The progressive movement in this country owes thanks to the new generation of workplace organizers, who are carrying our movement forward. Among them are four activists we should recognize and support: Laurence Berland, Rebecca Rivers, Paul Duke and Sophie Waldman, who were fired from Google for organizing their fellow workers.

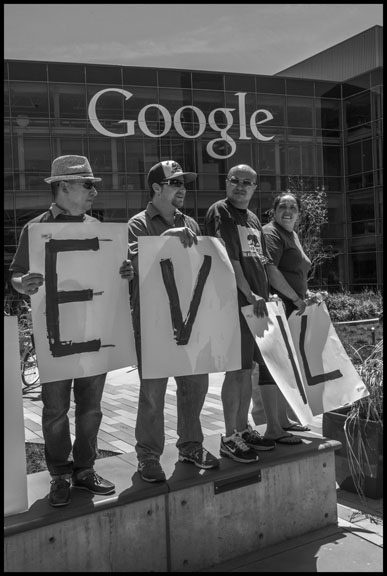

Workers at Google have been protesting many of the company’s actions over the last two years. A year ago, Google’s decision to pay a reported $90 million in severance to a manager accused of sexual harassment sparked a walkout by an estimated 20,000 employees worldwide. Petitions and rallies at its Mountain View, California, headquarters, protesting other company actions, have followed. With the firings, Google has finally sought to eliminate those workers it thinks responsible for this upsurge.

The four fired employees filed a formal complaint against Google with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), saying they were fired for collective activity, which is protected, at least in theory, under federal law. The Board is investigating the charges. Google says it would never retaliate against workers for such activity — a boilerplate denial that comes from every employer charged with violating Federal labor law. The company insists they were fired for accessing information that is readily available to employees on the company database.

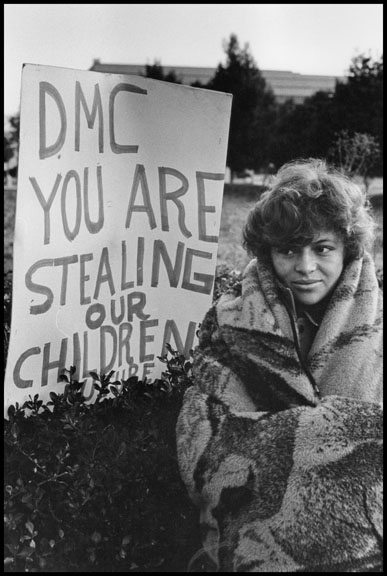

What did the four really do? They tried to put human rights into action inside the company. They protested sexual harassment. They told Google not to bid on a Trump contract to put the Homeland Security database into the cloud, facilitating the shameful detention of children and parents. They questioned Google for hiring Miles Taylor, who was chief of staff to Trump’s Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen.

What did Google say their crime was? Making sensitive information public. CEO Sundar Pichai, whose salary in 2016 was almost $200 million, told an “all hands” meeting (a Google term for a meeting for a large number of employees) that “you’ve clearly seen the amount of leaks we are seeing.” The four fired workers were Google’s own whistleblowers. When company managers questioned Rivers, the contract with DHS is what they asked about.

So, of course, Google did what the government does to whistleblowers — what union organizers call “corporate capital punishment.” It fired them. But the real reason is obvious: They were organizing their fellow workers inside the company. And Google was afraid.

“This isn’t really about me, or Rebecca, or any individual,” Berland said at a November demonstration. “They are retaliating against us because they want to intimidate everyone who dares to disagree…. They want us afraid, and they want us silent.”

Corporate media have said this is about changes in what Google boasts as its “open culture.” I know all about the open culture of Silicon Valley from personal experience.

Challenging Exploitation in Silicon Valley

When I was fired for organizing a union at National Semiconductor (a large manufacturer of integrated circuits, which had over 10,000 people in our plant at the time I worked there) I went up the food chain all the way to the office of the CEO, Charlie Sporck. He came to work in a pickup truck, wore Pendleton plaid shirts and tried to make us think he was just an ordinary worker like us. I told Sporck I thought I was being fired for organizing, and that my rights were being violated.

It made no difference — I still got fired. And after I got fired, I got blacklisted. I was never able to work in the industry again.

Many of my fellow activists also got fired for organizing the union — at National, at Phillips, at Intel. Did we get our jobs back? No. For that, you need a union with a contract that says you can only be fired for a just cause. Federal law says we can’t be fired for organizing a union, but there is no real enforcement. We all filed charges, as the workers have done at Google, and after an “investigation,” the company’s pretextual excuses were found valid. Our government is not committed to our rights at work.

My friend Romie Manan survived the firings because National Semiconductor feared him as the leader of the Filipinos in the plant. The prospect that they might organize and protest was a much more serious threat to National than a possible NLRB complaint. Today Romie only has half a thumb — the other half was burned off by hydrofluoric acid in a so-called “clean room.” His was just one of many injuries and health dangers we protested as workers.

Still, we won some things at National just because we had a group of organized workers inside the plant. That’s how a union starts. And that’s what the Google workers were fired for trying to organize, whether you call it a union or not.

We got one of the worst cancer-causing solvents — TCE, or trichloroethylene — banned. We had the help of allies in our community — the Santa Clara Committee for Occupational Safety and Health, and especially attorney Mandy Hawes, who’s spent a lifetime suing high tech companies for harming workers, and Ted Smith, who organized the Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition. They should get an award for so many years of fighting.

We forced the company to give us raises. We challenged the racist structure of high tech, where women and people of color are a big majority on the bottom, and things get more male and more white the further up you go. When I worked in the plant, the company and the government treated the racist structure of the workforce as a trade secret. Making it public began with a fight by workers in our factory.

In the 1990s, tens of thousands of us, the people on the bottom, lost our jobs when the semiconductor companies decided that labor was cheaper elsewhere, where workers weren’t trying to organize. The Santa Clara County Human Relations Commission, and its director Jim McEntee and chairman Jesus Ruiz, held hearings about racist firings in electronics plants and the relocation of our jobs. The union in the plant found workers who came to testify, risking their jobs.

That’s a lesson for the folks at Google: Our jobs can be moved. If we want to protect them, we need allies throughout our community. We have to reach out far beyond that nice Google campus in Mountain View.

We need to accept without question our right to advocate and speak freely for human and labor rights. That should include the right to speak out and organize at work. But remember what Rivers, Berland, Duke and Waldman were fired for. We cannot accept that we have rights outside the workplace but tyranny inside. You can call it open culture if you want, but we can see the iron fist in the velvet glove.

Google hired union busters, IRI Consultants, to fight its own workers. Just hours after a meeting with IRI, Google managers installed a tool allowing them to know when any worker organizes an event with more than 100 participants. What kind of event do we think they’re afraid of?

Like any corporation, Google’s loyalty is to its shareholders, not us as workers, or to us as the community dependent on the jobs. One of the signs at a Google rally said, “This is our company.” Another said, “Bring them back.” Google workers deserve credit for being brave enough to come out and wave those signs in front of company managers.

But to make it “our company” — that is, a company where workers are free to advocate progressive values, and human and labor rights — we have to bring them back, as the other sign said. That is, we need to put the four fired workers back to work, stop the company from firing anyone else, and reduce the fear that any reasonable worker feels when she or he thinks about doing what they did.

We Need to Build Broad Solidarity to Support All Workplace Struggles

So how do we do this? What difference would it make to other workers if Google workers build an organization in their company? We are told that the world of high tech is unique, and that the community and labor solidarity that won enormous changes for farmworkers, for instance, have no relevance in Silicon Valley. Our experience, however, says just the opposite.

Organizations like Jobs with Justice have already shown us how communities can organize to support the rights of all the workers in a given place. For example, organizers can set up workers’ rights boards where community leaders, faith activists, elected officials and union people join together to expose violations of rights at work, and defend people when those violations occur. When companies have to pay a price for violating workers’ rights, they’re much less likely to do so, even when the legal system doesn’t impose significant penalties.

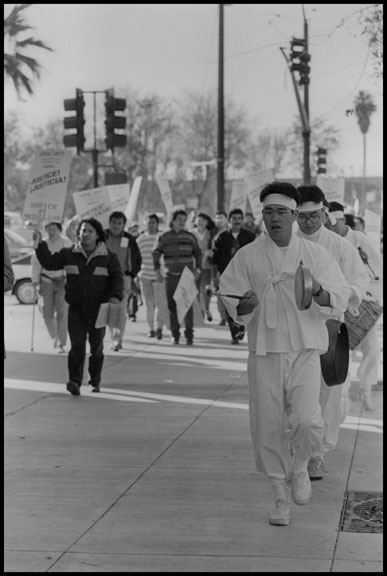

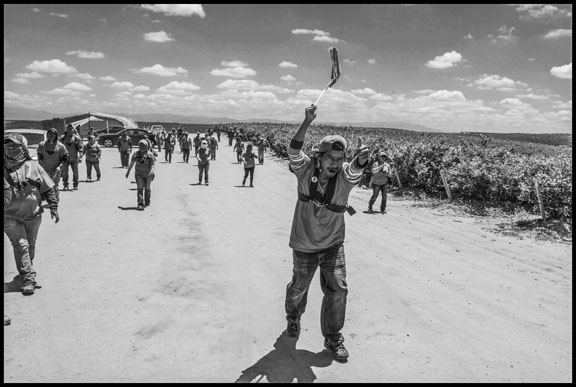

We can fight for labor law reform that restores our rights. Farm workers, for instance, still have the right to secondary boycotts. That’s a big reason why the United Farm Workers won the 1965 grape strike. We stood in front of Safeway and said, “Don’t go into the store if it’s violating workers’ rights and selling grapes during the strike.” We picketed not just the vineyards where workers were on strike but also the stores that sold the struck grapes, appealing to workers far removed from the fields to support the strike. That’s the right to solidarity in action — people supporting each other.

In the Cold War, we lost that right for the rest of us, when Congress passed the Taft Hartley Act. That law prohibited those boycotts, as well as other ways workers can support each other. We need that right to solidarity back. That can give us a tool to enforce our rights, at Google and everywhere else, and not just on paper.

That strike in 1965, and the way the boycott transformed public support into active solidarity, lifted conditions for farmworkers. It gave women bathrooms in the fields, where before there was no privacy. It gave more workers shade in the 100+ degree sun and hoes that you can use standing up, instead of the short-handled hoe that forces you to work bent over all day, in constant pain.

Our rights, especially the right to a union, have been won at a terrible cost. We remember who died for farmworker rights. Juan de la Cruz, an immigrant from Mexico, and Nagi Daifullah, an immigrant from Yemen, were shot on the picket line in the 1973 strike. Rufino Contreras was shot in a struck Imperial Valley lettuce field. Nan Freeman, a Jewish girl of 18, was run down by a truck crossing a strike picket line in Florida. They died because they believed in justice, not as an abstract principle, but as a fundamental right at work that has to be fought for.

The reasons why people organize at Google may be different from the reasons that motivated farm workers, but winning the right to organize was the key to making farm conditions better and it is the key to what Google workers hope to achieve as well. We need to stand up in the same way.

We can see that what happens to Google workers can make it harder for us to defend our rights elsewhere. If Berland, Rivers, Duke and Waldman stay fired, and people at Google get scared, IRI Consultants will show up next at the county building, or at the school district, or on construction sites. It will be harder even for people who have unions and rights at work to keep them.

If people at Google are fired for organizing against a contract with Homeland Security, it makes it harder to fight the Trump agenda of deportations and detentions.

But let’s look at it the other way. If we have strong unions at Google and Microsoft, run by militant workers, it will be easier to win the things we need, like the Green New Deal or Medicare for All or immigration reform. We can end the wars that have gone on for years. Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King warned us half a century ago that U.S. bombs that kill people abroad become bombs that explode and wreak poverty and devastation in our neighborhoods here at home.

In Silicon Valley, a human rights advocacy group called Human Agenda promotes the values of all of us: Freedom from oppression and racism. Life in a healthy environment. Social conditions that favor meaningful lives. And economic justice is one of the most important of those conditions.

If we don’t have a union at Google, we can still fight and win some of these things. But organization at work gives workers the power to fight politically as well, in the communities where we live. When workers in high tech have a strong organization, meeting our human needs and enforcing basic rights, and even goals beyond this, will be within our reach.

Organizing is the key to what we want. Our problem isn’t that we don’t know what we want. It’s that we need the ability to make change happen. And that is the product of organizing, nothing else.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.