Part of the Series

Planet or Profit

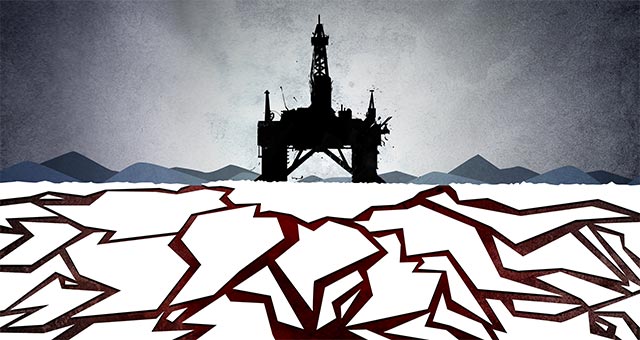

Shell Oil’s recently approved exploration in the Arctic Chukchi Sea is one of the most highly scrutinized drilling operations in the world, but, a watchdog group claims, the company has nevertheless managed to keep many of its plans hidden from view.

The watchdog group, Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), claims that Shell and its government regulators have failed to share much of the information on the safety and reliability of the operation with the public.

Last week, as activists in Portland blockaded an icebreaking vessel bound for Shell’s drilling sites, PEER filed a lawsuit against federal offshore drilling regulators demanding they disclose a range of documents detailing mandatory third-party reviews of Shell’s drilling plans and blowout prevention system, as well as disclose results from tests of its spill containment systems and oil spill response drills.

To see more stories like this, visit “Planet or Profit?”

“[Shell and its regulators] still will not release their certifications where we can be clear that they have done their compliance, that they have done their job,” said Rick Steiner, a marine conservationist and former University of Alaska professor. “Shell says everything is fine but they won’t show it.”

Police removed the Portland blockade last Friday, marking the end of a multi-tactical campaign by environmentalists and grassroots activists to stop the Arctic drilling before it starts.

Environmentalists argue drilling in treacherous Arctic conditions is dangerous and would only produce more fossil fuels, which contribute to the ongoing process of climate change that is causing Arctic ice and ecosystems to dwindle away in the first place. Other oil companies have said they would not drill in the Arctic because it is too risky.

Indeed, Shell’s first attempt at drilling in the Chukchi in 2012 ended badly when the company was forced to cancel its operations after a series of embarrassing mishaps and accidents, including a 155,000-gallon fuel spill and the complete failure of its oil spill containment system during test runs in the calm waters of the Puget Sound.

Steiner, who is also a PEER board member, said Shell is already positioning its fleet and beginning its drilling operations, but the real risk begins next week, when drilling is expected to hit the zone where vast oil and gas reserves are thought to be waiting deep below the sea floor.

Shell was required to test its spill containment system again this time around, but it remains unclear how well it performed. Steiner told Truthout that the public deserves answers to these “technical risk-management questions” before Shell begins drilling in “high-risk hydrocarbon zones.”

“We want to see the records, we want to see exactly what they did to function test this and exactly how it performed,” Steiner said.

On June 8, Steiner and PEER filed a request under the federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) with the Bureau of Safety and Environmental Enforcement (BSEE), one of the two federal agencies that regulates offshore oil drilling, requesting the records on the reviews and field tests of Shell’s drilling and emergency response plans, according to PEER’s legal complaint.

The group also asked the BSEE to release records of any whistleblower provisions put in place to allow Shell workers and contractors to report potential hazards without fear of retaliation.

After some back and forth with the agency to clarify the request, BSEE informed PEER on July 27 that it would take more than 12 weeks to gather the requested records. The agency had already extended its own deadline for responding to the request by several weeks.

PEER quickly filed suit, claiming that federal law requires agencies to process such requests much more quickly. Steiner said the request is time sensitive because Shell only has until October to drill before the harsh Arctic winter sets in, so the 12-week extension could keep the records under wraps until after the drilling is complete for the season.

Steiner said BSEE’s “inability or unwillingness” to release the records before the drilling season is “inexcusable” because “BSEE should have most of this information at its fingertips.” He said that the type of information requested should already be posted to BSEE’s website.

“That is an absurdity that nobody can stand for … it is outrageous that we have to press to get this,” Steiner said.

A spokesmen for BSEE in Alaska told Truthout that the type of documents Steiner and PEER requested are likely to contain proprietary business information and must be processed in accordance with federal law, so the agency does not publicize such documents on a routine basis.

“The government and Shell have told us, ‘Everything is fine, trust us, be happy,’ and that’s where we were before the Exxon Valdez,” Steiner said, referring to the tanker that caused the massive oil spill off the Alaskan coast in 1989. “That’s where we were before Deepwater Horizon, and we are not going to do that again.”

BSEE was created during a period of regulatory reform after its predecessor agency, the Minerals Management Service, failed to adequately anticipate and respond to the deadly 2010 explosion on BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig that caused the nation’s worst oil in spill in history in the Gulf of Mexico.

“We are simply asking BSEE to document how it functions as an independent regulator of the oil industry, but we have yet to receive an answer – which perhaps is the answer,” PEER Executive Director Jeff Ruch told Truthout in a statement. “Frankly, this information should have been publicly posted already to give the public some reason for confidence after previous fiascos in this arena.”

In June, a federal court ordered BSEE to release records on the use of fracking technology on offshore platforms in the Gulf of Mexico to an environmental group that originally requested records under FOIA. Truthout filed its own request for Gulf fracking records in November 2014, and the agency came under fire this spring for dragging its feet in responding to both requests.

“These industries don’t want citizen engagement in oversight,” Steiner said. “They just don’t.”

Speaking against the authoritarian crackdown

In the midst of a nationwide attack on civil liberties, Truthout urgently needs your help.

Journalism is a critical tool in the fight against Trump and his extremist agenda. The right wing knows this — that’s why they’ve taken over many legacy media publications.

But we won’t let truth be replaced by propaganda. As the Trump administration works to silence dissent, please support nonprofit independent journalism. Truthout is almost entirely funded by individual giving, so a one-time or monthly donation goes a long way. Click below to sustain our work.