Part of the Series

Progressive Picks

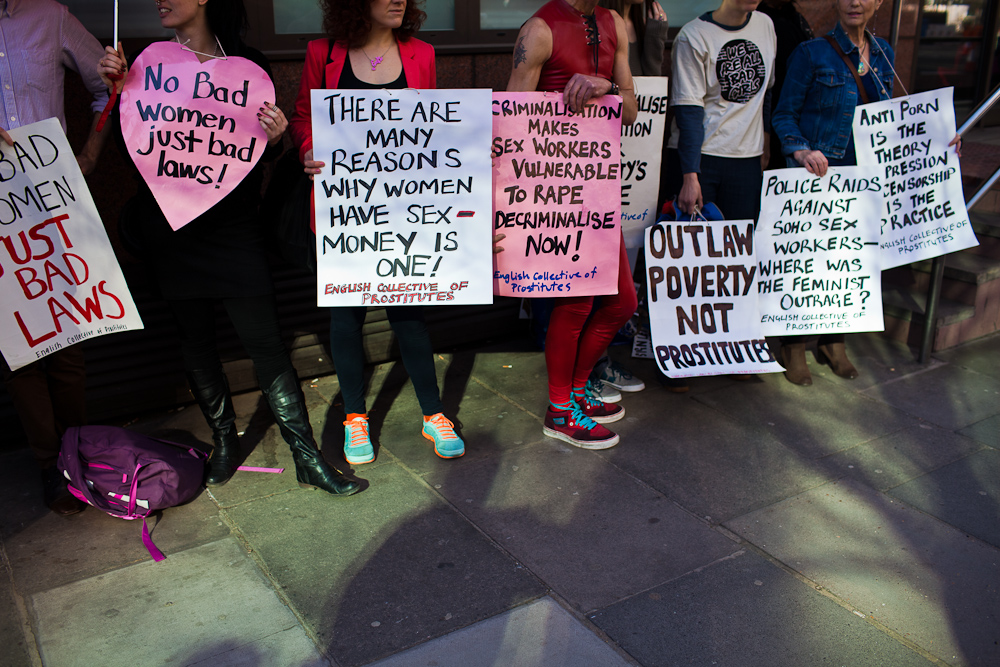

Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights takes a global view of commercial sex and the legal regimes that govern it. Authors Juno Mac and Molly Smith bring the reader through Britain’s messy Victorian prostitution laws, the U.S. prison-industrial complex, the false promise of “utopian” Scandinavia, and finally conclude with a critical look at decriminalized New Zealand. In this interview, they discuss policing, borders and work as they relate to sex work.

Samantha Borek: An entire chapter of Revolting Prostitutes: The Fight for Sex Workers’ Rights is dedicated to the “Nordic model,” and how Scandinavia is held up by many liberals and feminists as being a beacon of socialist values. In reality, this “utopia” is borne of a lot of puritanical, racist values. How can such a “socialist” region lack the resources to address sex workers in a meaningful way?

Juno Mac and Molly Smith: The answer is sort of in the question – it’s not about lack of resources, it’s about the desire to punish certain groups of people. The Nordic countries have the resources to help sex workers if they wanted to do so; the problem is that they don’t want to help people who sell sex. In the book, we quote a policy maker in Sweden agreeing that, “of course the law has negative consequences for women in prostitution but that’s also some of the effect that we want to achieve with the law.” The Norwegian government sent a fact-finding mission to Sweden in 2004, which resulted in a report into the effects of the Swedish approach to prostitution. The report that found “the law on the Purchase of Sex has made working as a prostitute harder and more dangerous” – but a few years after that report, Norway implemented the Swedish model anyway. So, it’s not a mistake or a lack of resources that the law produces these harms for people who sell sex – policy makers know about the harms of the law going in. The harms are, at the very least, part of the point.

There are a couple of different reasons for that desire to punish sex workers. The figure of the prostitute is an archetypally stigmatized figure: she provokes a profoundly misogynist disgust and anger, and those feelings of disgust and anger are intensified if she holds other stigmatized identities too – if she is a drug user, or trans, or a migrant or a person of color. You can feel that disgust and anger really clearly if you engage with carceral feminist spaces as a sex worker – in the book, we quote some examples of insults flung at sex workers on Mumsnet (which is the U.K.’s largest online parenting forum and also, sadly, a fulcrum of anti-trans hate). Mumsnet users are very [much] in favor of the Swedish model, and the women on the site would claim that that is in part because they care for women who sell sex and want to protect us from our “nasty” clients. However, even a cursory examination of the way sex workers are talked about on the site – all these incredibly vicious jibes that focus in really visceral ways on our bodies and bodily fluids, and this strong desire to punish sex workers through things like evictions – and you immediately see this ancient, libidinal, misogynist disgust jump out.

We think there’s also something in the way people are angry at homeless people. Visible homelessness makes people uncomfortable because it is such a sharp reminder of inequality and the way in which our society absolutely fails those at the bottom. Those feelings of uncomfortableness get paradoxically turned on the homeless person and become anger. Street-based sex work, in particular, brings out similar emotions for people – street sex workers are also often attacked by members of the public in ways similar to the ways homeless people are attacked. Scandinavia’s self-conception as having these very generous welfare states plays a part in that, too, because there’s almost this sense of, How dare these women still manage to be so poor that they have to do this – don’t they know this is Scandinavia?! It’s like, by continuing to need to sell sex, sex workers are seen as “ungrateful.”

The final really big reason that advocates of the Nordic model have this desire to punish sex workers is racism and white supremacy. Anti-prostitution policies are always anti-migrant policies, in part because migrants are disproportionately likely to do sex work, in part because racist policing means that anti-prostitution policy is invariably targeted most harshly at migrant workers and workers of color, and in part because migrant sex workers loom so large in racist imaginaries. White people really hate and fear the figure of the migrant sex worker, but in 2019, in progressive-ish circles, they mostly can’t just openly say that. So the Nordic model, which entails incredibly harsh policing targeted at migrant workers, becomes a way of scratching that itch while maintaining a veneer – potentially even to themselves – of progressivism. Amnesty International and others have found repeatedly that the Nordic model is used to target Black women for punishment, particularly through evictions, and, if their immigration status in any way allows it, deportation. This just doesn’t seem to register for Nordic model advocates – they can’t even bring themselves to say, “I like this law, but I agree these uses of it are bad.” People either outright defend these racist uses of the law, or they just treat it like they’ve not heard it. In the book, we quote policy makers talking about how any already flimsy sympathy for street-based sex workers in Norway totally evaporated when there was a perception that street-based workers had shifted to become mostly Black migrant women. So that was a key reason why, despite having a report by their own government that detailed how much the Swedish model harmed sex workers, Norwegian policy makers chose to implement that law: they wanted to harm and punish the Black sex workers that they believed were increasingly migrating to Norway.

It’s only apt to talk about the popular blogging platform Tumblr, which recently banned any graphic sexual content in a weak attempt at tackling the site’s rampant child pornography problem. How has this proved not only ineffectual, but also affected the sex worker community that used the site to do business? How has this affected their support networks?

Whether the demise of Tumblr porn has meaningfully tackled child abuse or just shifted it to more clandestine digital locations remains to be seen. The loss of Tumblr has certainly deeply impacted the sex workers who used it to sell their adult content, or as a low-cost alternative to having a professional website. A Tumblr profile could contain information about a sex worker’s availability, prices and agreed services. Thousands of sex workers also used Tumblr to find and connect with each other. Without this network, countless [sex workers] will have switched to soliciting business in vague code through dating apps and in public places. The same applies to Backpage, an ad site that was taken down a year ago and had a devastating effect on the sex worker community. These spaces — free and low-cost options for making money – are places the poorest sex workers were making use of, and without them they are at risk.

It’s also important to look on developments in censorship with a critical eye. The idea that platforms like Tumblr or Twitter censor content as some kind of digital social justice work for the good of women or children serves to deflect the reality that they are first and foremost businesses, with their hands tied by forces at play further up the stream. Tumblr wiped adult content in order to keep the app in the app store, capitulating to Apple — who in turn is responding to FOSTA-SESTA, a law that (among many other things) continues to prop up the war on sex trafficking and provides ever-increasing justifications for borders and policing. Images of child abuse online are a serious problem, but pushing all sexual content into the shadows simply increases undetectability – something that exacerbates danger, in varying ways, for both people selling sex and victims of abuse.

You open the book with three chapters simply titled, “Sex,” “Work” and “Borders.” How are these three subjects fundamental in understanding how sex workers navigate survival?

That’s a big question! We felt frustrated by the ways in which both the mainstream feminist movement and some strands of the sex worker rights movement talked about all three of these topics. When it comes to sex, it is obvious that prostitutes are stigmatized for having “the wrong kind of sex.” So sex workers react to discourses framing them and the sex they have as abject or disgusting by positing commercial sex as more like the kinds of sex the progressive parts of our society has mostly agreed to value – sex that has “real meaning” or “connection,” sex that centers “pleasure” for both parties, etc. The problem is, of course, that this pushes out the vast majority of sex workers, who don’t experience the sex they have at work as laden with meaningful connection. It pushes out more marginal workers, who have less control over their working conditions and thus the least ability to find “pleasure” there (and for whom the focus on pleasure, rather than economic security, access to housing, justice or health care is likely to miss the mark. If you’re worrying about imminent homelessness, deportation or drug withdrawal, then whether or not you orgasm at work is probably going to be irrelevant for you). Sex positivity has been a defensive attempt by sex workers to resist the ways in which we are often cast as “broken” or “damaged,” but we wanted to reach out to non-sex-working feminists and say that actually, for all of us, whether sex workers or not, sex as a woman (and/or queer person) within patriarchy is often a site of pain, ambivalence, trauma, and yes – sometimes damage. Sex workers shouldn’t have to feel that they have to frame the sex they have as meaningful, pleasurable or un-damaged to deserve rights and safety, not least because that’s an absolutely wild standard to apply to any sex happening within patriarchy. And that these difficult feelings about sex are one thing, but that shouldn’t distract us from the concerns of the sex worker worrying about homelessness, arrest, [substance] withdrawal or deportation.

Work is again a topic where our society has a bunch of contradictory ideas about what it is and what it means, and sex workers are right in the crosshairs of those contradictions. As with sex positivity, sex workers often feel pressured to liken their work to other kinds of work that our society values, in an attempt to not only be seen as workers but to be seen as valued workers. We empathize with that impulse, but again, we worry that it leaves behind the most marginal, who are least able to reframe their work a vocational calling, or “like” work that’s seen as more legitimate. Conversely, as we discuss in the book, carceral feminists often argue that sex work can’t be work precisely because sex work is bad work: unenjoyable, exploitative, etc. To argue that something is not work because it is unenjoyable or exploitative is, of course, to exclude the vast majority of the world’s workers from the category of worker. Such a position paradoxically argues that it is only workers who are already having a great time at work who deserve labor rights. Instead of saying sex workers deserve rights because it is good work, or that sex workers do not deserve rights because it is bad work, we argue that it is because sex work is bad work that sex workers need rights. We want to acknowledge the ways in which sex work, like a lot of work, is pretty shit – not so we can all just wallow in how bad everything is, but because that’s a solid base for organizing together, as workers, to resist and transform the conditions in which we work.

As for the topic of borders, we were struck by how strangely absent borders and immigration enforcement were in most mainstream feminist conversations about the sex industry. Or even sometimes seen in a positive light. We argue that it is closed borders and immigration enforcement that is the factor in making people who migrate vulnerable to the kinds of exploitation or harm referred to when people talk about trafficking. And yet immigration enforcement is presented by the state as part of the solution to trafficking – when, in fact, it is the cause. Sometimes sex workers try to “push away” the topic of trafficking by saying something like, “That’s totally different from sex work.” To us, that feels inadequate because it abandons people who are experiencing harm – it says, they’re nothing to do with us. We want sex workers to be more confident in saying that actually, people are experiencing harm as a result of the criminalization of migration, and it should be obvious that more criminalization – whether of migration or prostitution – isn’t going to fix that. Everybody deserves the right to migrate if they want to, and to work with access to labor laws and justice wherever they are living. Migrant rights and sex worker rights are inseparable.

How has criminalization, whether of buyers or sellers of sex, made sex workers more vulnerable to violence and economic instability?

In the book we try to very clearly break down the specifics of how criminalization impacts people selling sex; we strongly believe that if policy makers and the public can identify with the rational decision making that sex workers do when trying to survive, they will easily be able to understand how dangerous criminalization can be. For many, it may seem relatively obvious that arresting sex workers and putting them in prison is bad for their health and human rights, but we nonetheless take a chapter to drive home the lesser discussed aspects of police violence, prisons and criminal records. These things — and the grave consequences they have for people selling sex — should not be taken for granted.

However, we are particularly at pains to help people understand how the criminalization of third parties like clients and bosses is also very dangerous. To some, it may seem almost intuitively correct that criminalizing a client or a pimp would make him less powerful and therefore give a sex worker more power, but if you think like a sex worker, the problems with this come into focus.

If you are a sex worker and need to see, say, four clients in one evening to cover the costs of rent, drugs, food and condoms, then a law that cuts the [number] of clients in the street by half will force you to reckon with homelessness, withdrawal, hunger and exposure to STDs. Sex workers in Sweden and Norway have to spend longer in the streets to earn enough, and have to protect their clients from police detection by soliciting in more isolated areas. When researchers asked people in Vancouver, Canada, how criminalization of clients had affected them, one street-based sex worker said, “While they’re going around chasing johns away from pulling up beside you, I have to stay out for longer…. Whereas if we weren’t harassed, we would be able to be more choosy as to where we get in, who we get in with, you know what I mean? Because of being so cold and being harassed I got into a car where I normally wouldn’t have.”

Negotiations on the street are rushed to satisfy the client’s anxieties about being caught, and the heightened risk of him nervously aborting the idea and dashing away weakens the sex worker’s ability to negotiate higher rates. She may agree to be driven further out of the way in the client’s car to ease his worries, which exposes her to a deeper risk of violence. Clients who book sex workers online are able to insist on being anonymous, and sex workers are forced to acquiesce for the sake of making the money they need. These effects are some of many, many ways in which sex workers around the world pay the price for trying to survive, under legal regimes often designed for their supposed protection.

How has the term “sex trafficking” been co-opted by drafters of legislation (such as SESTA-FOSTA) — and even some feminists — to harm sex workers?

It hasn’t really been co-opted – the mainstream meaning of sex trafficking has always been about white reaction. The “white slavery” panic of the late 19th century was semi-sublimated white racist anxieties about the aftermath of chattel slavery: The idea of “white slavery” allowed white people to imagine themselves victims; their rosy-cheeked daughters stolen by men of color in rapidly growing cities. In the book, we quote 19th century writers saying that “white slavery” was “worse” than chattel slavery – and we also quote people in the current moment saying that modern trafficking is worse than the Atlantic slave trade. Black suffering is evoked only to be used as a scene-setter, and white people are able to assuage guilt over historical and contemporary racial injustice by positing themselves as victims. It is extremely common to see modern anti-trafficking materials feature photographs of a dark male hand over a white woman’s mouth, for example. The effect, both in the 19th century and today is criminalization that actively targets Black people and other people of color – the 1905 Mann Act, which was one of the first “anti-trafficking” laws passed in the U.S., effectively criminalized Black men in relationships with white women. Boxer Jack Johnson was prosecuted under the Mann Act for a relationship with a white woman.

Modern anti-trafficking law targets male migrants for criminalization or deportation as “traffickers,” and female migrants for criminalization or deportation as “victims of trafficking.” President Trump loves the titillating imagery of the anti-trafficking movement, and that’s because he accurately recognizes it as a white nationalist tableau. Anti-trafficking law can be used to put ever-increasing numbers of Black and Brown people into prison or into immigration detention facilities. In Europe, refusing to rescue drowning migrants in the Mediterranean is presented by E.U. leaders as a just response because the sinking boats are seen as belonging to “traffickers.” As a result, the Mediterranean Sea is one of the most deadly borders in the world. Those dying there are people of color from the global South who have an absolute moral claim on Europe – for centuries of European colonialism and resource extraction, for war and for climate change. Yet through the frame of “trafficking,” it is seen as reasonable to allow thousands of people to drown every year. In the U.K., the government relatively frequently sends out letters agreeing that someone is a victim of trafficking with a letter telling them they are about to be deported. Anti-trafficking policing is anti-migrant policing – increasingly militarized borders and deportation are central to the state’s response to situations it deems trafficking.

Are we even close to a form of decriminalization of sex work? What would that mean to sex workers as a whole? What does it look like?

Whilst decriminalization is the shared goal of the whole sex worker rights movement, the only two existing examples of decriminalized sex work take place in New Zealand and New South Wales, Australia. In these jurisdictions, people can sell sex with friends from a shared flat as an informal co-operative without risk of arrest. Both indoor and outdoor workers can speak clearly with clients about services, condom use and prices, without having to rush or use euphemisms. Reporting a manager will not get the entire workplace shut down by police, but managers are held accountable under labor law. Some examples of the labor rights New Zealand’s sex workers can expect include protection from sexual harassment at work, proper breaks on shifts and between shifts, safer sex materials and the power to insist on them, provisions stopping workplace discrimination, and the right to refuse customers.

In New Zealand, street-based sex workers can work with groups of friends in safe public places, without fear that the police will come to disrupt them. Sex worker Claire says that prior to decriminalization, “We were in the darkest places … just real shady,” compared with post-decriminalization, where “it changed … a lot of us had to hide before then.” Incredibly high numbers of street sex workers (over 90 percent) feel they have employment rights and legal rights; numbers that would hold up well in comparison even to formal economy work in bars and call centers.

While this framework has won praise from Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, UNAIDS and the World Health Organization, it is of course far from perfect. Many marginalized sex workers are left behind by elements of criminalization (such as the criminalization of drugs, migration and migrant sex work) that remain. The Global Alliance Against Traffic in Women called the New Zealand model “a starting point,” and so that’s what we set out to examine in the book: How can we learn from what’s working in New Zealand, as well as learning from what isn’t?

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.