup plant in the state of Maturin and fired all the workers. Chavez seized the Heinz plant and put the workers back on the job. Chavez didn’t realize that he’d just squeezed the tomatoes of America’s powerful Heinz family and Mrs. Heinz’ husband, Sen. John Kerry (now, Obama’s nominee for US Secretary of State).

Or, knowing Chavez as I do, he didn’t give a damn.

Chavez could survive the ketchup coup, the Exxon “presidency,” even his taking back a piece of the windfall of oil company profits, but he dangerously tried the patience of America’s least-forgiving billionaires: the Koch Brothers.

How? Well, that’s another story for another day. [Watch this space. Or read about it in the book, Billionaires & Ballot Bandits.

Elected presidents who annoy Big Oil have ended up in exile – or coffins: Mossadegh of Iran after he nationalized BP’s fields (1953), Elchibey, president of Azerbaijan, after he refused demands of BP for his Caspian fields (1993), President Alfredo Palacio of Ecuador after he terminated Occidental’s drilling concession (2005).

“It’s a chess game, Mr. Palast,” Chavez told me. He was showing me a very long and very sharp sword once owned by Simon Bolivar, the Great Liberator. “And I am,” Chavez said, “a very good chess player.”

In the film The Seventh Seal, a medieval knight bets his life on a game of chess with the Grim Reaper. Death cheats, of course, and takes the knight. No mortal can indefinitely outplay Death who, this week, Chavez must know, will checkmate the new Bolivar of Venezuela.

But in one last move, the Bolivarian grandmaster plays a brilliant endgame, naming Vice-President Nicolas Maduro, as good and decent a man as they come, as heir to the fight for those in the “ranchos.” The 1% of Venezuela, planning on Chavez’s death to return them the power and riches they couldn’t win in an election, are livid with the choice of Maduro.

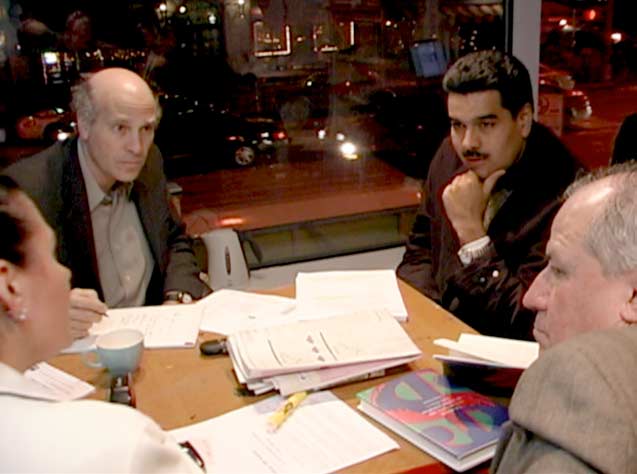

Chavez sent Maduro to meet me in my downtown New York office back in 2004. In our run-down detective digs on Second Avenue, Maduro and I traded information on assassination plots and oil policy.

Greg Palast (on left) and investigations team meets with Venezuelan Vice-President Nicolas Maduro (on right), New York, 2004. (Photo: Richard Rowley)

Greg Palast (on left) and investigations team meets with Venezuelan Vice-President Nicolas Maduro (on right), New York, 2004. (Photo: Richard Rowley)

Even then, Chavez was carefully preparing for the day when Venezuela’s negros e indios would lose their king – but still stay in the game.

Class war on a chessboard. Even in death, I wouldn’t bet against Hugo Chavez.

A terrifying moment. We appeal for your support.

In the last weeks, we have witnessed an authoritarian assault on communities in Minnesota and across the nation.

The need for truthful, grassroots reporting is urgent at this cataclysmic historical moment. Yet, Trump-aligned billionaires and other allies have taken over many legacy media outlets — the culmination of a decades-long campaign to place control of the narrative into the hands of the political right.

We refuse to let Trump’s blatant propaganda machine go unchecked. Untethered to corporate ownership or advertisers, Truthout remains fearless in our reporting and our determination to use journalism as a tool for justice.

But we need your help just to fund our basic expenses. Over 80 percent of Truthout’s funding comes from small individual donations from our community of readers, and over a third of our total budget is supported by recurring monthly donors.

Truthout’s fundraiser ends tonight! We have a goal to add 122 new monthly donors before midnight. Whether you can make a small monthly donation or a larger one-time gift, Truthout only works with your support.