Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

There is a phrase used again and again when people bring up something uncomfortable about the environmental movement. We are told that we are being “divisive.” The people who make themselves vulnerable by vocalizing their concerns, or worse–their dissent, are vilified and told they are “fracturing” the movement. Why is pointing out where there’s room for growth so threatening? But more importantly: can you fracture something that was broken to begin with?

On January 25th, thousands of people gathered at the Utah State Capitol to protest the state’s horrible air quality. On the surface, this event was a great success. The turnout was amazing, with the front grounds of the capital flooded with people. Behind the scenes, something was happening that needs to be addressed: the lack of frontline voices, specifically those most impacted by multiple oil refineries in the Wasatch Front.

Peaceful Uprising threw our support behind the Clean Air, No Excuses rally, because air quality in the Salt Lake valley is the worst in the nation, and has at times this year surpassed pollution in Beijing. We supported the rally because in our work to stop tar sands and oil shale mining, we are demanding that Tesoro and Chevron stop their current refining of Canadian tar sands, and that Salt Lake pass a moratorium on all tar sands refining in the future. Salt Lake’s oil refineries and industry polluters must be held accountable, and stopped, if clean air is to be attained. Most importantly, however, we supported the rally because frontline communities, those marginalized and neglected folks so often made invisible, are disproportionately impacted by pollution and extraction. It appeared that the clean air movement in Utah was just that–a movement, and a movement that invited, supported, and included the voices of all those involved and affected.

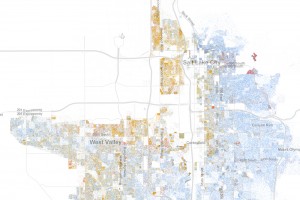

Salt Lake City as depicted on Dustin Cable’s map, drawn on data from the 2010 U.S. Census (showing one dot per person, color-coded by race; blue = white; orange = Latino).

Salt Lake City as depicted on Dustin Cable’s map, drawn on data from the 2010 U.S. Census (showing one dot per person, color-coded by race; blue = white; orange = Latino).Two days before the rally, we learned the line-up of speakers did not include any voices that represented the refinery neighborhoods, and not one person of color. Salt Lake City is a place divided, racially and economically. On the east side of the city, the population is predominantly white; on the west side, predominantly people of color. It also happens that Tesoro, Chevron and Big West Oil refineries are located on the west side. That a rally called to demand clean air would not include one voice from these communities is not only unthinkable, but neglectful.

Organizers from the rally were contacted multiple times in the days leading up to the event. Rebecca Hall, an African-American scholar who has written prolifically on issues of climate justice, environmental racism, and frontline communities, and works in Rose Park, offered to speak on these issues and relate them back to Utah’s clean air issue by talking about tar sands and the refineries. We asked also that someone living in the refinery neighborhoods be allowed to speak about their experience (and offered to help organizers to line up such a person). Alternatively, we asked that the rally organizers make mention at the event about this oversight, and that they publicly voice their desire to include the voices of the front lines moving forward. These resolutions were declined.

Instead, we had some very troubling conversations. We were told race had nothing to do with clean air in Utah, and were asked to supply “proof” that the neighborhoods surrounding the refineries were disproportionately affected. Requiring communities of color to “prove” that they are being poisoned more than the rest of the population before including them in the rally is unacceptable. What gives the owner of Lewis Stages, a private bus company, more authority than a family living next to the refinery to speak about clean air, and why was he not only invited to speak, but courted? Are celebrity and social capital more important than lived experience?

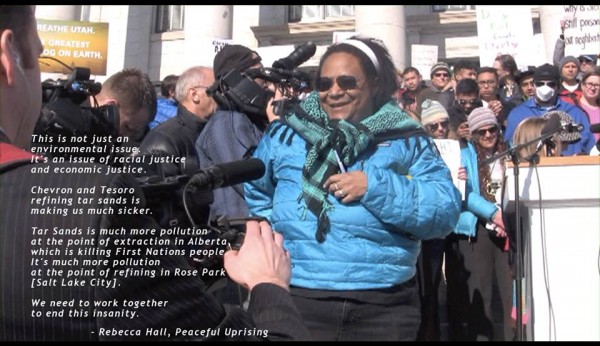

Rebecca Hall immediately after speaking at the Clean Air, No Excuses rally (Photo: Peaceful Uprising)

Rebecca Hall immediately after speaking at the Clean Air, No Excuses rally (Photo: Peaceful Uprising)Event organizers decided at the last minute to add “diverse” voices, represented, for the most part, by individuals from the LGBTQ community. These speakers were invited under the condition that they only read the white organizers pre-made material. Practices such as these do not build an inclusive movement, but result in the tokenizing of individuals and communities that should instead be at the forefront of our organizing. Inviting people to participate, but not contribute, and instead using them as proof of inclusivity, is incredibly harmful; not only is it offensive and isolating to the people involved, but it continues to hide that the voices of these very people are absent from the narrative to begin with.

Reaching for whatever diversity event organizers could find behind the podium during the event, Rebecca was “allowed” to approach the podium if she could promise not to “disrupt” the rally, and told to only read text that was being pointed to by a white organizer on a sheet of paper. A woman yielded her speaking time to Rebecca, who spoke briefly. Rebecca’s intent was never to disrupt the rally, but instead to provide an important addition to the narrative being created that day.

The questions we keep asking are, “Is clean air for all lungs, or only for the lungs of the privileged? Is a life free from pollution and extraction something we all deserve, or is that a right reserved only for white communities?”

As a white person in this world, you are either complicit in, and benefiting from, systemic racism/white supremacy, or you are actively, overtly and explicitly pushing back against a system that fosters racism while acknowledging the privilege you can’t help but receive. When we talk about race, and racist behaviors, there is often a knee-jerk response: “But I’m not racist!” And while an individual may not have intentionally engaged in racist behaviors, wounds caused unintentionally are still wounds. When the race you were born into has all the institutional power, social capital, credibility, and resources, you benefit whether you are aware of it or not. Put another way: when the rules are set up to benefit you, they are stacked against someone else, whether you are aware of their experience or not. The question is: When inequity is made known to you, how will you react?

Though some mainly white communities, like the one by the Stericycle medical waste incinerator, are affected seriously by pollution—especially if they are low-income—environmental hazards disproportionately impact communities of color. This is what we mean when we talk about environmental racism, something that even the EPA regards as a serious issue. Communities of color are more likely to live beside sources of pollution, like refineries and mines. Utah Physicians for a Healthy Environment state that the air inside homes by refineries like Tesoro is more toxic than the air outside, since emissions accumulate there over time. These communities have a large percentage of non-white residents. Likewise, people of color have less access to housing, fair wages, and health care than white people, making them often less equipped to cope with severe pollution.

Communities everywhere are experiencing the deadly effects of fossil fuel refining. In Manchester (Houston, TX), Richmond, CA, Detroit, MI, and elsewhere, neighborhoods are being treated as sacrifice zones, given over to the fossil fuel industry, and the residents made invisible. The same holds true for communities on the frontlines of extraction.

Diné gathering in the Four Corners area (photos courtesy of Reclaim Turtle Island)

Diné gathering in the Four Corners area (photos courtesy of Reclaim Turtle Island)

The same weekend of the clean air rally, members of Peaceful Uprising were working with communities living on the Diné Reservation, visiting uranium mines and other extraction sites in the area, and helping plan for a spring gathering. Others are waiting for Obama to make his final decision on the northern leg of the Keystone XL pipeline (as the southern leg is already in the ground), and will journey to Lakota territory to stand with them as they fight to protect sacred sites. Taking the lead from, and physically standing with, frontline communities is not only important to our work, it is necessary if we have any hope of succeeding.

Peaceful Uprising’s efforts toward Climate Justice are a work in progress. We make mistakes–many of us have white and class privilege and are often confronted with the blind spots these privileges create or enable. We are learning through trying, sometimes failing, and constantly trying to do better. As the Zapatistas say, “Caminamos preguntando”: “We are asking while we walk”. But we want to build communities where these mistakes and blind spots are addressed–not next year, not next action, but as soon as possible . We recognize that failing to address white supremacy and other oppressions means doing harm: excluding, ignoring, and marginalizing people who have been kept out of the movement. We also recognize that when we confront unintentional racism, sexism, classism and other marginalizations, we are becoming more inclusive. It is disturbing these efforts towards sincere, self-aware inclusion are seen as “divisive.” We call attention to our failures in the climate movement because we want to move forward together, with strength, ready to win.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.