Honest, paywall-free news is rare. Please support our boldly independent journalism with a donation of any size.

Much of the South River Forest, or as activists call it, Weelaunee People’s Park, has been clear cut. In a token gesture to the community, the city talked about opening a handful of trails in slivers of remaining public land. But driving past the original site of the occupation, there isn’t a tree in sight to hang a hammock on. At nearly 5:30 pm on a Saturday, three bulldozers rumble across the land, rearranging splintery piles of red dirt. Shadowbox Studios, also licensed to use the site, has completed construction. Ringing the perimeter of both, cop cars lurk, waiting for signs of trouble. I started counting in my head, then had to switch over to tally marks. Even taking photos is de facto forbidden; I was followed and then pulled over while trying to take photos from the street. By my count, 26 police vehicles were surrounding the site. The only sign of the previous occupation was a downed yellow tower, charred at the base, with “Defend the Atlanta Forest” written in green paint. In a tragic echo of the activists’ thriving mutual aid camps, the cops set up a couple tents of their own, where they could eat snacks out of a few metal trays and retreat to shade no longer provided by the Atlanta forest.

Coming into the week of action that took place June 24-July 1 — a week of protests, targeted boycotts and joyful celebration in nature designed to call national attention to Cop City — the threat of police repression weighed heavily on activists’ minds.

At Saturday’s opening carnival, one Atlantan, who wished to remain anonymous, was hard at work spray painting more t-shirts. Wearing handmade pinecone earrings and blue paint flecked combat boots, he painstakingly laid out foam letters as stencils. His own shirt said, “I can’t protest Cop City.” But upon request, he’d also make “I can protest Cop City” shirts.

“It’s about [addressing] the fear,” he explained. “Having solidarity with the people who are too afraid to protest. There’s the uncertainty and financial risk. It’s hard to evaluate risk — police stormed a protest downtown advertised as a vigil. I’m really rolling the dice about whether people will be holding hands or burning cars, or whether people holding hands will be attacked by police.”

Early on, he explained, local nonprofits organized events in solidarity with the Defend the Atlanta Forest movement. The activist took pains to explain that this interview could in no way be affiliated with the small nonprofit he represents, and actually, it might be better if the entire interview were anonymous. Nowadays, he said, solidarity with Stop Cop City is “just a way for a small nonprofit to fall apart.”

I asked him what he meant. “You’ll get arrested and put in jail on trumped up charges. Look at what happened to the Atlanta Solidarity Fund.” I couldn’t argue with that.

He gestured towards the need for larger, national nonprofits, orgs with resources to be engaged in the struggle. “The Sierra Club can fight if people get arrested. Small orgs can’t.”

Everyone Who Participates Is at Risk

Yet, despite the fear, activists have descended on Atlanta in droves. Precautions are taken to ensure activists’ safety. Most of the activists on the ground engage in best practices concerning digital security. News of police activity spreads quickly. At the same time, activists are cautious to not spread fear. “Descriptive and objective” are the words of the day. The movement has good reason to be paranoid, but fear and rumors can also infect the movement and stifle organizing. From the outset, activists have adopted “forest names.” As police repression has escalated, the forest defenders change names more often. There’s a tension in the movement, because getting the word out often requires a public face. A handful of activists have become prominent on Twitter, and the movement is highly effective at putting out anonymous communiques on social media.

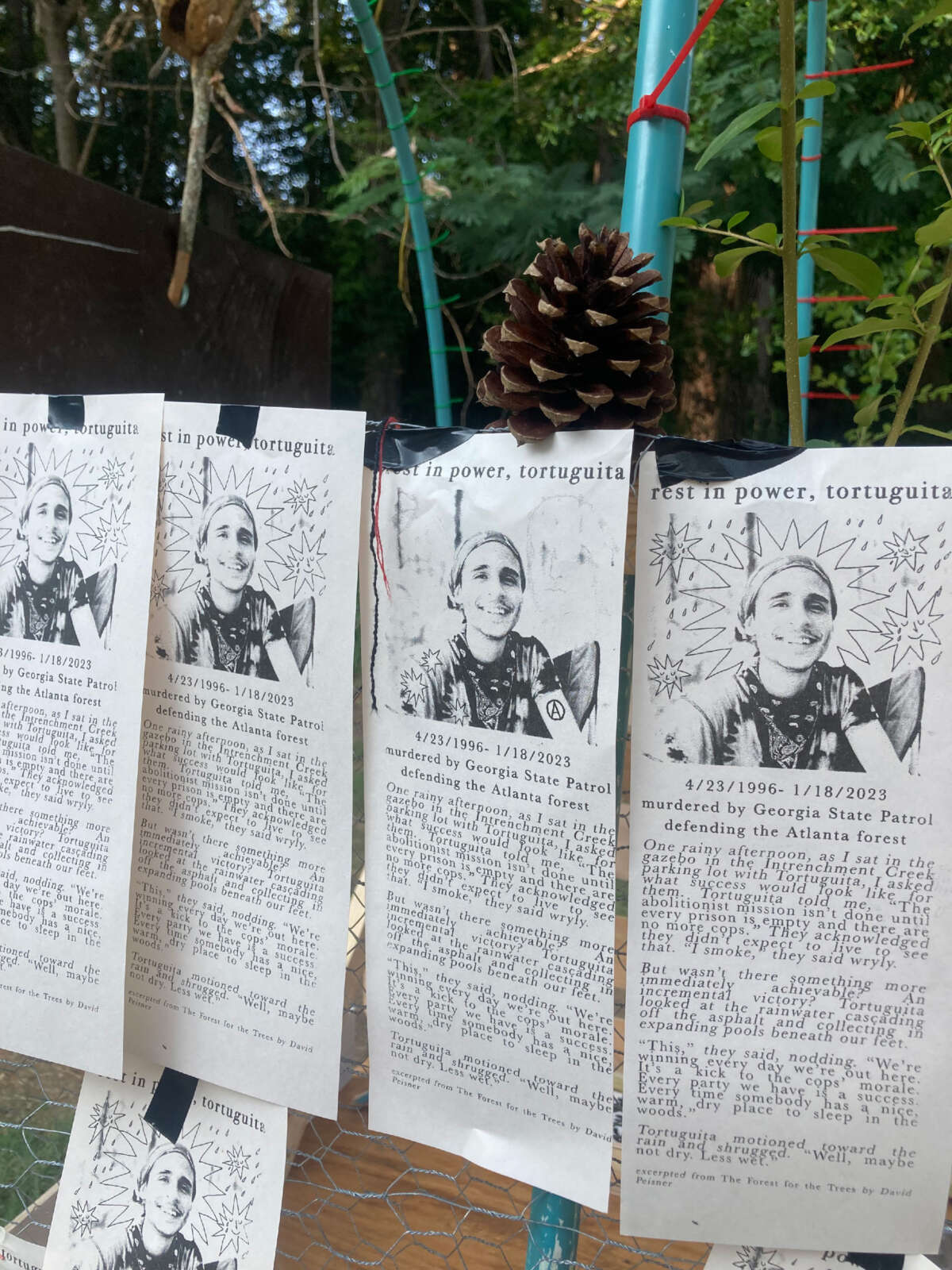

To many activists, the risk is still extremely high — and hard to predict. In late April, three activists were arrested on charges of felony intimidation of a law enforcement officer for distributing flyers calling Jonathan Salcedo a murderer for participating in the police killing of Tortuguita. The charge can carry up to twenty years in prison. The arrest warrants relies entirely on Salcedo’s own complaints: “Jonathan stated that he felt harassed and intimidated by individuals handing out these flyers.” Activists took pains to comply with the law; they placed flyers on the outside of mailboxes because they’d learned that mail tampering could be a crime. Seven weeks later, one of the activists arrested for flyering remains in jail.

Parts of the movement have pivoted to a more cautious approach after dozens of activists were put in jail or placed under bond conditions. In the assessment of an anonymous activist, “Prosecutors are grasping at straws. They’re stalling for time. They want to hurry and get this Cop City built, so they’re doing all sorts of things to distract us and make us busy so we’re doing other things instead of stopping Cop City. With every arrest, that’s one more person jail support has to care for. It’s more money the movement has to raise to post bail. We have to be very careful. If you’re going to burn a bulldozer, don’t get caught.”

The occupation has shifted to Brownwood Park, north of the Weelaunee Forest, in an attempt to evade police crackdowns. Still, the activists worry about police repression. One seasoned activist, identified by the pseudonym Jordan, used to camp in the Weelaunee Forest, but stopped after Tortuguita was murdered by police. “When Tort was murdered, it was really scary. Tortuguita was sleeping in a tent in Intrenchment Creek Park — not on Atlanta Police Foundation land — when the raid happened. They were allowed to be there, it was during the day. I care about the forest, but also don’t want to die. So I got into jail support, and then LEAF [an activist solidarity house] was raided.”

Parts of the movement have pivoted to a more cautious approach after dozens of activists were put in jail or placed under bond conditions.

Jordan led an arrest workshop during the week of action for forest defenders; they’ve been arrested at environmental protests across the country. But usually, they said, there’s a typical playbook.

“Other places have rules of engagement. Normally, there’s red roles. Those people knock down pieces of equipment or climb trees. Then there’s the orange roles. Orange roles are helping people in the tree. Green roles aren’t breaking the law and aren’t planning on breaking the law.”

But in Atlanta, Jordan explained, police and prosecutors have sought to undercut the movement by targeting the support systems. “Here, green roles don’t exist. They’re trying to arrest people on the periphery. They arrested kids who came to the music festival, people without strong ties to the community. Not everyone who goes to a music festival has thought about being arrested.”

The recent arrests of Atlanta Solidarity Fund organizers, who coordinated bail funds and jail support for imprisoned activists, are an egregious example of this type of repression. Usually in movements, jail support carries a low risk of arrest. But in Atlanta, Jordan said, “there is no green role in this life. The Atlanta Solidarity Fund was supposed to be the greenest of green roles and their house got raided!”

Fear of Repression Drives Out Activists

On Saturday, June 24, as the sun was setting, activists put finishing touches on an altar to Tortuguita. The altar was a cart on wheels, designed to be mobile in case of a police raid. (Previously, police destroyed an altar to Tortuguita set up in Weelaunee Forest, to the outrage and grief of activists.) Friends of Tortuguita notched photos in the chicken wire lining the cart and painted a sign with a quote attributed to Tort: “Deep grief can exist at the same time with totally transcendent bliss.” According to the public schedule, the vigil was supposed to happen at 8:30 pm, but the activists were running late. Someone came running up the trail. “Cops at the north side!” The activists lounging in hammocks, washing dinner dishes and tending to the altar converged on the police. As a “friendly warning,” Atlanta police sent at least 20 officers to march through the park, right at the scheduled time of the vigil. Most if not all were armed; all wore bulletproof vests. Officers yelled, “Park closes at 11!” One of the activists asked for a time check. It was 8:41 pm — over two hours before the park was slated to close.

Outnumbering the cops almost two to one, the activists followed the cops through the park, first clapping in unison in the otherwise silent park, then chanting “Viva, viva Tortuguita!” and “If you build it, we will burn it!” Confronted by the activists, the cops fanned out in groups of three and four. At a signal, they left the park with activists still trailing them. Outside the park, a procession of cop cars stood guard. The forest defenders were in the park lawfully; the police presence was a show of force intended to intimidate.

After the cops left the park, the vigil began. Tortuguita’s mom, Belkis Terán, called for strength and joy amid sorrow, saying: “Some of you are scared. Some of you may go to jail. But still here we are.” A slight figure hunched over a prayer candle, she led the gathered activists in a meditation: “I’m sorry. Forgive me. Thank you. I love you.” Helicopter noise broke through the murmured echoes of the meditation, and police cars circled the park with lights flashing. Several other police cars parked across the street. As soon as the vigil concluded, the edges of panic began to break out over the crowd. “We’re going to have a conversation about what happens next. Now,” said one activist. Over the next several minutes, the crowd discussed whether to stay or go. The consensus was clear: Staying to be arrested would cut the week of action short early. Within 45 minutes, the activists had packed up their tents, loaded Tortuguita’s altar onto a truck, and collapsed the kitchen and handwashing infrastructure supporting the camp. Forest defenders filed out in small groups, and by 10:40 pm, only press, legal observers and a handful of activists chasing out stragglers remained.

“I could have stayed and gotten arrested,” one activist reflected. “But that would not have been a good protest. There’s proper times to risk arrest.”

Still, the cops seemed keen to catch anyone failing to comply with Brownwood Park’s posted hours. Police shut down the roads cutting through Brownwood Park and officers amassed at the park’s edges. Several clearly identified members of the media stood on the sidewalk filming police. The cops shined high beams into their eyes, blinding cameras. I circled the park in my car, filming the police. When police officers noticed I was filming, a cop car pulled out to follow me. A police officer read out my license plate number into the dispatch radio loud enough that I could hear them from my car. I took their actions as an implicit threat that I would be followed and harassed should I continue filming. The police finished their sweep of the park without making a single arrest. Fourteen cop cars filed out, an excessive show of force intended to intimidate and dissuade protesters from occupying the park. Activists were forced elsewhere — to friends’ houses, to deeper, darker patches of woods, to places they could occupy outside of cops’ easy grasp.

Activists are Treated as a Domestic Insurgency

On Wednesday night, Stop Cop City activists had planned a “March for the Forest” intended to reclaim the parts of the forest not yet destroyed by clearcutting. A sense of anxiety and excitement was in the air as activists discussed once again occupying Weelaunee Forest. But, as activists amassed, one helicopter, then two, began circling overhead. People running the free food distribution adjacent to the park reported overwhelming numbers of police. In the end, organizers decided to halt the march only a third of the way along its intended route, to shield activists from the brute force of state repression of the movement.

Tortuguita’s mom, Belkis Terán, called for strength and joy amid sorrow, saying: “Some of you are scared. Some of you may go to jail. But still here we are.”

“We deliberated about what we could do, what we wanted to accomplish,” said one of the speakers at the rally. “The people we’re fighting against believe that we are a domestic insurgency.” He pointed out that a protester had been arrested that morning at a demonstration against Cadence Bank, the institution giving a loan to the Atlanta Police Foundation to build Cop City. The activist was arrested on a public sidewalk in broad daylight, allegedly for throwing meat at a police officer. They were slapped with charges of assault and obstruction. Small protests in public space, actions that would elsewhere carry a low risk of arrest, here have been met with a heavy police presence and arbitrary arrests. The First Amendment is in sorry shape in Atlanta, where police flock to protests in huge numbers to intimidate activists, and prosecutors have continually pursued charges wildly out of proportion to the alleged crimes committed.

“Our enemy is treating us like terrorists, right?” continued the activist. “It’s not just a rhetorical trick. So, we have to figure out how we’re going to win.… We’ll go on the offense how we’re able, when we’re able.” But retaking the forest right then, with police cars lying in wait, would incur a heavy cost. The activists retreated. Reclaiming the forest would have to happen another day.

Police Intimidation Fails to Break Solidarity

Despite the fear, despite the repression, the movement to Stop Cop City is flourishing. The week of action features a deep calendar of crowd-sourced events, ranging from knitting circle skill shares to talks by longtime local activists on the historical roots of the Stop Cop City movement. There are signs of hope — last week, DeKalb County District Attorney Sherry Boston announced that she will not prosecute domestic terrorism cases against protesters. The Intercept reported that internal notes suggested earlier misgivings about prosecuting Thomas Jurgens, a legal observer arrested and charged with domestic terrorism. The Georgia Board of Public Safety meeting register noted, “Dekalb County wanted to drop the charges on the attorney from the Southern Poverty Law Center who was arrested from this incident, and the Attorney General said no.” State Attorney General Chris Carr remains committed to prosecuting alleged protest-related offenses as domestic terrorism, but other officials are increasingly getting cold feet. Just last week, the head of the Georgia Bureau of Investigation resigned less than a year into the job.

The movement has exhibited remarkable resilience. As protesters at the fringes get arrested, Jordan says “we’re building those connections” through jail support and solidarity. One activist stuck in jail for 29 days received over 500 letters. “They had a Santa bag when they left jail,” Jordan said. The week of action calendar lists solidarity events in Milwaukee, Philadelphia and Galveston, with protests set to trigger in Phoenix, Tucson, Savannah, Boise, New York City, Chapel Hill, Charlotte, Portland, Richmond and Washington, D.C. if forest defenders are arrested.

There’s a sense in the movement that they’re winning. Local activist Micah Herskind pointed out on Twitter that even Republicans fundraising off Cop City are using the activists’ terms. On June 26, the Atlanta Solidarity Fund announced that it can begin accepting donations again. Then there’s the best proof — the hundred or so activists braving the police and prosecutorial war against the movement by showing up in Atlanta to cook together, and play “rowdy riot tag,” and show up in droves to public comment periods and protests.

Despite the shadow of repression, the movement is thriving.

Press freedom is under attack

As Trump cracks down on political speech, independent media is increasingly necessary.

Truthout produces reporting you won’t see in the mainstream: journalism from the frontlines of global conflict, interviews with grassroots movement leaders, high-quality legal analysis and more.

Our work is possible thanks to reader support. Help Truthout catalyze change and social justice — make a tax-deductible monthly or one-time donation today.