Sue and James Franklin run a rock and mineral shop in Balmorhea, Texas, a small picturesque town known for hosting the world’s largest spring-fed swimming pool. Their shop is about 15 miles from their home in Verhalen, a place they describe as too tiny to be called a town — only about 10 people live there. The couple never imagined the area, on the southwest edge of the Permian Basin, would become an industrial wasteland, but they say that transformation has begun the last two years.

Texas’ latest oil boom, driven by the fracking industry and crude oil exports, has brought skyrocketing air, noise, and light pollution to small southwest Texas towns and the surrounding lands which are known for majestic mountain views and brilliant starry night skies. With the oil industry come bright lights illuminating an otherwise almost perfectly dark sky. The Franklins’ home on a narrow rural road is now surrounded by fracking sites. On a clear day they can see 20 of these sites from their 10-acre plot of land.

The roads in the area used to be empty, but that’s no longer the case. Today, increased traffic — mostly trucks serving the oil and gas industry — makes even pulling out of the Franklins’ driveway dangerous. James, a Vietnam veteran and retired pilot, has been in a couple accidents caused by truck drivers that “don’t give a shit.”

Meanwhile, the famous pool located in Balmorhea State Park — known as “the oasis of West Texas — has been shut down for about a year due to cracks in its structure, which some locals blame on vibrations from drilling operations nearby. The parks department, however, blamed erosion.

The changes make Sue Franklin sad. “What we are doing to Mother Earth is going to catch up with us,” she told me when I visited in early November. “She is going to wipe the planet clean and start over without us at this rate.”

The Permian Fracking Expansion

The Permian, one of the most prolific oil and natural gas basins in the US, spans approximately 86,000 square miles in West Texas and southeastern New Mexico.

Until recently, there had been little development in the furthest southwestern portions of the Permian’s Delaware Basin. But that changed in mid 2016 after the Apache Corporation announced its discovery of an oil field there called Alpine High. Apache estimated that the oil field contains 75 trillion cubic feet of gas and three billion barrels of oil.

Shortly after Apache’s discovery, the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) announced finding another 20 billion barrels of oil in the Wolfcamp shale, located in the northeast reaches of the Permian Basin, near Big Spring, Texas. The agency called the deposit “the largest estimated continuous oil accumulation … assessed in the United States to date.”

Despite scientists’ warnings that catastrophic climate change could be unstoppable if greenhouse gas emissions are not greatly reduced — including a dire federal climate report released today — numerous companies, such as ExxonMobil and Chevron, are producing record amounts of oil and gas in the Permian Basin. The EIA predicts that the Permian region will drive US crude oil production growth through 2019.

Apache and other oil and gas companies drilling in the Permian Basin use hydraulic fracturing (fracking), a process that injects a highly pressurized mix of chemicals, water, and sand to release oil and natural gas trapped in shale rock deep underground. In the basin fracking is done primarily for oil, but up with the oil comes methane, the main component in natural gas, and other volatile organic compounds (VOCs), including the carcinogens benzene and toluene.

When Fracking Comes to the Neighborhood

I met with the Franklins on November 1, and standing in their yard, I saw some kind of fracking industry site in every direction I looked.

Though most people in the area welcome the money the fracking boom can bring, the Franklins have only seen unwelcome alterations to the once starkly beautiful landscape that first attracted them to Verhalen. These days truck traffic constantly passes their home and a persistent haze blurs their view of the Davis Mountains, which is also obscured by giant tanks on the frack sites around them.

The couple now also worries about the potential health impacts of the pollution from the frack sites on both them and their animals, which include a cat, horse, and donkey.

Though the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences states there is little data conclusively showing how the fracking industry affects nearby communities, a report published by the nonprofits Partnership for Policy Integrity and Earthworks shows that the Environmental Protection Agency has identified health hazards for dozens of chemicals used in fracking.

According to Environmental Working Group scientist Tasha Stoiber, “hazards from the chemicals used included irritation to eyes and skin; harm to the liver, kidney and nervous system; and damage to the developing fetus.”

In addition, the Concerned Health Professionals of New York and Physicians for Social Responsibility, a group involved in a Nobel Peace Prize-winning campaign to abolish nuclear weapons, released their latest in a series of reports examining evidence of the public health and safety risks of the fracking industry at large. Their findings show the Franklins’ worries are not unfounded.

This report, released in March 2018, states that: “Our examination … uncovered no evidence that fracking can be practiced in a manner that does not threaten human health.”

During a recent call, Sue told me she found two dead hawks that “seem to have just fallen out of the sky.” She can’t prove pollution from the fracking industry killed the birds, but she doesn’t think the connection requires much of a stretch. A nature lover and eight-year-resident of West Texas, she worries about all the creatures she shares the desert with, including the Texas horned lizard (also known as horny toads) and roadrunners, species she is seeing much less frequently.

Primexx, the operator fracking multiple sites nearest the Franklins’ property, is choosing to drill directly across the road from their home. James said putting their rigs there is a clear indication the company cares only for its own profits.

“There is no reason that the frack pad sites weren’t set up at least a few feet away, instead of directly across from the homes along this road,” he said.

Dark Skies, Wilderness, and an Encroaching Oil Industry

Fracking industry sprawl has encroached on other small towns popular with tourists in the southwest Permian Basin, an area known for rugged natural landscapes and big dark skies. Fort Davis, where stargazers flock to the McDonald Observatory, is reputed as having the best view of the Milky Way in the US, and Alpine, Texas, is considered the gateway to Big Bend National Park, where dramatic limestone cliffs, diverse desert wildlife, and ancient pictographs draw hundreds of thousands of visitors a year.

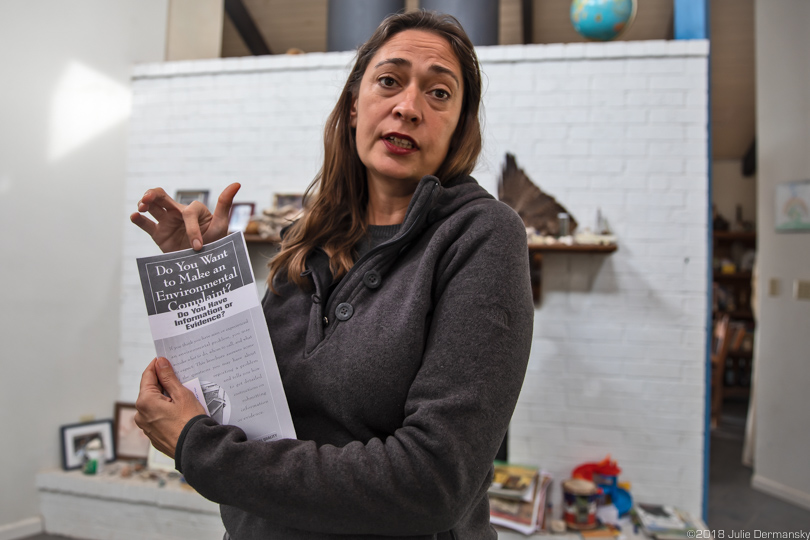

Alpine resident Lori Glover, who works part time for Earthworks, an environmental advocacy group, has been monitoring fracking industry sites in the region and helping residents like the Franklins file environmental complaints with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ).

Lori and her husband Mark are both environmental activists who helped lead the fight against Energy Transfer Partners’ (now Energy Transfer’s) Trans-Pecos pipeline, which was built to transport fracked gas from West Texas to Mexico. Though their efforts weren’t successful in preventing the pipeline’s construction, they believe the resistance against the pipeline helped raise awareness of the fossil fuel industry’s impacts on the region.

They ran a protest camp on land they own, and both were arrested while trying to stop construction of the pipeline.

“We risked everything — home, income, friends, marriage — to fight off the oil and gas industry and preserve the sanctity of the Big Bend,” Lori said. Big Bend National Park is about 80 miles south of Alpine and is a place Mark describes as the last pristine frontier in Texas.

The Glovers, like the Franklins, didn’t think Alpine, about 60 miles southeast of Balmorhea, would be affected by the oil and gas industry when the couple put down roots there together about 13 years ago. But they told me the air quality today is noticeably different. Smog now interferes with their view of the surrounding mountain range and has taken a toll on the family’s health. They say at least one of them has a cough at any given time.

I told the Glovers I smelled gas when I stopped to photograph an anti-Trans-Pecos pipeline sign about a quarter mile from their house. That didn’t surprise them. Mark had already called in a complaint for what he figures is a natural gas leak from a nearby transmission pipeline. He said he would call it in again but doubted it would make a difference.

As for regulators, the “TCEQ is AWOL in the Permian,” Mark said during a chat at the Glovers’ house, which sits at the base of the Sunny Glen Mountains.

Not once since Lori started monitoring air pollution in the Permian Basin for Earthworks just under a year ago has she not found something out of kilter, from methane flares burning black smoke to the sickening and dangerous smell of hydrogen sulfide.

Whenever possible she files a pollution complaint but often she can’t specify the exact location of potential violations because they often are not accessible from a public road. This makes it impossible to identify the site operator, making it impossible to file a complaint.

The Glovers have considered moving away but think it is important to challenge the oil and gas industry: If not them, then who?

The Franklins have considered moving too. James told me he’d be willing to clear out if he can manage to sell his house for what he feels it is worth, but Sue wonders what good moving will do.

“Where can you go where humans aren’t in the process of destroying the planet?” she mused.

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser to raise $41,000 in the next 7 days. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.