Will Truthout’s mission continue in 2015 and beyond? That depends on you. Make a tax-deductible donation now to sustain our work! (Photo: Cindi Hobgood)

(Photo: Cindi Hobgood)

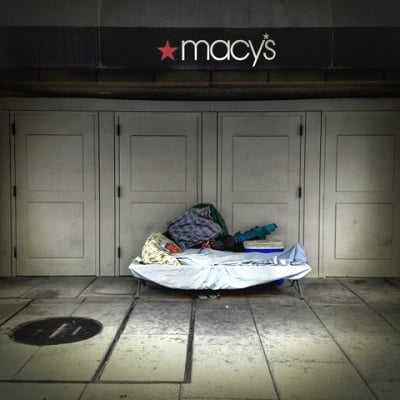

When I first began working in downtown DC two years ago, the homeless on the streets suddenly became very real to me. My previous jobs in the more affluent suburbs had ensconced me in a cocoon of sorts. Out of sight, out of mind.

But now they were so very visible – the homeless and the panhandlers (and many who were both). And I began to have an internal conversation with myself: Do I just walk by fast and ignore them? Do I put a dollar in their cups? But if I do that, I can’t do it every day. So then what?

Chances are, you too walk by them on the way to the office or when running errands. You see them with their cup out at major intersections and by the metro station. Or they may be slumped on park benches or under bridges and underpasses.

(Photo: Cindi Hobgood)Then again, perhaps not. Maybe you have stopped noticing them because they are so common they blend into the “landscape” – or because we all tend to block images that make us feel uncomfortable.

(Photo: Cindi Hobgood)Then again, perhaps not. Maybe you have stopped noticing them because they are so common they blend into the “landscape” – or because we all tend to block images that make us feel uncomfortable.

However, in light of the numbers recently reported by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, they will be hard to overlook as the cold temperatures of winter set in. The HUD report found that on the night its measurement took place, 578,424 people were homeless in America. Although that represents an 11 percent decline overall since 2007, the homeless population has continued to climb in many areas – including North Dakota (98 percent), South Dakota (53 percent), Vermont (51 percent) and DC (45.6 percent).

Great debate: Drop Money in that Cup?

According to Michael Stoops, community organizer for the National Coalition for the Homeless, “the single most frequent question we get when we speak at events is, ‘What do I do when I’m approached on the street?’ “

Some professionals in the field say unequivocally that doling out money to people who beg on the streets is not a good use of your funds – and doesn’t do much for panhandlers either.

A 2013 survey in San Francisco concluded that 82 percent were [homeless] . . . 60 percent collected less than $25 a day and 94 percent used the money for food. Fewer than half (44 percent) spent any of the money on alcohol or illicit drugs.

“The simple truth is that giving cash to panhandlers doesn’t help,” a page on the website for Montgomery County, MD, flatly states. “Those who work daily with panhandlers in homeless advocacy and other social service groups know that most panhandlers use the money they collect to support their addictions – drugs, alcohol and tobacco. None of that helps panhandlers to solve their problems.”

The website adds that despite appearances, many panhandlers are not homeless. The US Department of Justice agrees, warning that “(panhandlers’) sales pitches are usually, if not always, fraudulent in some respect.” However, at least some data contradict those negative claims. A 2013 survey of people begging for money in San Francisco concluded that 82 percent were indeed lacking a place to call home. The survey also found that 60 percent collected less than $25 a day and 94 percent used the money for food. Fewer than half (44 percent) spent any of the money on alcohol or illicit drugs.

Stoops says he typically does not give money to beggars, because “I don’t know what they will do with it.” And, as Jake Maguire from the organization 100,000 Homes observes, “no matter what you give, it won’t be enough to help in the long term.”

My own experience with giving money serves as a cautionary case in point – especially if you decide, like me, to take the time to learn a few of these stories and get “pulled in.”

The San Francisco study found that those from working-class backgrounds were more likely to give than individuals with higher incomes.

Many of the chronic homeless are like Sam and Roxanne, a couple who begs for money every morning by my Metro stop. Sam is a Vietnam veteran who has been in and out of VA programs for years, and when he is on the streets, he treats the voices in his head that urge suicide with various substances. His problems are complex and overlapping, and giving the couple money to help with one immediate need only seems to lead to another. It wasn’t long before I became their “go-to” rescuer – and not only does that exceed my budget, it also isn’t helping them change their situation. What they really need is an outreach team and case manager who won’t just tell them to come back after Sam replaces his lost ID. And even then, I wonder if they will ever trust the “system” enough to get the help that’s available.

(Photo: Cindi Hobgood)Eileen Leichter, a DC-based tax lawyer, has chosen an in-between ground. She doesn’t allow herself to get personally involved, but regularly keeps $50 in one-dollar bills in her purse to give away. It lasts a couple of weeks.

(Photo: Cindi Hobgood)Eileen Leichter, a DC-based tax lawyer, has chosen an in-between ground. She doesn’t allow herself to get personally involved, but regularly keeps $50 in one-dollar bills in her purse to give away. It lasts a couple of weeks.

“I build it into my budget,” she says. “They can get a cup of coffee with it, or match it with contributions from others and get a meal at a deli. Or, they can choose to buy booze. The way I see it, that’s not my issue. If I gave a lot more, or if our society had a better system for helping people in need, I might see it differently. But I don’t and we don’t, so I treat it as a gift. They don’t need to justify themselves to me.”

Leichter says her actions are rooted in her religious values, which inspired a tradition of giving to the humanity she saw on the streets when she first moved to Los Angeles for graduate school. “I crossed through a park on the way to classes, and would see homeless people slumped against trees just 20 feet away from Rolls Royce cars. It was such a dissonant image that I never forgot it, and I’m glad I didn’t. It’s a mystery to me how others can see that contrast every day and shut themselves off from it.”

Look, I know not everyone can or wants to give money. But at least they could acknowledge my existence with a ‘good morning’ or a smile.”

According to the Department of Justice research, the people most likely to at least occasionally give money to beggars are college students, women, tourists and conventioneers (who already are psychologically prepared to spend money), and diners or grocery shoppers (activities that remind them of their relative wealth). Interestingly enough, income isn’t a reliable predictor. For example, the San Francisco study found that those from working-class backgrounds were more likely to give than individuals with higher incomes.

Tina, one of the many panhandlers I have come to know in the course of my search for the “right” response, agrees with these findings.

Tina isn’t homeless; she rents her own apartment. She also has a job, albeit at minimum wage, at two different McDonald’s restaurants – a far cry from the cleaning service she used to own before the economic downturn began in 2008.

Her meager income, however, isn’t enough to pay the $30,000 medical bill she says she owes for her 13-year-old daughter’s heart treatment in Ecuador. Originally born in that country, Tina says she had sent her daughter to her homeland to visit her grandmother. When the girl’s health suddenly deteriorated, she required expensive emergency treatment.

“I carry items like warm socks, gloves and gift cards for McDonald’s in my brief case . . . Once a week, I give a person one of the items, along with a gentle hello. I think the human contact is as valuable as the gifts sometimes.”

Tina begs for money every day near my local Metro in between her jobs, trying to bring in a bit extra. With her medical records in one hand and a sign broadcasting her need in the other, she says she used to station herself outside office buildings where she knew higher-paid executives work. But the “suits” didn’t give much – not like the more diverse crowd that pours into the Metro station every day.

(Photo: Cindi Hobgood)“My sign was like an invisibility cloak,” she says wryly. “It was like I didn’t exist to them. Look, I know not everyone can or wants to give money. But at least they could acknowledge my existence with a ‘good morning’ or a smile.”

(Photo: Cindi Hobgood)“My sign was like an invisibility cloak,” she says wryly. “It was like I didn’t exist to them. Look, I know not everyone can or wants to give money. But at least they could acknowledge my existence with a ‘good morning’ or a smile.”

• Another Type of “Cup”: Buy a Newspaper

Whether you choose to give money of any amount to seemingly needy people on the street is a highly personal choice. There is no right or wrong answer. But if you choose “no,” what are the alternatives, short of pretending these neglected individuals do not exist?

If you live in one of 39 cities across the country, you can offer a little financial assistance through a more structured channel, by buying a “street paper” that sources about half its content from homeless and formerly homeless individuals. Street paper vendors buy copies of the newspaper at a price of 50 percent or lower than the cover price and sell it to the public, keeping the proceeds.

• Support Groups that Help the Homeless

Maryland’s Montgomery County, which set up the anti-panhandling web page, makes it easy to help its efforts: Simply text “SHARE” on your cellphone to 80077, and you can quickly and painlessly donate $5 to The Community Foundation for Montgomery County. According to Marie Henderson, the foundation’s director, the donations are distributed to nonprofits throughout the county that provide safety-net services.

An internet search in any town or county will produce many organizations that serve the homeless and welcome donations or volunteers.

• Give Alternatives to Money

Of course, “donating to or volunteering with an organization won’t change the fact that you still walk by people who beg or sleep on the street,” notes Michael Farrell, executive director of DC’s Coalition for the Homeless.

That’s why professionals like Donald Whitehead, director of men’s services at the Coalition for the Homeless of Central Florida (one of four states with more than half of the nation’s chronically homeless), practices what he calls “weekly random acts of kindness.”

“I carry items like warm socks, gloves and gift cards for McDonald’s in my briefcase,” he says. “Once a week, I give a person one of the items, along with a gentle hello. I think the human contact is as valuable as the gifts sometimes.”

Michael Austin, who works with Appleseed Humanity in San Luis Obispo, California, (another of the states with the highest number of chronically homeless), likes that idea. “Homeless people put more wear on their socks in a week than most folks do in a year. Another big need is toiletries like soap; most shelters only have the small-sized bars you find in motels.”

Chronically unsheltered individuals (177,373 on an average night in 2014) typically have had previous bad experiences in shelters, have difficulty following the strict rules … and/or have mental health problems that make decision-making difficult.

For Kevin, one of the homeless men sleeping on the street whom I encountered on my walk to work, I identified a need very specific to him. I had begun engaging with several of the men, at first with a “Hi” and a smile, then with a slice of homemade banana bread. They were all eager to chat, and I found myself beginning to keep a special eye out for Kevin, who told me over a few conversations that he had been homeless for four months after losing his job as a delivery truck driver. He was estranged from his family, and although he panhandled at first, he soon stopped. “People looked at me like I had leprosy or something,” he said. “I still have some pride left.”

One day he told me he’d managed to get a job at a car wash, but was spending too much of what he earned on the Metro to begin saving anything for rent. I located a nonprofit that employed youth to refurbish used bicycles, and made that, along with a secure lock, my contribution. Yes, I paid about $100 out of my pocket, but it was for a very specific purpose, and I controlled where it went.

Jay Levy, a Massachusetts-based social worker and author of “Homeless Narratives & Pretreatment Pathways: From Words to Housing,” suggests distributing a flyer with information on local services. However, Stoops observes that in most cases, when you see the same people sleeping on the streets for a month or more, it’s not because they are unaware of available services.

(Photo: Cindi Hobgood)These chronically unsheltered individuals (177,373 on an average night in 2014) typically have had previous bad experiences in shelters, have difficulty following the strict rules by which these facilities are run and/or have mental health problems that make decision-making difficult. In fact, every single one of the homeless people on the streets whom I interviewed over the past year were there because they refused to go to a shelter unless it was so cold they literally had no choice.

(Photo: Cindi Hobgood)These chronically unsheltered individuals (177,373 on an average night in 2014) typically have had previous bad experiences in shelters, have difficulty following the strict rules by which these facilities are run and/or have mental health problems that make decision-making difficult. In fact, every single one of the homeless people on the streets whom I interviewed over the past year were there because they refused to go to a shelter unless it was so cold they literally had no choice.

When I first met Kevin, my desire to fix problem situations went into overdrive, and I began calling emergency shelters and bringing him lists of possibilities. However, he shut that down pretty quickly. The emergency shelters for single men, he told me, are like “jails.” Other adjectives I heard from my growing list of homeless acquaintances were “dangerous” and “dehumanizing.”

Lesson No. 1, for me, was that even the homeless remain their own agents and have the right to make their own decisions. Likewise, just because they are seemingly homeless, do not assume that all of their needs are the same. For example, Tina didn’t need socks or even food packets. It pays to learn a little about why they are on the streets.

If someone is persistently sleeping outside, Stoops recommends calling a city’s homeless hotline, or a local shelter, to make sure these individuals are least on their radar. If not, ask if they can send an outreach team.

“The real question should be, ‘Is this person known?’ ” agrees Maguire of 100,000 Homes, a national movement of communities working together to find permanent homes for the country’s most vulnerable individuals and families. “If not, it’s a death sentence.”

“Most people just don’t know how to approach us,” says Roxanne. “But it’s easy. Just stop a minute. Say good morning. Smile. We’re both human, right?”

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.