Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

“Somehow the watercourse is to dry country what the face is to human beauty. Mutilate it and the whole is gone.”—Aldo Leopold, Conservationist in Mexico, 1937

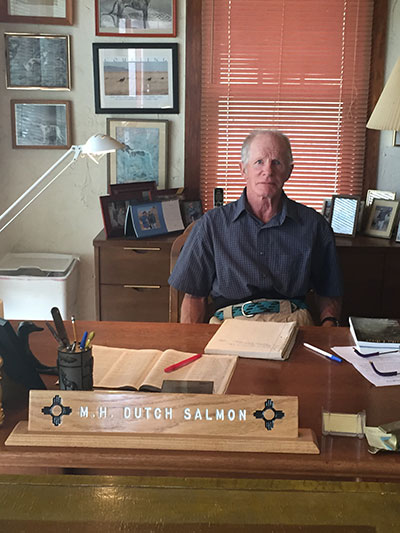

“… these subsidized water projects, they’re not really intended to serve growth, or to meet growth, they’re intended to create it.”—interview with M.H. “Dutch” Salmon, author of ¡Gila Libre!, August 2015

New Mexico’s Gila is not a big river. At least, once it has left the state, along its lower reaches, it’s not a big river anymore: Once it wends its dammed and diverted way through Arizona, it becomes a dry, sandy-bottomed reminder of a once living, powerful water course several miles wide – the epicenter of human cultures stretching back millennia. But now a new threat, closer to its source in New Mexico, has returned.

Mayor of Silver City Mike Morones. (Photo: Chris Williams)For the fourth time in as many decades, the last wild-running river in the state is threatened by the re-emergence of a giant river diversion and water storage plan. Despite intense and growing local opposition, that plan took an ominous step forward on November 23. On that day, the US Department of the Interior signed an agreement with the Central Arizona Project Entity to study options to further evaluate potential water projects related to the Gila River, one of which is the proposed diversion and storage plan. The proposed diversion project, if enacted, will radically alter the flows and pathway of New Mexico’s Gila River, threatening its rich ecological tapestry.

Mayor of Silver City Mike Morones. (Photo: Chris Williams)For the fourth time in as many decades, the last wild-running river in the state is threatened by the re-emergence of a giant river diversion and water storage plan. Despite intense and growing local opposition, that plan took an ominous step forward on November 23. On that day, the US Department of the Interior signed an agreement with the Central Arizona Project Entity to study options to further evaluate potential water projects related to the Gila River, one of which is the proposed diversion and storage plan. The proposed diversion project, if enacted, will radically alter the flows and pathway of New Mexico’s Gila River, threatening its rich ecological tapestry.

Resources for Empire: The Gila in Historical Context

Nightime over the floodplain of the Gila, stupendous natural beauty. (Photo: Chris Williams)

Nightime over the floodplain of the Gila, stupendous natural beauty. (Photo: Chris Williams)

While the Gila may not be a large river, the fight to preserve the wildness of the Gila has intense symbolic, historical, cultural and contemporary meaning. It raises a socio-ecological question of far wider significance: How should we approach and treat the natural world and see our relationship within it? When deciding on such a giant infrastructural project, with whom should the final decision rest?

As it turns out, a large part of the reason why the Gila remains free running and “wild” has to do with how it was shaped by Native American resistance to the plans of colonial invaders – a point made by Edwin Corle, who insultingly remarked in his 1951 book The Gila: River of the Southwest that “The Apaches had successfully retarded white civilization from the days of Coronado up to the campaign of General Crook” in the 1880s.

Despite the recent undamming of some rivers, which has occurred as the negative environmental and social consequences of dams have become more apparent, the current proposal hearkens back to that post-Civil War era, when the reunified United States fully re-engaged in conquering Native American lands, viewing nature as “resources for empire.” Writing in 1889, irrigation expert Frank Nimmo Jr. said, “Upon us rests the obligation of the Divine mandate – ‘Subdue the Earth.'”

For “mighty empire” builders such as Nimmo, the forcible rearrangement of rivers and recontouring of arid areas was “the last and perhaps most important chapter in the history of the subjugation of wild lands to the uses of civilized man upon this continent,” according to Donald Worster’s Rivers of Empire: Water, Aridity, and Growth of the American West.

Though the Gila may not be sizeable by comparison with other great rivers of North America, its free-running path is redolent with a spirit of resistance that echoes through the ravines and gullies, reverberating across the stands of cottonwoods, coyote willow, alligator juniper, alder, oak, Arizona sycamore and ponderosa pine that line the river.

High up in the ice caves of the Mogollon Range of New Mexico, the Gila begins its 600-mile journey to the Colorado River. Crashing through steep-walled canyons, swirling tempestuously around ancient desert rocks, the Gila in full flood is a tumultuous, roaring cascade of wild, ferocious energy, tearing its way toward the lush valley below, its catchment area bringing life to tens of thousands of square miles.

Gila Ecology

Sunrise over the upper Gila. (Photo: Chris Williams)

Sunrise over the upper Gila. (Photo: Chris Williams)

According to biologist Martha Cooper, New Mexico program director for the Nature Conservancy, there is a wider ecological and scientific importance to keeping the Gila the way it is, because “an intact, functional river is a reference river for all the other projects that have started in the West, to dismantle dams and repair rivers.” According to Cooper, it’s important that we “learn from ‘natural infrastructure,'” instead of demolishing it.

As outlined in the Nature Conservancy’s detailed report on the Gila, the river is unique in the variability of its natural flow: The river goes through radical changes in depth and size over the course of a year. This variation in flow is an essential component to a locally flourishing biodiversity. The highly fertile floodplain that surrounds it is dependent on regular inundations of nutrient-rich sediment, the replenishment of groundwater sources and the relative absence of dangerous flooding.

These highly mutable seasonal flows support a rich array of plants, animals, invertebrates and fish. Two endangered fish species live in the river: spikedace and loach minnow, and any storage or diversion would not only threaten the last remaining intact native fish populations in the Colorado River Basin, but also reduce the numbers of insects crucial to the health of the entire ecosystem while compromising the availability of water for the cottonwoods and willows.

Any diversion project is particularly problematic because of the legal arrangements of the interstate water-sharing program, the New Mexico Consumptive Use and Forbearance Agreement (CUFA), ratified by the Arizona Water Settlements Act in 2004, which modified the terms of the Colorado River Basin Project Act of 1968. CUFA withdrawal allotments for New Mexico mean that water levels in the Gila would generally only be sufficient for legal water extraction during months of peak flow.

Hence, water could likely only be withdrawn during spring snowmelt, precisely the time when fish are spawning and life regenerates after the cold winter months. Once climate change is layered on to imminent transformations in the Southwest’s desert region, where regional flows of water are already at historical lows for the 20th century, the threat to this lush ecological area further intensifies, making the possibility of wringing water from the Gila at any time of the year a dubious proposition.

Once the three branches of the Gila meet, it becomes navigable by kayak and canoe; only non-motorized craft are legally able to traverse the headwaters. The restriction is a result of the river emerging in the first-ever designated wilderness area of the United States, a tribute to the work of famed environmentalist and scientist Aldo Leopold, author of A Sand County Almanac, in the early 1900s.

In a 1921 article in the Journal of Forestry, Leopold argued for “selecting such an area as the headwaters of the Gila River on the Gila National Forest” to be conserved as wilderness – a place where industrialized logging, roads and buildings would be barred. His essay led to the establishment of the first official wilderness area in the United States in 1924, when 655,000 acres of the Gila National Forest was set aside as wilderness, a prelude to one of the most far-reaching pieces of federal conservation legislation, with the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964.

People have lived in the mountainous riparian region that surrounds the two rivers for several thousand years. Beginning a thousand years ago, the Mimbres people built permanent villages in the area and painted images of local wildlife and geometric patterns on their beautiful pottery.

Images of Tlaloc, the Aztec deity associated with water, rain, lightning and fertility, features heavily in Mimbres designs, which show the importance of a fluctuating but nevertheless reliable flow of water, and its control through irrigation works, as illustrated by the many depictions of composite figures of humans and fish, frogs or turtles on their pottery. The rich floodplain of the Mimbres and Gila rivers, still farmed by small collectives of irrigators, remains a green oasis in an arid region.

The Plan to Divert the Gila

The Free Flowing Gila River on its way to Arizona. (Photo: Chris Williams)

The Free Flowing Gila River on its way to Arizona. (Photo: Chris Williams)

The expensive water diversion and storage plan, concocted by engineers and state planners in New Mexico’s Interstate Stream Commission (ISC), stands in opposition to the Mimbres’ view of the natural and human worlds as one interconnected whole. Though 45 different proposals for use of the tens of millions of dollars in federal funds made available by the 2004 Settlement Act were submitted to the ISC, only one was approved with adequate funding for serious consideration: their own – the largest, most unwieldy and ecologically damaging one, which would necessitate nine-tenths of the funding miraculously materializing from elsewhere.

For local New Mexico author and veteran activist M.H. “Dutch” Salmon, who helped to successfully fight all three of the previous river diversion plans, stretching back into the 1970s, the importance of the campaign to prevent this new diversion project cannot be overstated. “If you can’t save a place like the Gila, you can’t save anything,” Salmon said. “We’re all doomed in the end to lose those kinds of places. But if we can save the Gila, it speaks well for the future. It says we can set aside some places that you just can’t muck around with, and you can go there and enjoy it, but you can’t change it. And … so that’s what I’m hoping. [This] can serve as an example of what we can accomplish.”

Indeed, in 2014, the organization American Rivers listed the Gila as one of the most endangered rivers in the United States.

According to the federal government’s own analysis, the diversion project proposed by the New Mexico ISC would cost a staggering $750 million. Other estimates from the previous head of the ISC, Norm Gaume, a water expert and fierce opponent of the project, put the cost at over $1 billion. For taxpayers in rural southwestern New Mexico, in the small towns of Deming and Silver City, these expenditures make any water that might come from a diversion economically preposterous.

Not only is the project economically unfeasible, according to Gaume and several other independent reports, but it is completely unworkable: The proposed site has a rock wall on only one bank of the river, a river which regularly changes course across the floodplain, and there is only a single-track dirt road to provide access to the hulking construction trucks and equipment that would be necessary to build the diversion and seal the valleys to store the water the ISC wants to extract. The Gila is an alluvial river system, meaning that it consists of fine particles of loose soil and sediment washed from higher altitudes to create a fertile floodplain. Therefore, each year the river can change course, which enhances the fertility of the surrounding land, as different areas are flooded with fresh nutrients. Soils are moistened, and insects return and are food for birds, fish, reptiles and mammals.

The US Bureau of Reclamation’s 404-page appraisal report, released in 2014, which examines possible diversion projects, states conclusively that the “cost and benefit analyses indicate the costs exceed benefits for all of the diversion proposals and the other diversion and storage options.” Furthermore, while there were some short-term employment opportunities, “the long-term impacts of the proposed projects would be very small relative to the overall economy.”

Local Resistance

The steep winding Dirt Track that would have to be radically upgraded to being construction. (Photo: Chris Williams)

The steep winding Dirt Track that would have to be radically upgraded to being construction. (Photo: Chris Williams)

Hence, the project is neither economical now, nor in the future. In an interview with Truthout, Mike Morones, the two-term mayor of Silver City, and a vocal opponent of the diversion plan, concurred:

It’s short-term jobs. Most of the high-level positions and profits would be leaked outside our community, so it’s … major dollars going outside of our community. And yes, during the process, there would be some lower-level, short-term jobs, and we might get a decent little spike in our economy in that period of time. But that’s nothing – that’s not the type of economic development I rely upon, and generally, Silver City doesn’t rely upon.

Small-scale infrastructure projects are not only more ecologically sustainable, but also are better for the local economy, “allowing dollars to circulate in state and in our general area,” Morones added.

In part, it would be Morones’ constituents who would be paying for the diversion and whatever water is captured. Having studied the proposal in detail, Morones is adamant that the diversion is unnecessary and far too costly to be viable:

We clearly don’t need it, and we don’t even feel that the county needs it, per se. We’re very secure, and if we were to work on our regional plan and our groundwater plans, we don’t see why the entire county can’t be served with water … It’s one of the most expensive, per-gallon, projects I’ve ever heard of.

The wider historical implications – in terms of the culture and memories of displaced Native Americans – are similarly extreme. Examining the possible impact on Native American history, the 2014 Bureau of Reclamation report notes that:

There are few archaeological or cultural resource surveys completed within the proposed project areas. However, based on archaeological site densities in other parts of the desert southwest, and especially in New Mexico and along riparian areas, it is very likely that there would be a high density of archeological sites.

Indeed, the middle fork of the Gila is the area where Geronimo, leader of the last armed Apache resistance, was born. Geronimo himself remembers his childhood around the Gila, according to an interview quoted by David Roberts in Once They Moved Like the Wind: Cochise, Geronimo, and the Apache Wars: “sometimes we played at hide-and-seek among the rocks and pines; sometimes we loitered in the shade of the cottonwood trees or sought the shaddock [a kind of wild cherry] while our parents worked in the field.”

The fact that the Aldo Leopold Wilderness and Gila Wilderness areas have not been degraded by white settlers looking for land and minerals can be attributed directly to Apache resistance. Continuing without pause for 36 years, the Apache resistance on US soil in the southwest is the longest military counterinsurgency in US history. Officially starting in 1850, organized resistance was not suppressed until 1886, with the final surrender of Geronimo and his remaining band of 38 Apache. Sporadic confrontations continued into the 20th century. Apache endurance represented undying resistance to colonial oppression that continues to this day.

Petroglyphs on the banks of the Gila River stand as a reminder of the many Native American cultural sites located in this region. (Photo: Chris Williams)

Petroglyphs on the banks of the Gila River stand as a reminder of the many Native American cultural sites located in this region. (Photo: Chris Williams)

Mayor Morones is not unaware of the history or the short-termism of any decision to implement the project. “One of the things I struggle with the most is, is it just simply shortsighted?” he said. “From a historical standpoint, yes, the first national forest and the first national designated wilderness being undermined by this project, historically doesn’t sit real well. Culturally, you wouldn’t think it would sit real well.”

Morones added, “I think of all those millions of dollars and I think of the tens of thousands of acre-feet [of water rights] that are owned in the Mangas Trench by corporate America. The most obvious is – I don’t know what [the mining giant] Freeport owns … Well, you tend to think – or I, in my simple mind – what would it cost to buy 14,000 feet in the Mangas Trench that’s there and secure and available, and develop smarter groundwater infrastructure and use it from that direction?”

Grant County Planning Director Anthony Gutierrez. (Photo: Chris Williams)A Diversion Proponent

Grant County Planning Director Anthony Gutierrez. (Photo: Chris Williams)A Diversion Proponent

On the other side of the fence sits county planner Anthony Gutierrez, planning director for Grant County, who is responsible for oversight for water issues at the county level. Gutierrez says he believes that a small, non-intrusive project would be beneficial (though, of course, that’s not the one that is proposed by the ISC and on the table for potential implementation).

In speaking with Truthout, Gutierrez disputed Morones’ point about the area having enough water. “We have well-drillers in the area that I speak to pretty consistently, that say wells are going dry all over the place,” Gutierrez said. “So we’re losing a substantial amount of groundwater.”

He noted: “We’re getting absolutely no recharge. It hasn’t snowed here in probably seven to 10 years. I mean, it snows, but it doesn’t get a substantial snowpack. So now we’re seeing all of those groundwaters being depleted, especially in the Luna County area, where they have substantial, a lot more agriculture in the area, huge chili farmers, cotton, alfalfa, corn.”

Gutierrez said he was contemplating and planning not for the next 10 years, but the next 50. He projects increases in both population and water use. Hence, for opposite reasons, his point is in alignment with Salmon’s analysis: The infrastructure is predicated on future increases in usage. Yet, where the water to be extracted will come from is highly uncertain. Gutierrez himself said that without snow, one cannot have water in the West:

I’m not a hydrologist, so, I mean, yeah, I read the reports, and some of it I understand; some of it I don’t, but the fact is, I can’t agree with the fact that we’re not getting any recharge for our aquifer and we’re not gonna have a deficiency of water. It doesn’t make any sense to me. Doesn’t make any more sense than the Colorado and the significant decrease in snowpack in Colorado, and now the deficiency they’re having in Arizona, Nevada and California. Of course that’s a much larger scale, but it works the same. If you don’t have snow, you don’t have water.

On November 23, the Department of the Interior signed an agreement with the New Mexico Central Arizona Project Entity to further evaluate a Gila River water project. As Jennifer Gimbel, principal deputy assistant secretary of the interior for water and science, stated in a press release, such an evaluation will ensure “that a robust review process will be completed under the National Environmental Policy Act, the Endangered Species Act, the National Historic Preservation Act, and other environmental laws before a final decision is made. This review process will include early development of a full-range of alternatives to meet water supply needs in southwestern New Mexico, which will inform the CAP Entity, Interior, and the public as analysis proceeds and will provide ample opportunities for public participation.” If Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell is genuinely committed to a thorough and transparent review of the Gila diversion project as stipulated in this agreement, to determine the project’s suitability across a range of factors, then surely this boondoggle will be terminated.

Nevertheless, despite making absolutely no sense from an economic, ecological, historical, cultural or social perspective, the danger is that – in the name of a myopic adherence to outmoded ways of thinking about our relationship to nature and the potential for profit – the diversion might be pushed through by the state-level arbiter of power on water development issues, the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission.

Gutierrez, a self-professed lover of the Gila, nevertheless bemoaned the fact that currently, trees use up a lot of water in the area:

I don’t know if you walked down the riverbed or anything like that, but a lot of it has huge amounts of vegetative growth now. Each one of those trees, could you imagine how much water it takes out of the – if you could actually do a study on how much – I think a cottonwood, a full-grown cottonwood takes out like 600 gallons a day … all that vegetative growth, I mean, it is just thick. You can’t hardly walk around; you can’t – it’s a jungle … okay, the natural flow of the river, the natural regime of the river is to allow that vegetative growth. Okay, fine. But they use up a lot, a lot of water. A lot of water.

I spent four awe-inspiring days kayaking down the Gila, marveling at the serene beauty of the region. I’m sure that the mighty cottonwoods, some of which are perhaps still standing from when Geronimo played beneath them, do drink a lot of water. Yet, surely that’s the point. We know these “wild” places have already been shaped by a variety of human societies, just not societies as voracious and shortsighted as the current capitalist regime, which is still hell-bent on acquiring “resources for empire.”

Hence, the tireless activists at the heart of the Gila defense campaign must remain vigilant organizers and expand and deepen their campaign. All those who support their aim of preserving the vibrantly free-running Gila for future generations can register their support here.

To quote Hakim Bellamy, inaugural poet laureate of Albuquerque, from his “Everywhere Is a Gila”:

A billion dollars deported

a runoff of our resources

Evaporating the forest

New Mexico can’t afford it

First they walled the border

Now they wallin’ the water

¡Gila Libre!

Wild sunflowers proliferate along the banks of the river a sign of the biodiverse ecosystem. (Photo: Chris Williams)

Wild sunflowers proliferate along the banks of the river a sign of the biodiverse ecosystem. (Photo: Chris Williams)

Trump is silencing political dissent. We appeal for your support.

Progressive nonprofits are the latest target caught in Trump’s crosshairs. With the aim of eliminating political opposition, Trump and his sycophants are working to curb government funding, constrain private foundations, and even cut tax-exempt status from organizations he dislikes.

We’re concerned, because Truthout is not immune to such bad-faith attacks.

We can only resist Trump’s attacks by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

Truthout has launched a fundraiser, and we have only 24 hours left to raise $17,000. Please take a meaningful action in the fight against authoritarianism: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.