Part of the Series

The Road to Abolition

In 1995, my life was dangerously shifting on shaking ground. The monkey on my back was consuming more drugs than usual: more crack, more weed, more booze, more pills. Pretty soon I was in unsurmountable debt; more than I could afford. Then came the irrational decision — the ones you tend to make when riding high and in need of more gas — to make an extra buck.

A so-called friend and I obtained some cocaine from a drug dealer to sell to another so-called friend, only to learn that upon the delivery of the cocaine, both so called-friends would disappear, never to be seen again. A set up? Unlikely. Part of the drug game? More than surely.

Without a cent to pay back the drug dealer who provided the cocaine on consignment, the $240,000 drug debt rapidly became the number one thing to pay back by any means necessary; that is, if I wasn’t willing to lose my life and the lives of my family.

Based on the coercive suggestion of the cocaine dealer, I agreed to make trips with marijuana smugglers from the U.S. and Mexican border to Houston, Texas, to pay back the drug debt. “After all, it’s only weed,” I rationalized, blindly unaware that the “war on drugs” was at its peak, and all it would take was for one of my crime partners to snitch on me and I would be down for the count. Gone for good. For no matter the amount, a federal conspiracy to distribute marijuana comes with a price tag of a lot more than what you bargain for.

I eventually transported marijuana bundles from the border to Houston and sold them to the highest bidder, well into 1996, until the drug debt was settled with the cocaine dealer. Then I went on my way, still feeding the monkey, but now with less frequency, thinking everything would be all right.

Not so.

Over time, the marijuana smugglers were arrested one by one and started singing to save their own hide. My name was thrown into the mix, and a Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) warrant was issued for my arrest.

That spring morning of May 27, 1998, came like a bad nightmare (one that’s still troubling me to this day). I was living in a two-bedroom apartment with my wife Sara, who was three months pregnant, and my 3-year-old son, trying to hold onto a job selling cars while still wrestling with drug addiction. Everything seemed like a normal day on my way to work, save for the pounding headache and the slight nausea from heavy drinking the night before. As soon as I stepped onto the back of the parking lot of the apartment complex, I was surrounded by the Texas Gulf Coast Task Force, Houston police officers and DEA agents, dressed with bulletproof vests, aiming AR-15s and 12-gauge shotguns, hysterically ordering, “Get down motherfucker! I’ll blow your head off!” while a helicopter hovered high in the sky. Everything felt like a slow-motion picture. Like a dream. But as soon as my body hit the asphalt with a knee crushing my back and a gloved hand holding my face down against the pavement, reality set in. This wasn’t a movie. This wasn’t a dream.

“Are you Edwin Rubus? Tell me your name?!” Several officers yelled at me. “Check his pockets and forearm.” I heard an officer say over to my right. After I was searched, another agent said, “Yeah, we got ’em. It’s him.” I was handcuffed and thrown into the back of a Houston police cruiser. I was driven to the front of the apartment Sara and I were renting. More than 15 law enforcement officers brusquely entered my apartment, ransacking it from top to bottom, from tip to tail, searching for illegal substances and weapons.

After an hour, one of the officers came out of the apartment, shaking his head, saying, “No guns, no money, no dope … bummer!” while my wife and my son silently stood there traumatized by the unexpected turn of events. “He’s being arrested for conspiracy to distribute marijuana,” the DEA agent in charge informed them. My wife was as baffled as me as to what those charges meant.

A day later, I stood in front of a magistrate judge. He again informed me of the charges, but with more details. “You are being charged with the selling and distribution of 1,000 kilograms of marijuana. You will be held without bond until you decide to plead guilty or proceed to trial.”

After the arraignment court proceedings, my court-appointed attorney said, “All your charges stem from the testimony of your crime partners. They are vehemently cooperating with the government and the DEA for a reduced sentence. If I were you, I’d play ball and start snitching, or things will look grim for you.” I didn’t respond. “Think about it,” he concluded, sitting there with a lazy smile across his face as if he was having a friendly conversation with one of his buddies at happy hour — except I was shackled and fettered to a metal chair inside a jail cell.

And just like it happens in the movies, ignorance of the law got the better of me. I refused to snitch and play ball. Instead, I proceeded to trial firmly believing I’d prevail — since “no money” “no guns” and “no dope” were found on me. But little did I know that a conspiracy charge can easily be established by the testimony of two or three individuals under hearsay basis to obtain a conviction. Little did I know that my crime partners had extrapolated the amounts of marijuana we had smuggled from the border to Houston, and if I were found guilty, the sentencing judge could sentence me up to life in prison based on those inflated numbers.

In the climax of things, more than a handful of parrots testified against me, each repeating what the other had said, as they all had been housed together close to a year in jail and coached by the DEA and the Assistant United States Attorney before trial. After being found guilty, the judge sentenced me to a de facto life sentence of 40 years (meaning I’d have to serve 34 years of my life behind prison bars). “For putting us through the difficulties of trial and for him not playing ball,” I overheard the prosecutor whisper to my court-appointed attorney right after the final court proceedings. Shackled and chained, I was swiftly led out of the courtroom by U.S. Marshalls, taken down a service elevator, into a waiting van, on my way to federal prison.

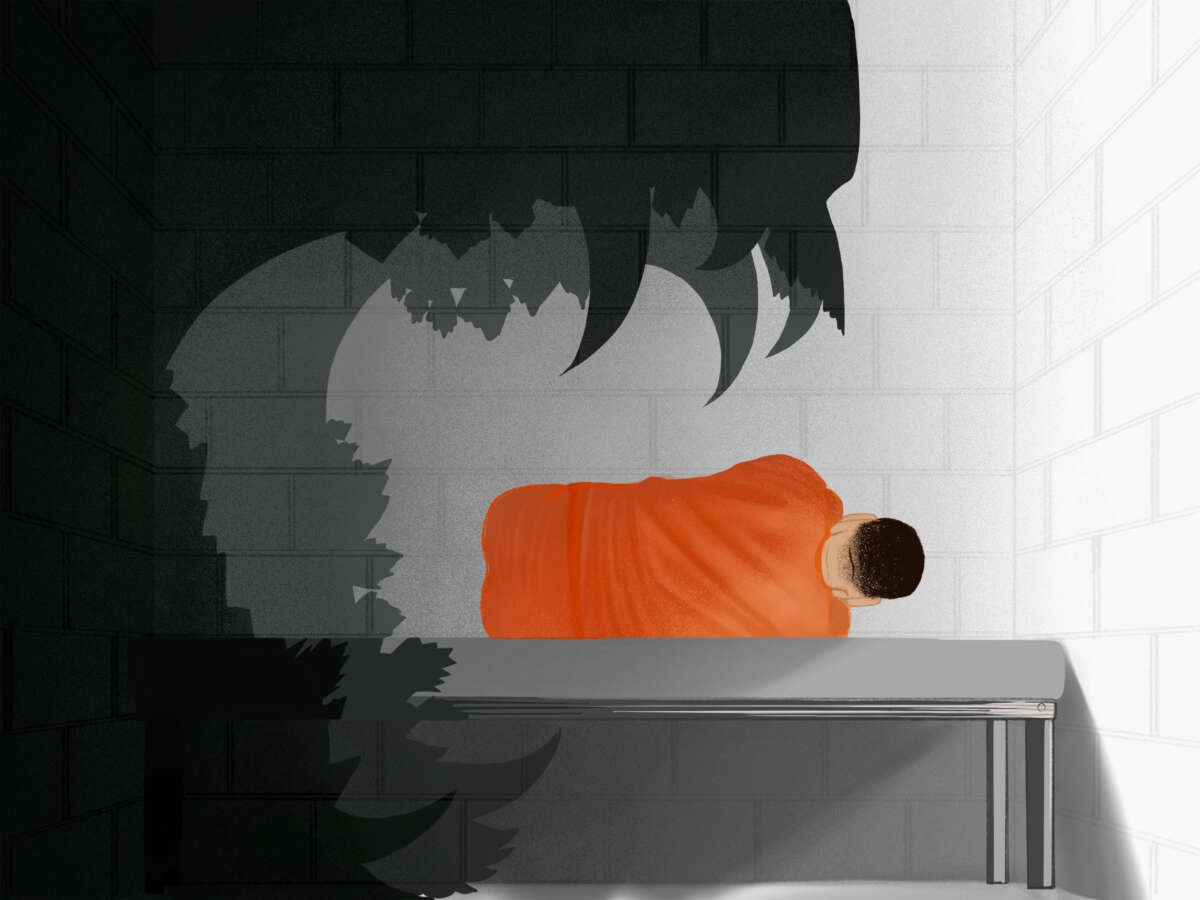

Right after entering one of the most violent prisons in the United States, depression set in. I was being ripped away from my family for decades on end for a nonviolent marijuana crime, mostly due to my irrational choices. Every time I’d call home, one of my sons would always ask, “Dada, Dada, when you come home?” This always pained me to the core. “Soon, son, soon,” I’d always answer, knowing full well “soon” meant an undetermined length of time.

My first prison visit was heart wrenching. Keanu, my 3-year-old, couldn’t sit still. He kept tugging on my shirt, trying to pull me away from the visiting table and pointing toward the front door. “Dada, go home. Dada, go home,” he pled. When our visit was over, he wouldn’t let go of me. He started crying uncontrollably. The prison guards had to intervene. After more than a few comforting attempts, he finally calmed down.

Over time, the emotional turmoil and the longing for my family finally took its toll. Seeing no way out, I tried to take my own life, something I now regret. At the time, though, it seemed like the only way to escape my emotional pain was to end it all. By God’s grace it didn’t happen. I was eventually put on suicide watch and received psychiatric counseling. In time, I learned to accept the fate that I wasn’t going anywhere; that I’d have to endure whatever came my way in the years to come. Not long after, in 2001, I was diagnosed with a life-threatening illness. On the verge of dying, and close to cashing in the check, God’s grace again intervened. I didn’t perish. But I was still left with a handicap of only being able to walk short distances for months. And then, two years later, the worst news hit the deck. Sara unexpectedly left me. She took the children, eventually remarried, and moved on. I don’t blame her. A wife isn’t expected to serve out 40 years alongside her husband while he’s in prison, patiently waiting for him to come home.

The past 24 years of my incarceration haven’t been easy. Every day I wake up surrounded by 12-foot chain-link fences, topped with looping strands of razor wire, inside a prison cell adorned with a metal bunk, a paper-thin mattress, a burlap sack like blanket, a faded plastic mirror, a rusted wash basin and toilet, and a molded plastic-chair on its last leg. The walls faded white. The door opaque blue. There are times when I feel unspeakable loneliness, anger and frustration over my unjust, dismal situation. This is sometimes amplified by the unending orders of my captors telling me when to wake up, when to go to sleep, when to use the phone and e-mail, what books to read and not read, and even when to pray.

If I am to see the light of day, cannabis laws need to change. As it stands now, 65 percent of the U.S. population approves of cannabis consumption; 37 states, three U.S. territories and the District of Columbia allow medical use of marijuana and 19 states allow it for recreational use; and just recently Missouri, Arkansas, and North and South Dakota submitted a ballot to legalize marijuana. This trend will continue until the entire nation has in some form or fashion legalized marijuana.

Then there’s the profit margins of this newfound cannabis industry. The billions of dollars it currently generates should be more than enough to say, “Let the ‘pot people’ out of prison, we are making a killing out here.” Sadly, no one takes this to heart. Even ex-House Speaker John Boehner, who during his political term was adamantly opposed to cannabis legalization, has now gotten on the board of multistate cannabis company Acreage Holdings, and is more focused on making a buck than advocating for the cannabis prisoner.

And while President Joe Biden pardoned 6,500 people for simple possession, and pardoned six more before 2022 came to a close, he need not forget about us — the ones in confinement. The ones who are serving harsh sentences under repressive, outdated, racist cannabis laws that no longer serve any purpose for our society; laws that tend to ostracize and oppress minorities; laws that need to be repealed and done away with once and for all, vomiting out the poison of carceral oppression which has previously led to a dead end, under the name of “law and order.”

Under this premise, Biden can easily use his executive power and release all the cannabis prisoners from federal prison, fulfilling the promises he made during his presidential campaign in 2020. But then again, presidential promises are often clothed under the mantle of presumed intentions: Promise the voters redress and just resolution on specific issues then renege on such promises once power has been acquired.

At this point, without clemency from President Biden, my hands shall remain shackled for another 10 years, until 2033. By then, I’ll have served 34 years in federal prison for a nonviolent marijuana crime. My parents will most likely be dead by then. My sons will in their mid-thirties. A long way from when I left them back in 1998, when one was five, the other three, and the third was not yet born.

The only illusion of reprieve left for me now lies in the dim hope of faith that someone would remember me; that someone would speak on my behalf; that someone would help set me free. But then once again, that illusion is only an illusion — under a slogan I once heard, “Ninety percent of people don’t care about your situation, and the other ten, well, they are just glad it happened to you.”

Truth be told, I will likely continue living my days in federal prison, enduring the unfair sentence I have received for selling marijuana, until I have fulfilled the judicial decree from my sentencing judge: “I want him to serve every single day of those 40 years in a maximum-security prison … until he learns not to sell marijuana to the American people.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $27,000 in the next 24 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.