Part of the Series

The Road to Abolition

Something has come unstuck. The common sense about policing has abruptly changed.

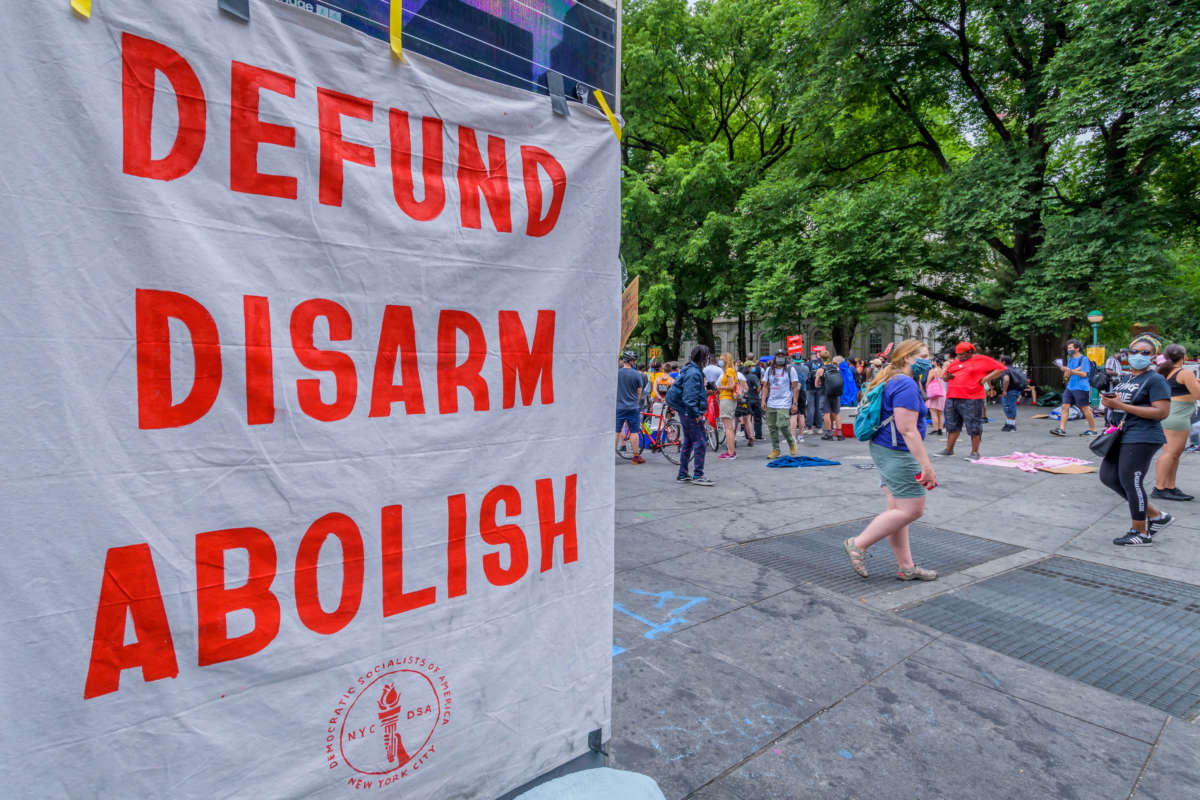

This shift was a long time coming: Prison abolitionists — a movement of scholars and activists, notably spearheaded by Black women such as Angela Davis and Ruth Wilson Gilmore — have spent decades organizing toward a goal of abolishing the prison system. The Black Lives Matter movement and a new generation of Black-led organizing have kindled a new moment in which a world without police feels truly possible.

After decades of expanding police power — bolstered by a hegemonic “law and order” discourse and a bipartisan “tough on crime” agenda — something snapped when Minneapolis police were filmed callously suffocating George Floyd, an unarmed Black man. Suddenly once-staunch defenders of the police — even their own unions — are calling for reform, and moderates advocate defunding specific programs or entire departments. The police have come to be seen as a threat to public safety rather than its instrument, and the ideological framing of “Black criminality” has given way, at least for the moment, to that of institutional racism. More than two-thirds of Americans (69 percent) believe that Floyd’s death is “a sign of broader problems in [the] treatment of black Americans by police,” and 81 percent believe “police in America need to continue making changes to treat blacks equally to whites.” As recently as 2014, it was a minority (43 percent) who saw similar incidents as “a sign of broader problems.”

As cities burned and crowds fought with cops, surveys showed that three-quarters of Americans (78 percent) saw the anger driving the uprisings as at least partially justified, and a majority (54 percent) felt similarly about the protesters’ militant tactics, including the burning of Minneapolis’s Third Precinct station house. Twice as many people — including a majority of whites — report being concerned about police violence as express concern over protester violence. A large majority (74 percent) express support for the protests (47 percent “strongly support” them).

Riots get results. The cops who killed George Floyd are being prosecuted; many departments are banning chokeholds; and police chiefs, district attorneys and other law enforcement leaders have resigned, one after another, across the country. Police budgets are being slashed, with the funds reallocated to social spending — reversing the trajectory of the last half-century. The Minneapolis City Council voted to disband its police force altogether and try something else instead.

Some of the concessions responded to long-standing complaints, and others represent changes that no one had even demanded: Lego is de-emphasizing police-themed toys. Babynames.com featured a stark black banner on its front page listing dozens of victims of racist violence, beginning with Emmett Till, and reminding us that, “Each one of these names was somebody’s baby.” The long-running television program “Cops” was abruptly cancelled. Corporations started pouring money into civil rights organizations, and celebrities publicly challenged each other to bail out arrested protesters.

Twenty years ago, I began work on a history of policing in the United States, which appeared in 2004 under the title Our Enemies in Blue. (It is now in its third edition.) The main argument of the book is that the core function of the police is not to fight crime, to protect life and property, or even to enforce the law, but instead to preserve existing social inequalities, especially those based on race and class. In making that case, I looked at the origins and development of the institution, the centrality of violence in police work, and the persistent bias in the law and its enforcement. I also forwarded a number of contentious (and at the time, almost heretical) claims: that modern policing originated not in the New England town watch, but in the Southern slave patrols — militia groups responsible for enforcing pass laws and preventing uprisings; that cops are not workers and police unions are not labor unions; that community policing is not a program for progress but a counterinsurgency strategy; and that the institution of policing must be abolished rather than reformed. At the time, none of those were accepted positions, even among many strident critics of the police. They remain today minority views, but it has become a substantial minority. These points have entered the mainstream discourse: Historians increasingly acknowledge the significance of slave patrols. Unions are calling into question the legitimacy of police unions, and even breaking ties with them. The military literature has become increasingly explicit in comparing community policing with counterinsurgency. And even mainstream politicians find themselves debating the question, not merely of reforming the police department, but of defunding or disbanding it.

Meanwhile, the agenda of activists has quickly expanded beyond policing: Around the world, crowds pulled down statues of Confederate generals and slave owners. Popular Mechanics ran articles offering practical advice on avoiding police surveillance at protests, and a how-to guide to pulling down racist statues. NASCAR barred displays of the Confederate battle flag, and Mississippi decided to remove the Stars and Bars from its state flag. A street adjacent to the White House has been renamed “Black Lives Matter Plaza.” Employers adopted Juneteenth as a paid holiday. And Johnson and Johnson announced a new line of darker Band-Aids.

Many of these gestures are purely symbolic. But while some changes may not do much, that is not to say that symbolic gestures are meaningless: the symbolism itself demonstrates something of the emerging consensus.

In addition to being a pivotal moment for organizers, this shift in public consciousness would seem to recommend an expanded agenda for researchers. Most crucially, we should find ways to put our work in the service of social movements, always remembering that it is the movement, and not the scholarship, that propels change.

We should, of course, continue to document the prevalence of police violence, analyze its causes and evaluate proposed reforms. But in the present crisis, provisional answers are already available and widely circulating. What is more urgently needed is further work documenting and evaluating alternatives to policing, identifying best practices and organizational features that correlate with good outcomes.

Furthermore, we must work to situate abolition as part of a revolutionary program, to make clear the limits of defunding (or even disbanding) the police, and to make the argument that abolition cannot end with policing, but must extend to the entire criminal legal apparatus — the machinery of prosecutions and punishment, even probation and “community-based” corrections. We must not be afraid to embrace the radicalism of such proposals. Just as we highlight the structural role the police play in economic exploitation and racial oppression, we must articulate the importance of abolition in the broader revolutionary project of overthrowing white supremacy and capitalism.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.