Scientific and technological innovations have the power to fundamentally transform human civilization as new possibilities previously deemed impossible are made realities. However, it is not the technologies themselves that dictate the nature of the political, economic or social evolution. Rather, it is control over, and access to, technology that has the truly profound impact. While advanced medicines, new methods of energy production and biotechnology breakthroughs are in themselves important, when monopolized by a select few, the implications for the majority of people can be dire.

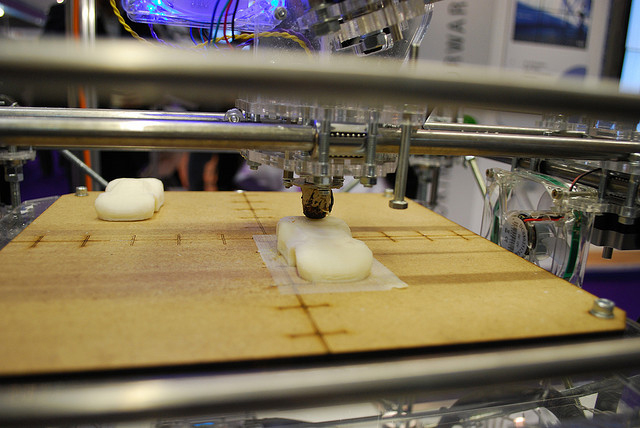

So it is with the emerging revolution in 3D printing, a technology that manufactures (or “prints”), layer by layer, physical objects from computer models using a variety of materials. While 3D printing has existed in concept since the early 1980s, only in recent years has the technology been brought to the desktop level, allowing individuals and small groups of hobbyists to print a wide variety of objects, from plastic coasters to medical equipment. Having started in the traditional industrial and fabrication setting, it was the application of 3D printing by independent, technologically inclined “hackers” (individuals who manipulate and/or customize computer and electronic equipment to fit their needs) that helped mainstream this technology.

The central question will be whether or not the ability to 3D print the elemental parts of modern and future society will be open to all, or controlled by the few.

Today, there is a consensus among those in the know – from the most ruthless capitalist profit-seekers to anarcho-communist hackers – that the 3D printing revolution is coming, and the world will not be the same once it arrives. So the struggle is not whether there will be 3D printers, but rather how that technology will be used, how it will be dispersed in society, who will have access to it, and who will control and/or steer its development.

The central question will not be whether a working-class person can 3D print some household object in his garage; this is a foregone conclusion. Instead, it will be whether or not the ability to 3D print the elemental parts of modern and future society (computer processors, nanobots, telecommunications equipment etc.) will be open to all, or controlled by the few.

And it is here, on the front lines of the battle for control and access to this breakthrough technology, that the struggle between the political and economic establishment and the rest of us is taking place. On the one hand, there are those tirelessly working to democratize and decentralize 3D printing, and on the other hand are the powerful forces that seek to monopolize this innovation in order to maintain their grip on power.

3D Printing, Decentralization and the DIY Revolution

As 3D printing gradually moved out of the realm of science fiction to become a technology that could be financially and technically accessible to individuals, the transformative potential of the innovation became readily apparent. Obscure startups such as New York City-based MakerBot brought 3D printing to the desktop via the NYC Resistor hackerspace – a “hacker collective” based in Brooklyn where communally owned tools and computers bring together a wide array of innovative technology enthusiasts who share knowledge and expertise in a variety of fields. Such a combination of technical know-how and ideological commitment to collaboration has fueled the creative energies of many such hackerspaces and makerspaces, and the many politically conscious, often radical activists and non-activists alike, to generate wildly fascinating and innovative breakthroughs.

And it is within these hacker and makerspaces where 3D printing really began to take off. No longer were 3D printers large, unwieldy machines only to be understood and used by a select few with deep technical knowledge. Rather, they became accessible, moving toward a fully decentralized model wherein designs could be shared freely on open-source platforms, where new models could be created that would make the organic development of the technology inevitable. 3D printers such as RepRap – a free desktop 3D printer capable of printing plastic objects in order to replicate itself – assure the proliferation and continued evolution of the technology.

3D printing has the potential to do for manufacturing what RSS feeds (and the internet as a whole) did for information.

More importantly, these sorts of innovative designs cannot be easily controlled or stifled, as there is no individual or group that can monopolize them. They are free and open to all who are willing to experiment with them. In this way, 3D printing has the potential to do for manufacturing what RSS feeds (and the internet as a whole, in the broadest sense) did for information – exponentially increase the potential for individuals and communities to organize it, and to make it freely accessible to all.

Imagine the implications of a small group of individuals with 3D printers being able to manufacture the rudimentary parts necessary for electronic gadgets for their friends who would otherwise have to go to some corporate retailer to buy them. Likewise, consider the social impact of large-scale 3D printers capable of printing affordable and sustainable housing (such as those demonstrated by the Chinese company WinSun) being owned by local communities. The implications are staggering as complex social issues such as underdevelopment, homelessness, unemployment and many others might be, at least partially, addressed through the integration of such technology.

However, the technology is not without its adverse effects in the near term. As Anne Elizabeth Moore incisively explained in Truthout in 2013, the incorporation of 3D printing into the garment industry would quite likely endanger the jobs of millions of workers in the global South, the majority of whom are women. Indeed, the more 3D printing technology is integrated into the industry, the less need there would be for millions of garment factory jobs in Bangladesh, Cambodia and elsewhere – a dangerous development for an already marginalized segment of the global labor pool.

That said, it is the corporations and neoliberal ideologues that seek to incorporate 3D printing into a global capitalist system in which profits, rather than increased living standards and improved quality of life, are the ultimate goal. For others, especially those in the maker/DIY movement, the goal is to leverage technology to transform an exploitative corporate system into something altogether new. Rather than simply defending low-wage employment, the objective is to take the means of production out of the hands of those with capital, and put them into the hands of the workers themselves. It is not the middle-management bureaucrat in Dhaka who performs the labor required to produce the goods; it is the woman supporting her children with her hands. It is not the peasant community on the outskirts of Phnom Penh that truly benefits from increased profits for H&M or Zara; it is the CEOs and boards of directors in the developed world.

“If you grow a piece of celery in red water, it’s going to be red … I’m just wondering how this Darpa defense contract money is going to influence these projects.”

It is undeniably true that 3D printers could pose a threat to jobs, as they exist today. However, it is equally true that they could provide a means by which the very nature of production is irrevocably altered. Those who rail against globalization and the excesses and exploitation of the “global market” would do well to consider the implications of a technology that could eliminate the dependence of much of the world on transnational corporations for many of their basic needs as local communities would increasingly have the means to produce the goods and services they require.

Moreover, the new technology would necessarily bring with it a need for more technical skills, thereby providing the impetus for expanding advanced technical education to women who, as Moore quite rightly points out, are systematically excluded from it. Additionally, the increased level of proficiency with such machines would naturally then be applied far beyond just clothing and other consumer industries: It would provide workers with previously limited employment opportunities a vastly greater horizon of possibilities.

The impact of such innovations is quite literally immeasurable. It would radically alter the very mechanics of capitalism and the political economy of the modern world, to say nothing of the transformative impact it would have on local communities and the relationship between them and the government and corporations. Who needs Walmart if you can manufacture your own consumer items? The answer is self-evident.

And so, it is equally self-evident why the corporate elites and their military-industrial-intelligence-security complex would want to stifle this technology, which they quite rightly see as an existential threat to their own power. But how are they trying to achieve this? Quite frankly, in the same way they attempt to do so with the internet – compare truly open social platforms (such as RSS) and closed platforms such as Facebook, which control and stifle the way we communicate, forcing everyone to go through the intermediary of the host and its closed architecture – by buying it up and controlling it.

The CIA, In-Q-Tel and the Suppression of the 3D Revolution?

While many have heralded 3D printing as a breakthrough technology, few seem to have grasped the true implications of how it could change the world, especially as the printing technology becomes more advanced and capable of printing more than just plastic consumer goods. However, there are many savvy investors who, combining vision and deep pockets, are getting in on the revolution on the ground floor. For them, 3D printing is merely a transformation of the means of production, a way of reducing costs while increasing profits. Such investors and venture capitalists take no heed of the millions of aforementioned workers who would lose their means of survival, as they are uninterested in the socially and economically transformative potential of the technology. They see the change not as one to society and the global economy, but merely as a slight alteration to their business models.

But there are other investors who do see the potential inherent in the development of 3D printing. One of the most provocative (and possibly worrying) investors in 3D printing is the US intelligence community.

In March 2015, it was reported that In-Q-Tel, the venture capital firm openly acknowledged as an arm of the CIA, would be investing an undisclosed amount (likely a very large sum) into a little-known 3D printing company called Voxel8, which has developed “the world’s first 3D electronics printer.” As Voxel8 founder and Harvard professor Jennifer Lewis noted, “Multi-material 3D printing holds the promise of the mass customization of electronics and the ability to truly print your imagination.” Indeed, the technology would completely transform not just the 3D printing landscape, but the entire manufacturing model when it comes to electronics.

Voxel8’s commitment is to raking in massive profits in the mass market, not to the spirit of decentralization and democratization of technology.

The CIA, through its private sector intermediary In-Q-Tel agrees. As Megan Anderson, vice president of field deployable technologies at In-Q-Tel, stated: “We are pleased to be partnering with Voxel8 to further develop its multi-material 3D printing technology … The customization enabled by Voxel8’s technology allows users to quickly create new devices without the inconvenience of tooling, inventory, and supply chains associated with traditional manufacturing methods.” Obviously, the intelligence community is excited about the possibilities that such technology brings. However, the CIA is not in the business of making charitable donations; Langley obviously sees in Voxel8 the future of 3D printing, and wants to make itself into an indispensable partner in the venture. Naturally, the CIA has its own motives.

And of course there are many within the 3D printing and hackerspace community who have raised the alarm about the co-optation, or infiltration (depending on perspective), of the hacker/maker movement generally by the intelligence community and military-industrial complex. Speaking about the infusion of funding from the notorious Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa) at a conference in 2012, Sean Auriti of Brooklyn-based Alpha One Labs incisively noted, “If you grow a piece of celery in red water, it’s going to be red … I’m just wondering how this Darpa defense contract money is going to influence these projects.” Auriti is not alone of course, as many in the community have raised similar concerns.

However, one person who does not seem to be concerned about the influence of the defense and intelligence community is Daniel Oliver, co-founder of Voxel8. When asked in a phone interview with Truthout about precisely this issue, he explained, “I don’t have any concerns about it [the In-Q-Tel investment in Voxel8] … The intelligence community does not dictate to us how to develop the technology. They view us as partners.”

The CIA, through its In-Q-Tel intermediary, is seeking to guide the development of the cutting-edge 3D printing technology in order to control it.

While Oliver, a Harvard Business School graduate, claims that Voxel8 “loves the open-source movement” and are “strong supporters of it,” he readily admits that the company will not provide its own designs freely to the public, laughing off the notion that seeking profit could possibly be incongruent with the goals of the open-source, DIY movement. He explained that from Voxel8’s perspective, “the two are not mutually exclusive.”

However, the profits that lie at the heart of the Voxel8 mission are evidenced by the other recent major investment in the company, this one made by well-known venture capital firm Braemar Energy Ventures. While the total investment is undisclosed, it is quite likely to be substantial given Braemar’s track record with many of the other companies in its portfolio. It seems that Braemar’s deep ties to companies working in oil, gas and coal industries did not present any ethical or moral obstacle for Voxel8.

Lewis, Voxel8’s founder, notes in the company’s press kit, “I am excited to leverage over a decade of research to transform the way devices are manufactured … Through the support of investors like Braemar, we are able to bring our ground-breaking technology to the mass market.” Clearly, despite Oliver and Lewis’ lip service to the open-source movement, Voxel8’s commitment is to raking in massive profits in the mass market, not to the spirit of decentralization and democratization of technology.

However, one need not crucify profit-driven entrepreneurs for seeking to make money, even if it is at odds with what many would argue is the essence of the open-source, DIY movement that birthed this technology. Where one might need more skepticism is in Oliver’s notion that partnership with the intelligence community does not mean a loss of independence in the development of the technology. As Greg Pepus, a former senior director at In-Q-Tel, explained in a 2004 interview:

When we identify a company, we enter into a venture-type relationship with them, which means there is an investment component. [We want to contribute to a] commercially viable activity that’s beneficial to the company and adds some things that In-Q-Tel would like to see in the product. And it’s a way for us to work more closely with the company to help guide its whole product strategy … We invest so we get a seat at the table with those companies early. We have a board observer position, and we are able to influence where it goes with its product.

It is almost self-evident that the CIA, through its In-Q-Tel intermediary, is seeking to guide the development of the cutting-edge 3D printing technology in order to control it, either directly or indirectly. Leverage, financial or otherwise, is one of the principal means by which the intelligence community projects its power. So, how long will it be before In-Q-Tel and the CIA have all the leverage they need over Voxel8 and the next wave of 3D printing?

As former director of the CIA David Petraeus remarked at the In-Q-Tel CEO Summit in March 2012, “Our partnership with In-Q-Tel is essential to helping identify and deliver groundbreaking technologies with mission-critical applications to the CIA and to our partner agencies.” Petraeus here clearly states what has long been known by many in the intelligence community, that the so-called private venture capital firm is little more than an arm of the CIA, which invests only in technologies that will prove useful to the military-intelligence apparatus.

Of course, decentralization, democratization and open-source technology are not useful to the CIA’s ultimate mission.

The Revolution Will Not Be Capitalized

There are some in the 3D printing community, and the broader DIY movement, who believe that the co-optation of their movement is inevitable as In-Q-Tel and others flock to it like vultures. Perhaps there is good reason to think so. On the other hand, it is the spirit of rebellion, and resistance to the establishment, which provided the initial impetus for the movement. And that spark still exists.

As Karin Kosina of the Metalab hackerspace in Austria succinctly exclaimed in 2009, “Stop being a consumer! Start to be a creator!”

While Voxel8 cozies up to the CIA, MakerBot has become a disappointment to many open-source activists since its high-profile sale to Stratasys in 2013; many in the 3D printing community view MakerBot as having become a mediocre manufacturer since the sale. But that hasn’t stopped independent alternatives from creating better, cheaper printers.

So too must it be with the new phase of 3D printing. There must be politically and socially conscious hackers and makers who will transform the kinds of technology Voxel8 is developing into a platform for independent development and experimentation. No matter how deeply the CIA, Darpa and others attempt to embed themselves in the movement, the transformation will take place. There will always be DIY’ers who, like Kosina, will stop being consumers, and instead become creators. For every dollar that goes into the pockets of Lewis, Oliver and their peers, there will be many more that will be irretrievably lost thanks to the commitment of dedicated activists.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.