The new NBC series “Chicago PD” (created by Dick Wolf, the man behind “Law and Order”) opens with steel-eyed Detective Sgt. Hank Voight glaring coolly into a rearview mirror from the backseat of a car. We quickly learn that the man driving the vehicle isn’t chauffeuring Voight around by choice.

“I don’t know where I’m going,” whimpers the driver, a young man with a bloodied face and a seemingly broken right arm.

“Just keep driving,” gruffs Voight.

When the two finally pull off into an empty gravel lot, Voight grabs the man by a tuft of hair and yanks him out of the driver’s seat. The sergeant slaps and kicks the young man around until he crumbles to the ground in a sobbing heap.

“Who’s puttin’ out the bad dope?” Voight snarls, and when he follows up by pressing a handgun to the quivering man’s face, the latter finally relents.

“His name is Ralph! He deals out of his apartment in South Emerald!”

Within a minute and a half of the first episode, the show has summed up its central message: Police violence works. This is relayed again and again throughout the series: When a cop with a chain-wrapped fist savagely beats a Spanish-speaking suspect demanding an attorney until he relinquishes a tip; when officers debase the idea of policing without intent to arrest; when cops round up black non-criminals and deliver them to precinct torture chambers. In every episode, these methods achieve the desired ends. The message: Police violence works.

Crime dramas that embellish the lives of police officers are not new. Criminologist Yvonne Jewkes says crime drama is “the most enduring of all cinematic genres,” and television holds to the same rule.1 What sets “Chicago PD” apart from others in the genre is that police violence isn’t just presented as an exciting feature of the job; rather, its producers have made it the primary point of appeal to its growing audience of 8 million.

What does it mean that a TV show so sympathetic to police abuse has become the most popular evening program among NBC’s 18-49 demographic? To understand its appeal, it’s necessary to couch recent trends in cop media within historical transformations of public opinion toward police and federal support for local policing.

In the past 40 years, the militarization of police forces occurred concurrently with an increased emphasis on “law and order,” perpetuated by race-baiting politicians who spurred alarm among white Americans following the racially charged riots of the mid-1960s that shook white America to its core. To the prudent majority on the conservative side of the era’s culture wars, the 1965 Watts riots in LA, along with “riots in Baltimore, Newark, Washington and Detroit in the following years, were signs of a rising criminal class that was increasingly out of control,”2 as Radley Balko observes in his book Rise of the Warrior Cop. This induced a broad call for “law and order” among the white American majority by the end of the decade, and race-baiting politicians used the mandate to launch an unprecedented militarization of police forces that continues today. The threat of crime soon embedded itself at the forefront of national consciousness, and in response to that reality, Hollywood started pumping out a slew of films and TV shows centered on the lives of police officers, giving birth to a new subgenre within crime drama: the Cop Booster.

However, policy doesn’t only influence media; sociologists have found that media has a real effect on policy. Because “public knowledge of crime and justice is largely derived from the media,” the Cop Booster subgenre is part of a larger criminal-media-complex that manufactures “pervasive images of predatory criminals” that “steer [the] currents on our criminal justice policy.”3 Television programs like “Chicago PD,” a classic Cop Booster show, reproduce a narrative that that not only shields real life police forces from the scrutiny of public accountability but also engenders millions of people’s assumptions about criminality – assumptions that help keep the gears of the prison-industrial complex spinning.

The Chicago PD of “Chicago PD”

There have been 102 criminal convictions of Chicago police officers since 2000. This figure greatly understates the degree of abuses carried out by the department in recent years: Between 2002 and 2004, less than 2 percent of civilian complaints for excessive force, illegal searches, racial abuse and false arrests resulted in legal action.

By far the most well-known CPD scandal involves the systematic use of torture. From 1972 to 1991, officers brutally tortured more than 100 detained men and boys, all black, by, among many other things, burning cigarettes on their bodies, beating their faces with a flashlight and emitting powerful volts of electricity with cattle prods to their genitals.

After the news of torture broke more than two decades ago, it was also revealed that a whole crew of higher-ups had turned a blind eye to the widespread maltreatment. When a medical examiner for one of the first few abuse cases demanded a superintendent of police investigate the abuse, the buck was passed off to the state attorney, whose office essentially sat on the allegations as a culture of torture proliferated for more than a decade. Meanwhile, CPD Cmdr. John Burge personally sanctioned and participated in the torture of a number of men.

Since reporter John Conroy broke the story of torture for the Chicago Reader in 1990, attempts at retributive justice for victims have produced disparate results. In 2003, Gov. George Ryan commuted the sentences of all 163 men and women on death row in Illinois under the suspicion that some of their confessions had been elicited through torture. High-level courts have exonerated a handful of inmates claiming to have been brutalized by police. But retribution for sins committed by the CPD has been limited to a short stint in jail for Burge and a toothless report on the tortures released by special prosecutors in 2006.

The CPD’s limited reconciliation with its lurid past is symptomatic of a “Code of Silence” that seems to stick like plaque within the department. In a successful 2007 case brought against the CPD by a woman who was beaten by an officer, the federal court ruled that the Code of Silence was ingrained deeply within the department’s culture. An affidavit submitted by the plaintiff included the findings of Lou Rieter, longtime police consultant and former deputy chief of police in Los Angeles, who said, “The Chicago Police Department has created an organizational environment where the Code of Silence … [is] present and would allow police officers to engage in misconduct with little fear of sanction.”

Clearly, the team behind “Chicago PD” had plenty of source material on which to base their characters. The show features a team of intelligence officers who, like some of their real-life counterparts, torture suspects, circumvent civil liberties protections and keep tight-lipped about each other’s “off-duty” violence against innocent people.

Yet in a conversation with Southside Weekly, executive producer Danielle Gelber said that although “everything we do is grounded in authenticity … we don’t want to be making a statement about Chicago violence and how it’s dealt with by the police department.” If the producers claim that depictions of police abuse are not intended as a form of commentary, then how is the show’s realism interpreted by audiences?

#ChicagoPD

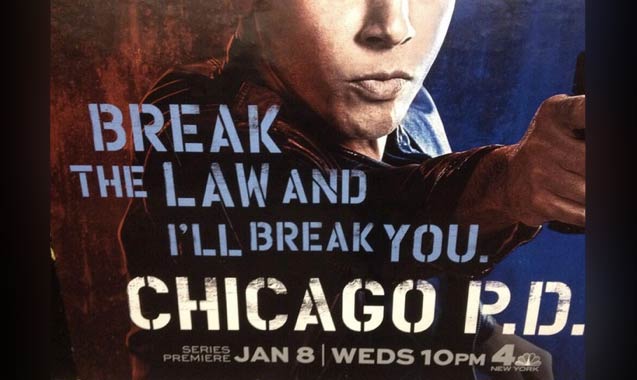

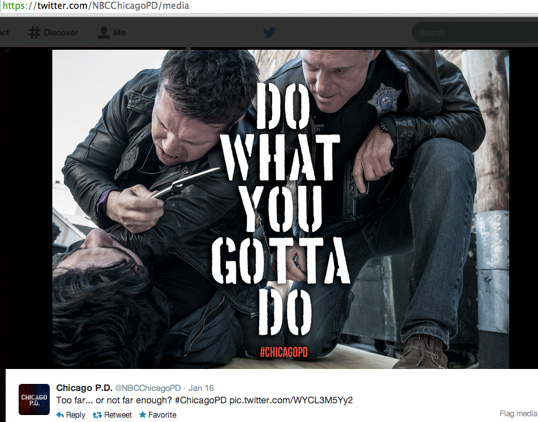

Part of NBC’s marketing strategy for “Chicago PD” has included a well-developed social media arm to engage its audience in real time.

One can peek into the minds of the show’s most ardent fans using the Twitter hashtag #ChicagoPD. Most tweets rhapsodize about the love drama developing among the extraordinarily attractive cast of officers, but a closer look reveals that show’s fantastical simplicity inculcates a sort of ignorance that benefits unfettered law enforcement power.

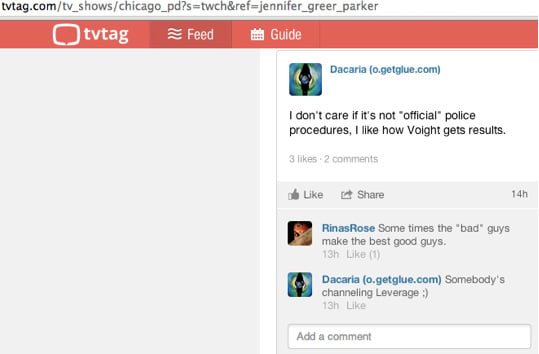

Here’s a sampling of some tweets and comments:

I don’t care if it’s ‘official’ police procedures, I like how Voight [the series’ protagonist] gets results.”

“Sometimes the ‘bad’ guys make the best good guys.”

-Dacaria and RinasRoas, TVTag

“You guys bring all of us that watch the show what really happens in Chi-Town”

-@HatJunkieNY

“Dang you guys are all crushing it!! Keep it up!!!”

-@ChristyAmiro during a scene in which an officer nearly gouged a suspect’s eye out with a dagger.

(About which, by the way, the show’s Twitter manager minced no words on their feelings):

Sharon Floyd, a fan of the show from Philadelphia, told Truthout in an email that her only encounter with law enforcement was a stop for a traffic violation, and she professed a deep admiration for those who “are not guaranteed the next day of life … or have their partner or colleagues die in front of them due to insane criminals shooting anybody and everybody.” She dismissed police abuse as an inevitable consequence of a profession.

“Like all jobs, you have the good – who follow all the rules, you have the bad – who follow their own rules and some may fall in the middle when questioned why they don’t pick a side,” she wrote.

Floyd’s rationale is shared with many fans of police dramas. One study found that regular viewers of crime dramas are, overall, more likely to fear crime. Sociologist Ray Surette, author of Media, Crime and Criminal Justice, explains in his book that “viewing television crime shows … has been found to be related to fear of crime, [and] perceived police effectiveness,” with “heavy media consumers shar[ing] certain beliefs … about a world that is seen as more violent, dangerous, and feared than the socially constructed world of those who consume less media.”4

Perhaps the most significant impact of an elevated fear of crime is its tendency to induce a desire for punitive sentencing against perceived malefactors. Studies from the past 30 years have found that “if people fear crime … they are more likely to want harsher sanctions, in the hope that offending behavior and, consequently, their levels of fear will be reduced.”

“Even if people intellectually understand that the media is fantasy, research suggests it still colors your worldview. You see the world as more violent, and it increases expectations of crime, violence and corruption,” Surette told Truthout.

Furthermore, shows such as “Chicago PD” promote the idea that crime is mostly rooted in individual motivation and choice. This presentation obscures the structural origins from which the majority of crimes stem.

“There’s social, structural [and] economic things that put people in situations where criminality happens,” Surette said. “But those issues get shunted aside and presented as wrongheaded and silly [in the media]. The thinking is, why waste time and money on that sort of thing when the problem is evil people? Evil people aren’t gonna be helped by job programs.”

The most pernicious effect of this portrayal is its potential impact on actual criminal justice policy. Criminals in “Chicago PD” and similar media are presented as terminally malicious predators who must be killed or caged, and this closely matches the carceral logic of our system of mass incarceration, which is grounded in a harsh retributive approach to sentencing.

Surette also describes how Cop Booster shows such as “Chicago PD” help cement the idea that the only way to fight crime is to give more power to police. “In these kinds of shows, the system that gets encouraged is to increase fighting capabilities, increase punitiveness of the system. … What comes off as not sensible is community integration.”

It’s still people’s actual experience with police and crime that most affect how they feel about either. But when that experience is in short supply, as it is with Floyd and possibly other “Chicago PD” aficionados, then it is reasonable to suppose that sustained exposure to crime dramas can skew one’s perception of policing matters in a way that obscures – or even vindicates – civil rights violations.

That may not mean much to those who’ve never been on the wrong end of a swinging police truncheon, but it is everything to those whose lives were ruined by the unchecked excess of punishing state power.

“The Police Cannot Be Trusted”

Jeanette Plummer is the mother of Johnny Plummer, a plaintiff in a new class-action lawsuit against the Chicago Police Department related to the Burge tortures. In 1991, when Johnny was 15, he was arrested in connection with a murder, and during the course of his interrogation police savagely beat him until he made a statement incriminating himself. After leaving his body bruised and raw, Johnny was sentenced to life in prison without possibility of parole, despite a tainted confession and an unwavering declaration of innocence. He is locked up at Menard Correctional Center, having now lived the majority of his life behind bars.

His impoverished mother can visit him only once a year because she must constantly tend to another one of her children with special needs. Decades after the torture of her son, she remains deeply resentful of the police and the legal system that failed him and his family.

“It doesn’t make sense,” she told Truthout over the phone. “The police cannot be trusted. How can they get away with doing that?”

In late 2012, a group of attorneys filed a class-action lawsuit to determine whether more than 100 men currently incarcerated were imprisoned as a result of confessions elicited through torture by Chicago police (state law renders such admissions inadmissible at trial). The new litigation may be the last hope that some of the torture victims have of challenging their convictions before they die in prison.

“I hope someone hears my baby’s cries,” Jeanette Plummer said. “That’s what I’m hoping for. And I’ll never give up. I gotta keep fighting for my son to try and bring him home.”

While Johnny Plummer and dozens of other victims serve their life sentences, Burge also passes his days behind bars, as he has since his incarceration in 2011 for lying about his knowledge of the tortures. He is set to leave prison in late 2015, after a total of four and a half years behind bars.

The Rahm Emanuel Link

No story about Chicago public service would be complete without mentioning Rahm Emanuel, the city’s hardnosed mayor, who, shortly after authorizing two multimillion-dollar settlements for two torture victims, called on the city to move forward from the scandal.

“I am sorry this happened,” he said in a press conference in September 2013, with a hint of characteristic impatience. “But we have to close the books on this. … This [settlement] is a way a way of saying all of us are sorry about what happened … and closing that stain on the city’s reputation.”

For the mayor, shows such as “Chicago PD,” featuring valiant portrayals of the Windy City’s men and women in blue, also may be exactly what’s needed to repair the department’s tattered image. Lucky for him, his own brother Ari is the head of the talent agency representing the show’s creator, Dick Wolf, as well as some of the show’s stars.

The close linkages between City Hall and the show’s producers merit discussion.

Ari Emanuel co-founded the talent agency Endeavor Agency in 1995 with a man named Rick Rosen. That agency became the William Morris Endeavor (WME) after a merger in 2009. Ari Emanuel is co-CEO of WME, and Rick Rosen is a board member and head of the television department. The two men still work together in a very close capacity; recently, Oprah quit her old agency and signed on to WME, “where her career will be handled by a team of agents led by Ari Emanuel and Rick Rosen.”

Rosen also has been Wolf’s agent since at least 2009. The two men reportedly are close and work together in other ventures as well: Both are advisers in Wolf’s media think-tank, the Carsy-Wolf Center.

Wolf was able to leverage his proximity to the Emanuels to score a cameo of the mayor for his other show, “Chicago Fire.” Rahm made an appearance on the series premiere under the condition that the show made an investment to the firefighters’ widows and orphans fund.

That show, which was a runaway success in 2013, is to the Chicago Fire Department what “Chicago PD” is for the police: a cartoonish representation of public service heroism that, for Rahm, meant “jobs for Chicago,” in the words of one source to The Hollywood Reporter.

Could this be a sign of Wolf’s willingness to scratch the backs of Ari and Rahm in return for industry credence after NBC’s producers snuffed out Law and Order: LA in 2011 after only a year of airtime?

One thing is for sure: Given the extremely close relationship between the Emanuel brothers, it’s not likely Ari’s agency would represent anyone with something bad to say about Chicago.

Good and Bad

The pull of crime dramas and the Cop Booster subgenre is that they allow us to escape into exciting, hyper-violent worlds where it’s easy to know who is good and bad.

The insidious side of society’s infatuation with simplistic dichotomies of benevolence and evil is how it undercuts the nuance with which real-life social and political problems must be confronted. Law enforcement agencies regularly invoke images of “good guys and bad guys” to sell their policies – even in Congressional hearings – and the effect is the broad acceptance of a framework that uniformly criminalizes whole classes of people.

A major consequence of this framing is that it makes it easier for aggressors in power to push their agenda. Any threat perceived as innately, unalterably evil is reduced to a social punching bag. You can bomb it, shoot it, cage it, kill it – including by injection it with poisonous chemicals. But the one thing you can’t do is change it.

Our criminal justice policy reflects the idea that those who break the law must be punished swiftly and mercilessly. Punitive policing, three-strikes laws, mandatory sentencing, solitary confinement and the death penalty all fall into that category. They are practices rooted in a violent, Hobbesian vision of the world in which the good must be protected from the bad. Unsurprisingly, rates of incarceration indicate that race and class are strong determinants of the side on which one falls.

The media plays a central role in reproducing and perpetuating this paradigm. The police in “Chicago PD” are good, and they care so deeply about justice that they will do whatever it takes rid the world of the bad – even if that means torture. TV series such as “Chicago PD” not only help to normalize police brutality and corruption, they also sharpen the mythical edge that divides good and bad people, justifying the deeply flawed underpinnings of the US criminal justice system. In that worldview, police violence works.

NOTES:

1 Jewkes, Yvonne. Media & Crime. Los Angeles: SAGE, 2011. Page 183.

2 Balko, Radley. Rise of the Warrior Cop. New York: Public Affairs, 2013. Page 53.

3 Surette, Ray. Media, Crime, and Criminal Justice. S.l.: Cengage Learning, 2014. Page xvi.

Defying Trump’s right-wing agenda from Day One

Inauguration Day is coming up soon, and at Truthout, we plan to defy Trump’s right-wing agenda from Day One.

Looking to the first year of Trump’s presidency, we know that the most vulnerable among us will be harmed. Militarized policing in U.S. cities and at the borders will intensify. The climate crisis will deteriorate further. The erosion of free speech has already begun, and we anticipate more attacks on journalism.

It will be a terrifying four years to produce social justice-driven journalism. But we’re not falling to despair, because we know there are reasons to believe in our collective power.

The stories we publish at Truthout are part of the antidote to creeping authoritarianism. And this year, we promise we will kick into an even higher gear to give you truthful news that cuts against the disinformation, vitriol, hate and violence. We promise to publish analyses that will serve the needs of the movements we all rely on to survive the next four years, and even build for the future. We promise to be responsive, to recognize you as members of our community with a vital stake and voice in this work.

Please show your support for Truthout with a tax-deductible donation (either once today or on a monthly basis).