(Image: Red Granite Pictures)What makes The Wolf of Wall Street so vitally important is that it illustrates that entitled, master-of-the-universe mindset that is actively mucking up the world for the rest of us. The problem isn’t that this movie encourages viewers to idolize people like Jordan Belfort – the problem is they already do.

(Image: Red Granite Pictures)What makes The Wolf of Wall Street so vitally important is that it illustrates that entitled, master-of-the-universe mindset that is actively mucking up the world for the rest of us. The problem isn’t that this movie encourages viewers to idolize people like Jordan Belfort – the problem is they already do.

Also see: The Too-Appealing “Wolf of Wall Street”

When a major studio film dealing with vital societal issues is released from a respected auteur and a top-of-his-game leading man, it’s inevitably going to leave some folks cold. There’s no way any one movie can be the one movie that sufficiently covers every pertinent angle. The best a movie can do is focus on telling a story so specific and singular that it yields many different truths. It won’t be everything to everybody.

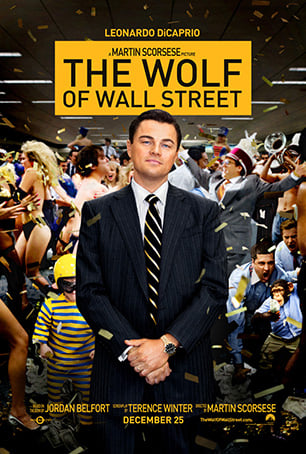

Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street adapts crooked stockbroker Jordan Belfort’s memoir into a scathing, riotous and brilliantly crafted takedown of capitalist culture and excess. However, there’s been no small amount of debate as to whether the film undermines its seeming intentions by overly glamorizing Belfort and his obscenely decadent lifestyle. Adding heat to the criticism is the fact that the real-life Belfort is almost certainly profiting in some capacity from the mere existence of his film (consider that the Wolf title came a from a hit-piece of bad publicity that became an unexpected boon to Belfort’s upstart company).

Can’t say that’s a warm and fuzzy thought. However.

While Wolf hardly begins to cover the full spectrum of ills left in the wake of Wall Street, capitalist excess and everything-wrong-with-everything, this doesn’t negate the film’s virtues. The debate it has inspired is expected and inevitable – even if Scorsese could go back in time and make every concession requested of him to more clearly vilify his villains, the same basic arguments would come up.

“Cautionary Tale”

Some criticize The Wolf of Wall Street as an insufficient cautionary tale in that its protagonist does horrible things, has a lot of fun, suffers minimal consequences and remains secure in his greed and narcissism. However the cautionary tale isn’t for people like Belfort – it’s for the rest of us who have to live in a world that caters to its Belforts.

The Wolf of Wall Street is a warning to you. It is a warning to us. While the narrative is filtered through Belfort’s manic, drug-addled perspective, this isn’t some fictional world. The harshest truths haven’t been twisted to fit a morality tale – this is still our world we’re looking at, and in our world, there are people who think like this, act like this and live like this. And what makes this film so vitally important is that it perfectly illustrates the entitled, master-of-the-universe mind-set that is out there and actively mucking up the world for the rest of us.

The problem isn’t that this movie encourages viewers to idolize people like Belfort. The problem is they already do. Our entire culture is geared around idolizing people exactly like Belfort. How many times have we heard the same exact rationalizations about wealth enabling a person to do more good regurgitated by the Belforts of the world, and how many times have we bought it without thinking critically about how that wealth is generated and what the wealth is really doing?

The Belforts of the world can derail economies. It’s happened. They can pass or neuter laws. They can take everything you have without caring, without noticing. And see, this is how it looks from the other side. Is it any wonder that Belfort’s victims remain faceless? All the victims – all of us who buy into the dream they’re selling – we’re just pocketbooks and credit card numbers. We’re just voices over the phone. This movie isn’t about us.

Nor is it about justice being served. The law enforcement agent in pursuit of Belfort is seen diligently working away in brief cut-aways, slowly building his case – but he’s always silent in these scenes. We only ever hear his voice in Belfort’s presence. In contrast, we constantly hear Belfort’s self-aggrandizement as a nonstop commentary through the film. Hey, kind of like how justice has no voice while the wealthy can afford to broadcast their perspective 24/7 in high-def! Fun stuff.

Agent Buzzkill doesn’t have any fun in the movie. The film does nothing to glamorize his work or lifestyle. It looks depressing and hopeless to do the right thing day after day while the world bends over backward for its Belforts.

Yup. That’s the point. It’s rubbing your face in it. The takeaway shouldn’t be “this movie wants me to go be a greedy scumbag like Leo!” If you get that from this movie, you probably get that from a lot of things. You might be the type who sides with the villains in Bond movies or thinks Batman should apply more social Darwinism.

Bad Wolf

Just because the movie is so good at showing the charming and attractive side of Belfort doesn’t mean it skimps on exposing him as thoroughly loathsome scum.

Helen O’Hara makes a fantastic case that the film actually has a feminist nature, in that a “viewer with even an ounce of sense should emerge from the film with the uneasy realisation that, given that Belfort’s an asshole, misogyny might also be assholish.” She spells out several of the ways the film treats Belfort and his crew with abject condemnation and disgust. Reading about it divorced from the experience of the film, it’d seem open-and-shut.

(Granted, watching a film and reading about it yield radically different experiences. We’ll come back to that.)

Sure, Belfort is shown being generous to his employees and friends – with money he’s conned from people. All the money is ill-gotten – not a single act of touted generosity is untainted. It’s easy to forget that when caught up in the emotions and actions being portrayed – that’s the criticism, but it’s also the point.

It’s also easy to overlook the less-flashy connections being made. For instance, there’s the scene where Belfort draws tears from a grateful employee with his account of helping her in her time of need. Yes, on the surface, this scene goes along with Belfort’s take of the situation and how it’s received by his audience of employees. But it’s mirrored by an earlier scene in the same office with many of the same employees partying like depraved lunatics as another female employee is paid $10,000 to shave her head – money they insist be used for breast implants. It’s hard to see the employee tear up in the later scene without recalling the dazed, humiliated woman from earlier, gaping at handfuls of cash and hair.

At the same time, while we’re watching Belfort deliver this rousing motivational speech, we’re seeing him talk himself into a hugely self-destructive decision that may also ruin the very company he’s amping up. It’s one of many “good lord, why can’t you just stop?” moments in the film. (Jonah Hill carries some of the most brilliant of them.) What gives those scenes an edge, though, is that we know the answer. We inherently understand the answer. If you could have so much, wouldn’t you want more? Look how much fun everybody’s having! Look how much fun we’re having experiencing it vicariously! Live the dream!

That aspect seems to make a lot of people uncomfortable. It should. It’s discomforting.

Leonardo DiCaprio told Variety, “This film may be misunderstood by some; I hope people understand we’re not condoning this behavior, that we’re indicting it.” What’s more discomforting is that the film also indicts the viewer as complicit – the final shots of the film set at Belfort’s seminar are particularly damning. There’s a reason we don’t see any of the victims of Belfort’s fraud – we only hear their voices. It puts us in Belfort’s position, or more like one of his misfit crew of scam-artists. It’s easy to see this as dehumanizing the victims and minimizing the human consequences of Belfort’s actions. But that’s the point – that’s what it’s like from the perspective of somebody like Belfort. This is about seeing how Belfort sees. This is about the implications you can draw from understanding that.

Charisma Conundrum

How do you communicate the appeal of something you ultimately condemn without coming off like you’re making too strong a case? Scorsese opts for excess in form and function, indulging so heavily in decadence and obscenity that the viewer’s gagging on it by the end. It’s too much for some viewers – an Academy member lambasted Scorsese for those elements, and at least one theater warned patrons in advance. Yet because DiCaprio comes off so charming (at times), some still see the film as an endorsement – some may even see Belfort as some kind of role model.

The seeming disconnect between the implicit morality of the film and the appeal of the protagonist’s immorality arises all too often in cinema. The debate is even more pertinent when it deals with true events. Another example of a film that’s drawn similar criticism that’s free of the real-life connection is Fight Club. Through the charms of both charismatic nihilist Tyler Durden and the film’s aesthetic, the protagonist and viewer are seduced into the appeal of Durden’s half-baked anarchic utopia – so much so that when Durden’s cult takes a militant turn and it’s-all-gone-too-far, viewers may still find themselves sympathizing with the ideology the film otherwise criticizes and rejects.

Fight Club and Wolf portray charismatic anti-heroes and their credos as appealing for only part of their run-times while ultimately condemning them. However, viewer empathy is a hell of a thing. On the surface, it’d be a struggle to see any appeal in the disgustingly brutal violence of the titular fight clubs – by no means did they glamorize the physical damage of engaging in recreational fistfights. Nothing about Durden’s life of scenic filth and catch-phrase philosophy is appealing in its actual substance – however, actor Brad Pitt’s performance and the film’s aesthetic lends assurance, gloss and allure to the ideas he’s presenting in order to properly seduce the protagonist at the beginning. We have a lot more fun as a viewer when we’re going along with Durden than we do when we’re against him, no matter what the less-fun scenes have to say about what’s right and wrong.

Unlike Wolf, Fight Club is more active in using cinematic and narrative techniques to extend the romance of an adolescent fantasy of anarchism to encompass the filth, decay and misery of Durden’s world. Both films trust the viewer to see through the seduction and arguably make it perfectly clear on a textual level where they stand, but inevitably we’re going to get some champion decision-makers out there half-understanding the media they consume.

The most effective, visceral moments are going to stick with the viewer more than the actual text of the film – it’s unavoidable and important to be aware of as media consumers. The strongest filmmakers can balance this somewhat to articulate their theme, but there’s only so much that anybody can control – in a production, in the edit and least of all in viewer’s minds. Belfort does unforgivable things in this movie – the danger he puts his child in at one point is particularly monstrous – but as a viewer, the scenes where you hurt yourself laughing so hard at the absurdity on display are going to stand out.

In making a movie about the intoxication of capitalist excess, Scorsese and crew have opened themselves up to the criticism that they’ve made capitalist excess seem intoxicating. You can’t do what they did so well without the possibility of it being misinterpreted. If the filmmaker punished Belfort or downplayed the allure of his lifestyle, it’d be a sham – just another Hollywood fantasy. Hell, Wall Street already gives you that take – the clear moral high ground is held by Martin Sheen’s blue-collar union president; Gordon Gekko is clearly painted as a villain and is punished with no caveats at the end of the film. Yet we still have a generation of Wall Street sociopaths who took the wrong message from it.

If we’re going to deal honestly with real issues in film, it’s inevitable that people will draw many different conclusions. And some of those conclusions can be diametrically opposed to the filmmakers’ intention. Making safer choices to restrict the room for interpretation, though, would limit and cheapen the work. The Wolf of Wall Street succeeds by focusing on the emotional truths of Jordan Belfort – the greed, the compulsion, the deceit, the appetites, the arrogance, all of it – and in doing so, it serves as a mirror for all those attributes in ourselves and our culture. And, as with most essential films, you can bet your mileage will vary. Our ability to empathize and be viscerally moved by cinema will shade every viewer’s experience and interpretation differently.

Regardless, this film isn’t inventing the next wave of Jordan Belforts, just as Wall Street didn’t invent the Gordon Gekkos nor Fight Club the would-be Tyler Durdens. They’re already out there. They’re always going to be out there. It just gave them fashion to rip off and movie quotes to run into the ground.

Matching Opportunity Extended: Please support Truthout today!

Our end-of-year fundraiser is over, but our donation matching opportunity has been extended! Today, all donations to Truthout will be matched dollar for dollar. Your one-time gift today will be matched immediately. As well, your monthly donation will be matched for the whole first year, doubling your impact.

This matching gift comes at a critical time. Trump has made it no secret that he is planning a demolition-style attack on both specific communities and democracy as a whole, beginning on his first day in office.

Help us prepare for Trump’s Day One, and have your donation matched today!