In August, 1945, as Japan smoldered in the ruins of war, the question of what would become of the Korean peninsula after 35 years of Japanese occupation and a Soviet army advancing southward spurred the hasty selection of an artificial division along the 38th parallel drawn by two American officials as a border between US and Soviet “zones of occupation.”

That line, never intended to be permanent, hardened like stubborn mud before the newly liberated Korea ever had the chance to form an independent, unified and democratic nation. Today 38°N still marks a potentially catastrophic flashpoint between North and South Korea.

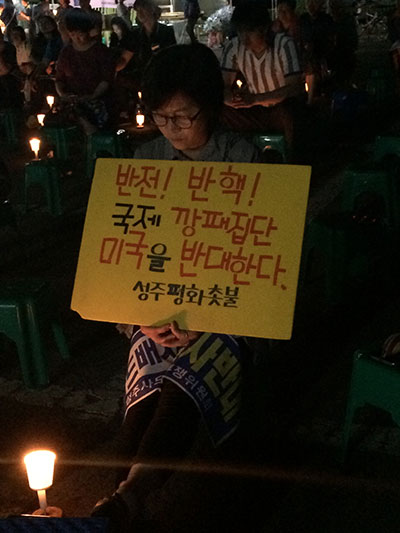

Candle light protests have been held outside the Seongju County office nightly since the deployment of the THAAD antimissile defense system was announce in July 2016. (Photo: Jon Letman)The DMZ — demilitarized zone — despite its name, is one of the most militarized places on the planet. This hyper-militarization, in fact, extends south across the peninsula and today, 64 years after an armistice halted (but never formally ended) the Korean war, South Korea remains peppered with scores of US military installations — at least 80 by the Pentagon’s own count.

Candle light protests have been held outside the Seongju County office nightly since the deployment of the THAAD antimissile defense system was announce in July 2016. (Photo: Jon Letman)The DMZ — demilitarized zone — despite its name, is one of the most militarized places on the planet. This hyper-militarization, in fact, extends south across the peninsula and today, 64 years after an armistice halted (but never formally ended) the Korean war, South Korea remains peppered with scores of US military installations — at least 80 by the Pentagon’s own count.

US bases, and the 28,500 US troops and joint military exercises they support, are not only opposed by North Korea; many South Koreans see them as a problematic construct that perpetuates the likelihood of war.

Despite frequent media coverage of North Korea’s highly choreographed military parades, increasing missile launches, and Kim Jong-un’s threats to turn Seoul into a “sea of fire,” far less attention is paid to South Korea’s tireless, well-organized peace movement opposed to militarism on both sides of the DMZ.

South Korean civil groups and NGOs like People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy and the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions are skilled at forming coalitions with peace activists and religious groups opposed to a military buildup, which they see as increasing tensions with the North and militarization across Northeast Asia.

Your Old Farm Is Our New Base

Many of the protesters against THAAD are elderly melon farmers who are upset that their mountain village is being militarized. They complain that US Army Chinook helicopters are flying over there village up to 10 times a day (and sometimes night), rattling windows and nerves. (Photo: Jon Letman)

Many of the protesters against THAAD are elderly melon farmers who are upset that their mountain village is being militarized. They complain that US Army Chinook helicopters are flying over there village up to 10 times a day (and sometimes night), rattling windows and nerves. (Photo: Jon Letman)

With the bulk of US bases concentrated in and around Seoul and within range of North Korean artillery, the US is in the middle of a major realignment of its forces as it consolidates bases, moving tens of thousands of troops, their families and civilian contractors to US Army Garrison Humphreys in the city of Pyeongtaek, 40 miles south of Seoul.

In 2002, when the US announced its plan to triple Humphreys in size, Pyeongtaek residents living around the base organized fierce protests that raged for five years. Thousands of police were deployed, citizens were arrested and villages were demolished. In the end, however, the base’s walls were pushed outward, and Camp Humphreys grew from just over 1,000 acres to more than 3,400 acres, making it the US’s largest overseas military base in the world. Now in the final years of construction, US Army Garrison Humphreys is equipped to serve as the new headquarters for the Eighth US Army and US Forces Korea command center.

A representative of the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions holds an anti-THAAD banner at a demonstration in Soseong-ri, Seongju County, South Korea. (Photo: Jon Letman)

A representative of the Korean Confederation of Trade Unions holds an anti-THAAD banner at a demonstration in Soseong-ri, Seongju County, South Korea. (Photo: Jon Letman)

The Humphreys expansion is slated for completion by 2020 and will eventually be home to up to 46,000 military and civilian personnel living and working behind razor wire-topped walls and gates. The $10.7 billion expansion, the US’s largest-ever peacetime military construction project, is being paid for overwhelmingly (around 90 percent) by the South Korean government. In 2016, Gen. Vincent Brooks (now head of US Forces Korea) publicly stated that it’s cheaper to station US troops in South Korea than in the United States.

The Humphreys expansion does have supporters in the community, and many businesses have come to depend on the US military’s presence. Pyeongtaek’s city government, unable to refuse the influx of thousands of US forces, has done its best to promote Humphreys’ expansion as an opportunity to court non-military business and infrastructure investment and push for internationalization through increased cultural exchanges with military personnel and their families.

Still, many residents view the base as an unwelcome intrusion on Korean sovereignty and a source of crime, pollution and noise from military aircraft like F-16s, A-10 Thunderbolts, Chinook and Apache helicopters.

Demonstrators march toward the former golf course in Seongju County where the controversial THAAD antimissile defense system is being deployed by the US. (Photo: Jon Letman)

Demonstrators march toward the former golf course in Seongju County where the controversial THAAD antimissile defense system is being deployed by the US. (Photo: Jon Letman)

Since 2002, Kang Song-won of the Pyeongtaek Peace Center has been working closely with residents from communities affected by Humphreys, particularly those who were forcibly relocated from the villages of Daechu-ri and Dodu-ri. Kang works with volunteers to monitor military incidents and accidents around the base. Beyond the noise and inherent danger, he told Truthout the most harmful impact of Humphreys’ expansion has been the deep divisions sown in the community between base supporters and opponents.

Giving up, however, is not an option. “Even though we lost the fight against the US military, I think it is still necessary to keep fighting … against the problems of the US military base,” Kang said.

Island of Peace, Tides of War

US Army Garrison Humphreys is a helicopter base in what will soon be the the United States’ largest overseas military base. Just beyond the fence are small farming villages. (Photo: Jon Letman)

US Army Garrison Humphreys is a helicopter base in what will soon be the the United States’ largest overseas military base. Just beyond the fence are small farming villages. (Photo: Jon Letman)

An hour’s flight south of Seoul is sub-tropical Jeju island. Home to nine UNESCO Global Geoparks and a World Heritage site, the volcanic island is renowned for its natural beauty and biodiversity both on land and sea. Jeju has also been heavily developed for tourism. On the south coast, in Gangjeong village, is the site of a new Korean naval base.

Muddying its primary purpose, the base is sometimes called the Jeju Multipurpose Port Complex and is touted as having a (future) dual civilian-military function, but for now it’s strictly a Korean naval base and headquarters for the South Korean Navy’s Mobile Task Force Flotilla-7, which includes Aegis warfare destroyers, KDX III helicopter destroyers and a submarine force command.

Like the expansion of Camp Humphreys, the 2007 announcement of the Jeju naval base sparked widespread outcry from residents opposed to the militarization of what was dubbed “Island of Peace” in recognition of Jeju’s horrific April 3 massacre (1947-54). In that massacre, as many as 30,000 island residents were killed by Korean forces over a seven-year period beginning in 1947 during the US military administration that occupied the southern part of the Korean peninsula immediately after the August 1945 defeat of Japan.

As in Pyeongtaek, Jeju base protesters clashed with the police for years. Base opponents, including the former mayor, were arrested and heavily fined but in the end, the base was built.

Many of the residents protesting against the deployment of the THAAD antimissile defense system are elderly farmers who don’t want their remote mountain village to be militarized. (Photo: Jon Letman)

Many of the residents protesting against the deployment of the THAAD antimissile defense system are elderly farmers who don’t want their remote mountain village to be militarized. (Photo: Jon Letman)

Tangerine farmers Jeong Young-hee and her husband Kang Sung-won have been growing Jeju’s famous citrus varieties for 30 years in greenhouses less than two miles from the base. Young-hee and Sung-won are concerned about the environmental impact of the base, especially the effects on the sea — including soft corals, sea urchins, abalone and other marine life — and the destruction of what was a sacred lava rock coastal field called Gureombi.

Construction on the base is not yet complete. Young-hee and Sung-won worry that as it grows, if a future exclusion zone (a zone that would restrict new construction) is declared, it would surround their farm, almost certainly driving down land values.

Peeling one of her sweet hallabong oranges, Young-hee explains how the base has caused a rift between friends and family members. The base has also divided many citrus farmers and Jeju’s famous Haenyeo free divers. “Our relationship was destroyed,” says Young-hee, who joined her male counterparts in shaving her head as a gesture of protest against the base.

In the early days of the struggle, when base opponents pointed fingers at the US accusing it of pressuring South Korea (also known as the Republic of Korea), South Korean officials denied that the base would permanently host US warships. This year, in March and June, US warships made their first visits to the Jeju base with short, inconspicuous port calls similar to what was recommended in a 2013 US Army War College strategy research project. Last January, US Pacific Command’s Adm. Harry Harris suggested the possibility of deploying the US’s newest, most lethal stealth destroyer, the USS Zumwalt to Jeju waters.

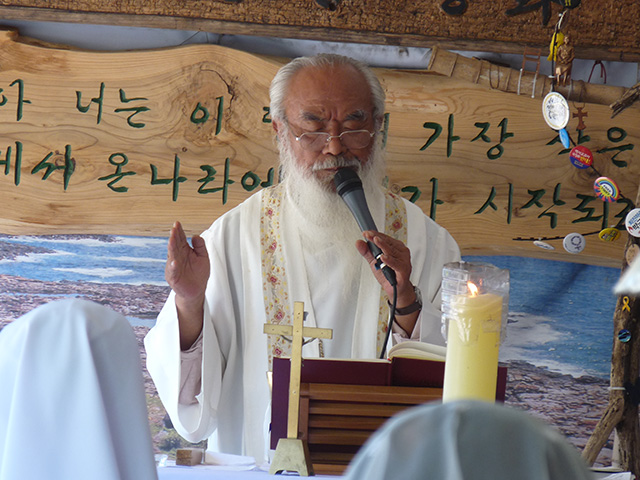

Retired Catholic priest Father Mun Jeong-hyeon holds a daily mass along along a roadside site that doubles as a protest against the Jeju naval base in Gangjeong village, Jeju island. (Photo: Jon Letman)

Retired Catholic priest Father Mun Jeong-hyeon holds a daily mass along along a roadside site that doubles as a protest against the Jeju naval base in Gangjeong village, Jeju island. (Photo: Jon Letman)

The Jeju navy base became operational in February 2016. Resistance continues daily, with activists gathering each morning in front of the entry gate to perform one hundred bows as a nonviolent, meditative protest. Nearby, in a roadside tent chapel, retired Catholic priest Father Mun Jeong-hyeon leads a daily mass, before joining protesters who gather with flags and banners playing raucous music outside the base. The mood of the protesters is defiant and the message is serious: they want a shift away from militarization of the Korean peninsula and northeast Asia.

This week (July 30-August 5), for the eighth year since 2008, a peace march is underway, in which activists are walking from the Jeju naval base around the island to raise awareness of the continuing struggle and to call for peace.

In Defense of Who?

Guards look out from behind a razor wire fence surrounded the new South Korean naval base on Jeju island, South Korea. (Photo: Jon Letman)

Guards look out from behind a razor wire fence surrounded the new South Korean naval base on Jeju island, South Korea. (Photo: Jon Letman)

South Korea’s latest struggle against militarization began in July 2016 in rural, traditionally conservative Seongju County 135 miles south of Seoul. Residents of Seongju and neighboring Gimcheon were caught off guard when the central government, under deposed President Park Geun-hye, offered Seongju to the US as a location for the US antimissile defense Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system. For more than a year since that announcement, daily protests have been taking place in Seongju and elsewhere around the country. In June, an anti-THAAD protest of several thousand people briefly and peacefully surrounded the US embassy in Seoul.

THAAD manufacturer Lockheed Martin says the system is intended to defend “US troops, allied forces, population centers and critical infrastructure against short and medium range ballistic missiles.” Seongju residents and Koreans across the country, however, recite a litany of reasons they are opposed to THAAD, from environmental and health concerns to the lack of a democratic process to ever-increasing deployment of foreign weapons, as well as economic repercussions and tension with its neighbors China and Russia.

South Korean Army personnel stand guard at the Demilitarized Zone/Joint Security Area outside the Military Armistice Commission buildings along the tense border. (Photo: Jon Letman)

South Korean Army personnel stand guard at the Demilitarized Zone/Joint Security Area outside the Military Armistice Commission buildings along the tense border. (Photo: Jon Letman)

Two weeks before South Korea’s snap election on May 9 this year, the US, citing North Korean threats, hurriedly began the deployment of THAAD in what had been a golf course outside a small village called Soseong-ri.

When South Korea’s newly elected President Moon Jae-in learned that his own Ministry of Defense had failed to notify him of the presence of an additional four THAAD launchers, Moon called for a temporary suspension of THAAD to conduct an environmental assessment. That suspension, however, is being reevaluated now as South Korea considers deploying additional launchers in response to a North Korean intercontinental ballistic missile test last week.

Like other aspects of the military alliance between the US and South Korea, THAAD is supported by some South Koreans and reviled by others. And like the communities in Gangjeong village on Jeju and Pyeongtaek near Seoul, the people of Seongju and Gimcheon are divided.

A South Korean Army officer stand guard at the Demilitarized Zone/Joint Security Area outside the Military Armistice Commission buildings along the tense border. (Photo: Jon Letman)

A South Korean Army officer stand guard at the Demilitarized Zone/Joint Security Area outside the Military Armistice Commission buildings along the tense border. (Photo: Jon Letman)

Speaking at a candlelight vigil outside the Seongju County government office on May 30, three local women were eager to share their thoughts with Americans. On this 310th day of consecutive protests, the women told Truthout they wanted their lives back the way they were before THAAD. They said their community was being torn apart — even relations between parents and children were being strained by strong disagreements over THAAD. Some of their neighbors have given up opposition to THAAD, either accepting it as unavoidable or simply focusing on other matters.

These women, however, refuse to give up and say they feel a responsibility to attend nightly demonstrations against THAAD. They also admit feeling a growing resentment toward what they see as an unequal alliance.

“We are starting to have anti-American sentiments even though we don’t hate Americans,” a woman who identified herself as Mrs. Kim said.

“To be honest, I want the US military to go home,” said a second woman, who also goes by the name Mrs. Kim, adding the English phrase, “Yankee, go home.”

The Truth Is Very Powerful

Demonstrators perform 100 bows for peace six days a week as a protest against the South Korean Jeju naval base in Gangjeong village, Jeju island. (Photo: Jon Letman)

Demonstrators perform 100 bows for peace six days a week as a protest against the South Korean Jeju naval base in Gangjeong village, Jeju island. (Photo: Jon Letman)

Even as new bases are built, old bases expanded and more weapons imported, what fuels South Korean peace movements in the face of overwhelming power?

In Seoul, Jungmin Choi who works with Durebang (My Sister’s Place), an NGO that provides counseling to foreign women working in bars and clubs near US bases, says those women are living witnesses to the impact of military bases. Choi calls the impacts of the bases “indescribably huge” and both tangible and intangible, but insists, “we believe this fight cannot be defeated … we will fight in a creative way with a long-term view.”

On the other side of the country, Jeju base opponent Choi Sung-hee says that even though the Jeju base is operational and US warships have started visiting, the protests must continue. Not only does the military know it is being watched, but protests build solidarity with other anti-base movements across South Korea and internationally, in places like Okinawa, Guam, the Philippines and Hawaii, particularly among women.

A protester is blocked by a security guard as he sits in silent protest outside the entry to the South Korean naval base on Jeju island. (Photo: Jon Letman)

A protester is blocked by a security guard as he sits in silent protest outside the entry to the South Korean naval base on Jeju island. (Photo: Jon Letman)

“That’s the role of people … we should constantly demand: we do not need arms, we do not need THAAD, we do not need more military bases,” Choi says. “If the people’s movement is strong, I think it can also influence the decisions of the South Korean president.”

Nearby, in the St. Francis Peace Center, Father Mun carves messages of peace into wooden boards after each morning’s protest. Nearly 80 years old, Father Mun has been a peace activist for decades in Pyeongtaek, on Jeju and elsewhere acting, in his words, as “a witness for truth.”

When asked why he continues to resist in the face of overwhelming power, Father Mun declared, “The truth cannot be thrown away. The truth will stand up some day. The truth is very powerful. So, I believe the truth is going to win all enemies.”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.