Artists, activists, and neighbors convened in Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital, this August to paint a mural of their fears, pains, and hopes over the past year, since uprisings in July 2024 reshaped Bangladeshi politics and life. Their experience offers important lessons for other anti-fascist activists who seek to emulate the successes, and avoid the pitfalls, of Bangladesh’s revolutionaries.

During 2024’s “Bloody July,” hundreds of thousands of Bangladeshis rose up against corruption, class stratification, nepotism, and exploitation under former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and her party, the Awami League. Protests began on June 5, 2024, with small student demonstrations against preferential access to civil service jobs at a time when 30 percent of young people who aren’t students or in job training programs are unemployed. Protests grew throughout July and August, incorporating the working and middle class.

The state responded with violence. Thousands were injured and hundreds were killed. This was not new: Hasina’s government covered up the 2013 Shapla Chattar (Water Lily) Massacre of opposition activists, and had disappeared untold numbers of dissenters in the Aynaghor, the Awami League’s secret prisons and torture centers, for years. Hasina called 2024’s student protesters “razakars” (traitors to the state) to justify her reprisals.

The state’s violence emboldened resistance. Activists mobilized 214,000 protesters to face arrest, and hundreds of thousands more onto the streets, in a popular movement to overturn the dictatorship. Hasina fled the country and the dictatorship fell on August 5, 2024.

Since that time, Bangladesh has been in flux. The dictatorship’s fall created a power vacuum and right-wing forces have expanded. The diminishing hope has been compounded by low public political alignment, economic and political disarray, and student activists still finding their footing. A caretaker government, led by Nobel Peace Prize winner Muhammad Yunus, was appointed with little democratic mandate, and is under attack from the Bangladesh Nationalist Party. The Awami League has been banned from elections called for February 2026, fanning fears of a new dictatorship, just with a different leading party.

One Year Out: Complications and Activist Reflections

Since 2024’s Bloody July, attacks on Adivasi (Indigenous) communities, women, trans and queer people, and religious minorities have been numerous. Hope after the uprisings has given way to despair and fear of a future resembling the past.

In August 2025, as the one-year anniversary of the uprisings approached, commemorative events spread across Dhaka. I attended one with Tasaffy Hossain, a feminist activist and the founder of feminist organization Bonhishikha. Over the past year, Bonhishikha facilitators convened activists struggling to make sense of the trauma and ambivalence of the past year.

Hossain told me that the commemorative event organized by the government of Bangladesh felt “removed from the reality” of what August 5 really felt like — a day of “anxiety, pain, and immense loss” coexisting with “an immeasurable sense of achievement and exuberance on the streets.” The government-organized event focused on celebration “instead of reflection, rebuilding and reforming what had been lost,” she added.

But Hossain still finds hope in the grassroots, saying, “Part of me is just neverendingly optimistic, and part of me enjoys feeling that something somewhere can still shift, and I get to make it happen.”

Hossain’s hope, in the face of loss and pain, is something that I saw repeatedly over the past year — and something that should resonate with anti-fascists everywhere.

Political Hope and Feminist Resistance in Arts and Culture

Arts and cultural events have maintained key streams of hope for new feminist and anti-fascist futures. Tarannum Nibir Ali, an artist, activist, and fashion designer, spoke to me about doing this through their fashion label, Urukku. At a recent show, models held posters that emphasized the need for sustainable fashion to push back against ecological collapse. One read, “The dignity of workers is the dignity of the nation” — marking a firm commitment to worker justice in a country still recovering from the deadly Rana Plaza garment factory collapse.

At the event, Ali walked down the runway with Urukku’s master tailor, Habib Bhai — an unconventional choice for a fashion show. Ali told me, “The core person of the team is the artisan, who is Habib Bhai, the master tailor. I think our industry should also focus on the artisans, not just the designers.”

Ali also lives this commitment through their direct action and activist work. Alongside their collaborative partner Manzoor Real, they hosted a recent gallery opening where artists displayed work made from cardboard boxes, plastic containers, scrap metal, and fabric scraps — all salvaged from Dhaka’s ever-expanding trash-scape. The opening invited viewers to “reimagine waste,” as a large sewn banner proclaimed, and pieces proclaimed solidarity with Palestine and hopes for a brighter future. The opening concluded with a jam session, where participants played homemade rain sticks and didgeridoos and sang about their hopes for freedom in a country where those hopes sometimes feel far away.

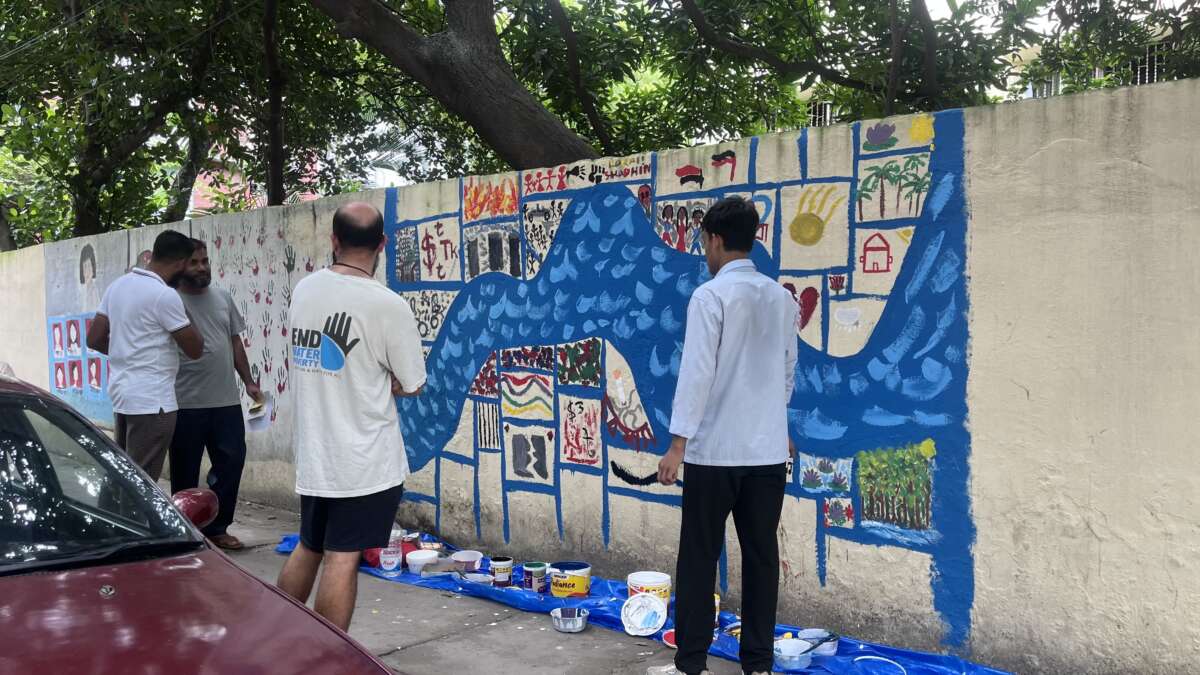

Even as right-wing forces attack their work, artists persist in the rich Bangladeshi tradition of resistance-oriented popular arts and music. Members of a theater company with whom I briefly worked to score a theatrical production told me about theater events getting attacked and shut down by Islamic right-wing factions that believe performance to be haram, or religiously forbidden. Musicians and DJs from local collectives with whom I collaborated faced repeated event postponements and cancellations. But artists, activists, and neighbors still find hope, as I saw in the muraling workshop.

Ayela Amin, an artist, DJ, and fashion designer who painted murals with us, had faced a brutal assault this year at a local tea shop, where a group of men attacked her and a friend, purportedly for smoking in public and not following their patriarchal interpretation of Muslim female propriety. When she approached the police, they shamed the two young women further. In response, Amin made art and music, and deepened her feminist activism over the past year, including participating in a shutdown of the street outside Parliament, and in a larger feminist march called the Moitree Jatra.

Reflecting on this while painting our mural, Amin told me, “I rarely stop to think of what I do as ‘activism.’ It has never felt like a choice. I’ve only ever experienced life in a way that makes this work necessary: speaking up, showing up, and creating.”

When asked about her direct-action experience, Amin said, “The protest outside Parliament was especially powerful for me, because it happened right after my assault. Even though the protest was about all violence endured by marginalized groups in Bangladesh, I felt seen in that moment. It reminded me that I have people around me who care, who believe in justice, and who will stand with me.”

Amin spoke of the importance of feeling seen in movements, and of building movement spaces where we can show up as our most rageful, but also hopeful and creative selves.

For an example of this combination, she turned to the feminist march. “The Moitree Jatra was an unforgettable moment of solidarity,” Amin told me. “Since the revolution, the political climate has been more chaotic and the streets less safe. I’ve found myself staying home more often. But that solitude has given me more space to create through fashion and music. I think of these as extensions of my activism too: culture work that resists erasure and asserts that we are here, we exist, and we have something to say. That gives me hope. That I can keep carving out small pockets of freedom and truth, even in hostile times.”

Amin’s words about the importance of feminist culture work toward change align with the statements of women activists who participated in the uprisings. These activists have found space for feminist formation and for a belief that the country can become better, even in the face of further isolation and patriarchal control.

Worker Justice and Mass Organizing for Labor Rights and Against Fascism

Workers organizing for justice also shared lessons about finding hope in the face of state power during what seemed to be an opening for labor organizing after the Hasina years, but often wasn’t.

Garment worker organizing has been a key space of resistance in Bangladesh. The nation has the world’s second-largest garment industry, and the devastating 2013 Rana Plaza collapse is only one example of the horror that largely poor women workers face daily. Kalpona Akter is the founder and executive director of the Bangladesh Center for Workers Solidarity, and founder and organizer with the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation. “The fashion industry, and all industries, need to be following the people who make the industry run — the workers,” Akter said, “It’s critical that spaces are centering garment workers’ demands about just pay and safe working conditions when thinking about democratizing — in fashion or elsewhere.”

During Hasina’s rule, Akter and others experienced extensive targeting for their organizing. But the fall of the dictatorship brought mass economic turbulence, complicating the fight for worker justice. The same was true for fashion models. One, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of targeting, told me, “‘Democratizing fashion’ is a very unique concept, and I support the vision,” but questioned the industry’s labor standards, explaining that even the most supportive spaces “weren’t very transparent,” “played a very dirty game” about compensation, and “need to be more professional in terms of payments and communications, and more conscious about security.”

Imran Jamal, an activist and a researcher with development NGOs, echoed this:

The uprising has overlooked the working class. One of the caretaker government’s first actions was to violently quell protesting garment workers at a factory outside Dhaka. We have seen a similar lack of changes for delivery workers with whom we research. One year later, the industry is still completely unregulated, and workers face continually precarious labor conditions in a volatile economic market.

A forthcoming report from the BRAC Institute for Governance and Development that Jamal shared with me confirms Jamal’s sentiments about the lack of worker justice, even since the uprisings.

Hope at the Center: Student Activism and Youth Futures

Like feminist and worker activists, student protesters rose up in July 2024 — many of them spurred to action by the feeling that they had no future in Bangladesh. Under Hasina, the elite were getting richer. Hasina’s family and cronies extracted millions from Bangladeshi citizens into private companies and lavish homes. Meanwhile, the poor were getting poorer. A dispute over access to civil service jobs was the uprising’s trigger because these jobs were a rare pathway to stability for young people, thwarted through autocratic nepotism. This was felt across groups and classes.

But the past year hasn’t brought all that was hoped for. The caretaker government has been notoriously opaque, rarely sharing with or consulting the public. And while some of the uprising’s student leaders have taken on governmental roles, many have felt left in the dark.

I spoke about this with Muntasir Rahman, a queer activist and student leader within the emerging formal student political party, NCP (National Citizens Party). Amid a flurry of student, government, legal, media, and queer activist meetings, Rahman told me, “The student leaders were scared for their lives, but they were brave enough to come forward. I saw that they were untamable, not afraid to do the right thing. That’s why I stood up: to stop the bloodshed and Hasina’s killings of innocents, and to protect the student leadership.”

Rahman has spent the past year building out the student party’s ability to contest in the upcoming elections, and he was named a member of the NCP’s formal leadership. But Rahman has also been involved in queer organizing and human rights work for years. When the media and right-wing forces got wind of Rahman’s involvement in queer activism, his identity became a national media story. Anti-queer attacks against Rahman dominated press coverage of the NCP for days.

Speaking to this fallout, Rahman said, “The students knew about my identity as a queer person and activist, and they were very respectful; they didn’t have an issue. But because of public pressure, they couldn’t take my side in the media.”

While others might have taken this as a betrayal, Rahman again found hope in the face of despair. “I have gone through my own coming-out phase, and I have seen how my family and friends reacted back then,” Rahman told me. “I know how people can make mistakes in that moment.”

Connecting to his ongoing commitment to the NCP, he said, “It’s important for Bangladesh to have a balance of power in Parliament to go in the right direction. The current interim government is not well equipped to resist the rise of right-wing forces. So that’s why I do the work I do. And I believe the student and revolutionary parties have the best shot.”

I was surprised to hear Rahman’s hope, especially after he noted the assassinations of Xulhaz Mannan and Mahbub Rabbi Tonoy, queer activists who were brutally murdered by right-wing vigilantes in Mannan’s home in 2016. But, Rahman said, “It’s better to take a constructive and principled stand, not to burn bridges. The political parties aren’t going anywhere. So, I’m hopeful. We have a chance to establish a democracy. That’s the point of hope.”

Rahman’s words and actions moved me — and echoed what I see across Bangladesh. Amid worsening conditions, oppressed communities have continued to organize. Adivasi activists have mounted protest after protest in the face of increased settler violence. Artists continue to make art; musicians continue to perform their music. Queer and trans people continue to dance and DJ and fight for their rights. During the mural workshop, numerous passersby stopped to watch, join in, and share their hopes for the future. One middle-aged woman passing by spoke at length with Amin about her fears and heartbreak, but also about her hopes for a stronger and more democratic Bangladesh. Even amid great pain, worsening economic conditions, and a crisis of faith about the future, activists and culture workers persist.

This hope resonates with the hope of anti-fascists across the globe: Through varied organizing and big-tent coalitions, keen eyes to long-term strategy, and never neglecting connection and fun, we, too, can persist.

I reflected on this with Ruhul Abdin, a British Bangladeshi artist and queer activist who has lived in Dhaka for a decade. Abdin spoke about Sahara Choudhury, a trans student activist fighting expulsion from university and a potential terrorism charge. Choudhury has also been active around agitating for gay marriage rights and challenging Article 377, a British colonial-era law that criminalizes homosexuality in Bangladesh. Choudhury’s cartoons about her transphobic university professors were reported as a threat. This story sounded like another tale of theo-fascist woe, but Abdin saw it differently.

“We had our days, and many of us are traumatized after Xulhaz,” Abdin said. ”But these young trans and queer activists, they have fire. They’ve seen that they can topple a dictatorship. So why can’t they overturn Article 377 and get rights for gay people? Why not enshrine better protections for trans people? They believe they can, so they’ll do the work.”

The murals painted by students across the country in July and August 2024 say the same. They proclaimed that Gen Z would take no bullshit, that they would clean up the mess of the generations prior to them, that the Z stood for zero tolerance for dictatorship and zero fear.

And so, one year later, even amid all the pitfalls of the past year and terror about what’s to come — probable unrest leading up to February’s elections, potential further right-wing shifts or another party’s dictatorship — these activists and artists choose hope in the face of uncertainty and despair. They, like revolutionaries around the world, believe that life and politics can be better. And through working toward that, through art and organizing and community, they insist on hope.

Our most important fundraising appeal of the year

December is the most critical time of year for Truthout, because our nonprofit news is funded almost entirely by individual donations from readers like you. So before you navigate away, we ask that you take just a second to support Truthout with a tax-deductible donation.

This year is a little different. We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. 2025 was a year of frightening censorship, news industry corporate consolidation, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We’ve set an ambitious target for our year-end campaign — a goal of $250,000 to keep up our fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout before December 31. If you have the means, please dig deep.