Support justice-driven, accurate and transparent news — make a quick donation to Truthout today!

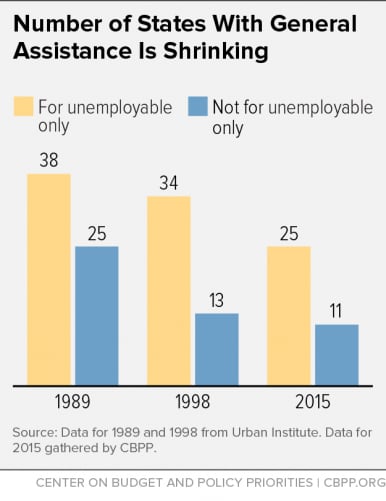

State General Assistance (GA) programs, which provide a safety net of last resort for those who are very poor and do not qualify for other public assistance, have weakened considerably in recent decades and are continuing to do so, despite ongoing need for aid in the wake of the recession. The number of states with General Assistance programs has fallen from 38 to 26 since 1989, and benefits have shrunk in inflation-adjusted terms in nearly every state since 1998.

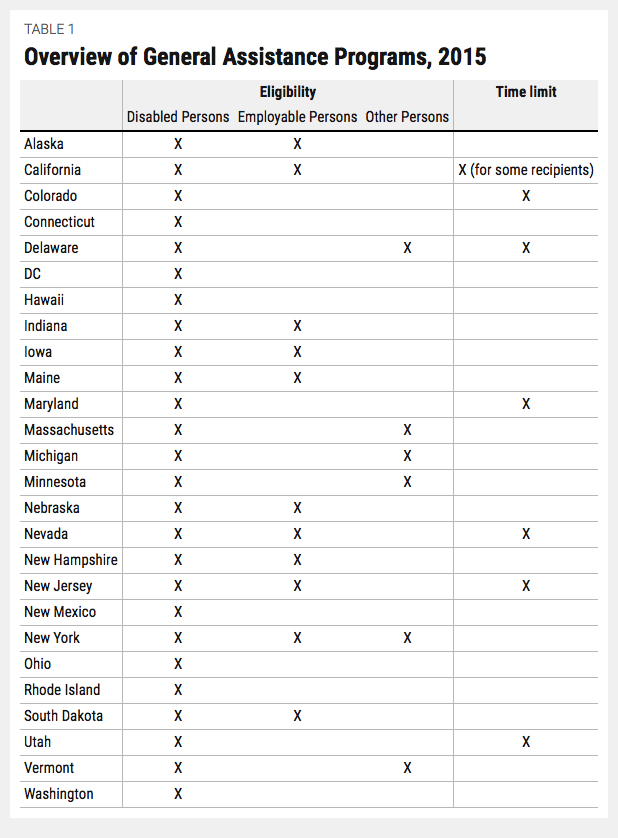

The 26 states with GA programs generally serve very poor individuals who do not have minor children, are not disabled enough to qualify for (or do not yet receive) Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and are not elderly.[1] Only 11 of the 26 states provide any benefits to childless adults who do not have some disability; the others require recipients to be unemployable, generally due to a physical or mental condition. (See Figure 1.)

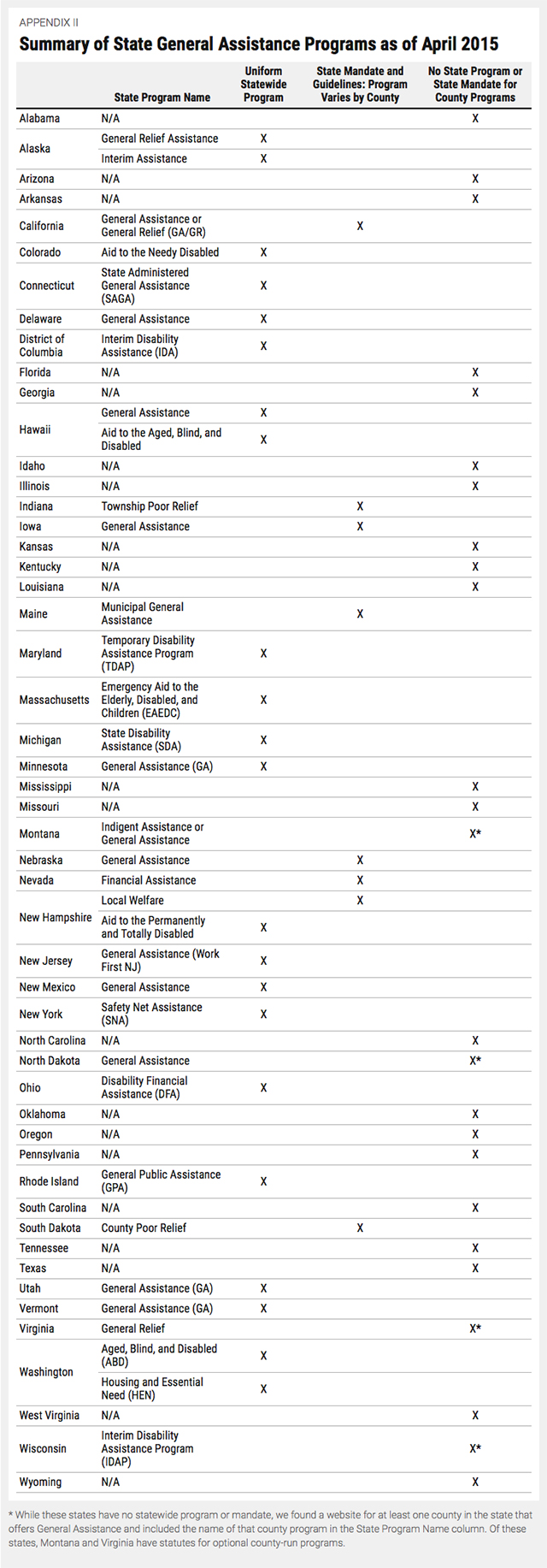

There is no federally supported cash safety net program for poor childless adults who do not receive SSI; Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) only serves families with minor children. Thus, state or local GA programs are generally the only cash assistance for which such individuals can qualify. Some are uniform statewide programs; others have mandatory state guidelines but allow county programs to adopt varying eligibility standards. (See Appendices II and III for greater detail.)

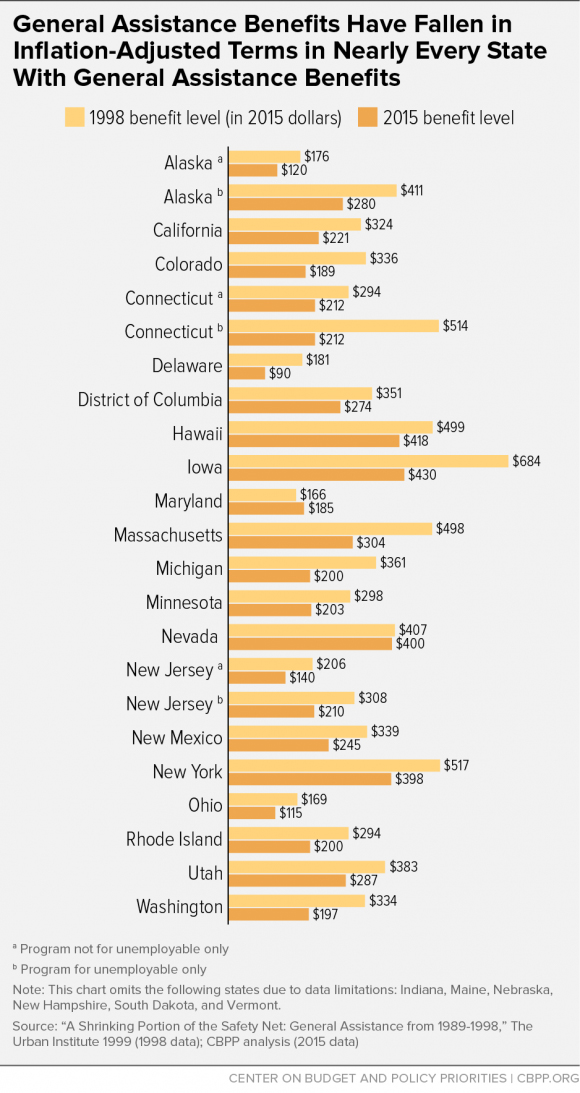

General Assistance benefits are extremely modest. In nearly all states, the maximum benefit is below half of the poverty line for an individual; in half of those states it is belowone-quarter of the poverty line. In many states, benefit levels have not changed in decades and thus have declined in real (inflation-adjusted) dollars. Some states have cut benefits further, reducing them in nominal dollars. Some other states have raised benefits at some point over the last 25 years, but generally not by enough to restore the lost purchasing power.

In recent decades, a number of states have eliminated their General Assistance programs, while many others have cut funding, restricted eligibility, imposed time limits, and/or cut benefits. Between the late 1980s and late 1990s, 12 states eliminated General Assistance for people who are not disabled and three other states eliminated their state GA programs altogether. Between 1998 and 2010, five additional states terminated their GA programs, and at least ten other states cut their programs back. Since 2011, three more states have ended their statewide programs and several others have reduced funding or tightened eligibility.

This report describes the weakening of General Assistance programs over the years and provides an overview of program policies across the 26 states with programs in 2015. The information in this report is based on our updated national survey of General Assistance programs.[2]

Overview of General Assistance Programs

As of April 2015, 26 states had a GA program that either operated statewide or was mandated and governed by statewide guidelines. (See Figure 1.) This section reviews key eligibility provisions and related benefits for these states; see Appendices II and III for more details.

Eligibility Groups

Every state General Assistance program offers benefits to individuals with disabilities. Some programs also assist other individuals.

-

Individuals with a disability. General Assistance programs in 26 states serve needy individuals who are unable to work due to incapacity or disability but are not receiving SSI. In some of these states, disabled individuals may be served through a program that assists employable and disabled individuals alike, solely because of their financial need. Most of these 26 states, however, have a program that only serves individuals who are disabled or otherwise considered unemployable.

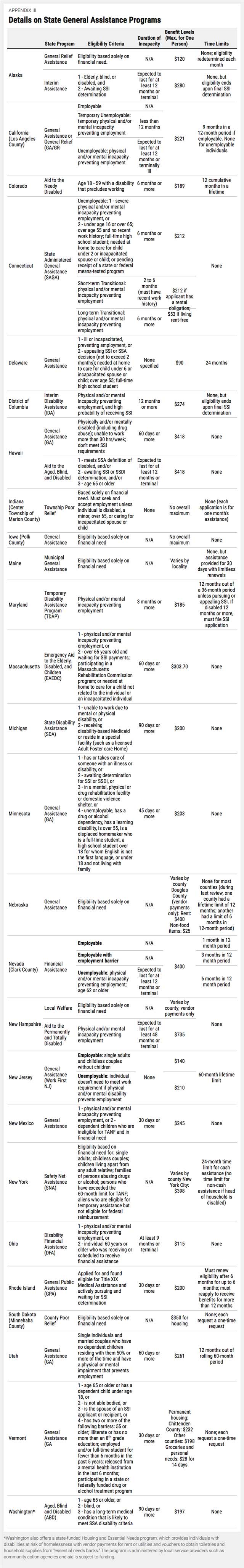

States requiring the individual to be disabled require some type of medical documentation of incapacity. State policies vary in the severity of the disability that qualifies an individual for General Assistance, ranging from a temporary inability to work due to incapacity to the much more severe SSI disability standard. Some of the states using the SSI disability standard require General Assistance recipients to apply for SSI, often requiring them to sign an interim assistance agreement to repay the state once they begin receiving SSI. Thirteen states require a minimum duration of disability – that is, the disability must be expected to last for anywhere from at least 30 days to at least 48 months, depending on the state.

-

Other unemployable individuals. In addition to individuals with a disability, seven states serve other categories of individuals who are considered unemployable because they are, for example, over age 55, have a learning disability or limited literacy that prevents employment, or are needed at home to care for a young child or a disabled family member.

-

Employable individuals. Some 11 states assist individuals who are employable but ineligible for other public assistance programs. These states also serve unemployable individuals, either in the same program or a separate program; some states have different eligibility criteria, benefit levels, or administrative structure for employable and unemployable individuals. For example, in New Jersey, maximum benefits are $140 per month for an employable recipient and $210 per month for an unemployable recipient.

Time Limits

Seven of the 26 states limit how long an individual can receive aid, but time-limit policies vary.[3]

-

Three states impose a lifetime limit for anyone receiving benefits. Colorado, Delaware, and New Jersey have cumulative lifetime limits of one, two, and five years, respectively.

-

Three states have intermittent time limits for anyone receiving benefits. In Maryland, individuals may receive benefits for 12 out of every 36 months; in Utah, 12 out of every 60 months. In Nevada, individuals may receive benefits for one, three, or six months per year, depending on their employability.

-

One state has time limits for a subset of recipients. In California, employable recipients can receive benefits for nine months out of every year.[4]

Benefit Levels

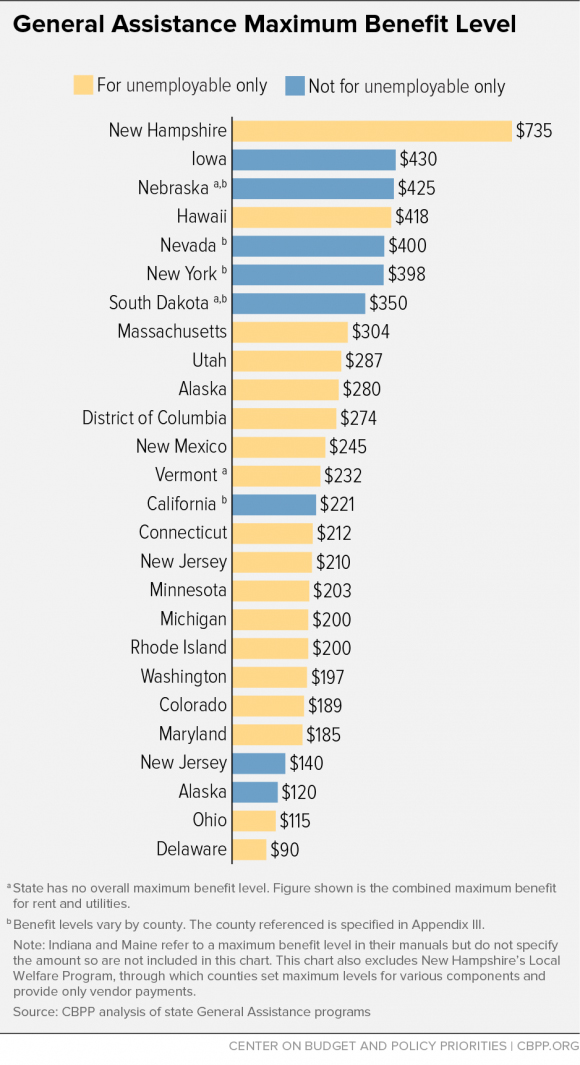

General Assistance benefit levels are very low. Most state or county guidelines set maximum standard benefit levels. These maximum levels are below half of the federal poverty level for an individual in all programs but one (New Hampshire’s Aid to the Permanently and Totally Disabled) and below one-quarter of the federal poverty level in most programs.

Some states provide benefits to recipients either in cash or through vouchers; others make all payments directly to landlords or service providers. Although the specific needs covered vary by state, GA benefits are intended to help recipients meet basic needs such as shelter and utilities.

Some of the states with the lowest benefits only serve individuals whom the state has found to be unable to work and are therefore, by definition, unable to supplement their benefits with earnings. (See Figure 2.) The median monthly benefit is $211 for programs serving only unemployable persons, compared with $374 for programs that also serve employable persons. For example, Delaware and Ohio, which serve only unemployable individuals, set the maximum benefit level at $90 and $115, respectively.

General Assistance Has Eroded Severely

General Assistance has become a much weaker safety net over the years. Many states have eliminated their programs or scaled them back by reducing funding, imposing tighter eligibility restrictions and/or time limits, and/or reducing benefits. These cutbacks continued during and after the recession despite high unemployment and a rise in the number of jobless workers who have exhausted their unemployment insurance benefits. Consequently, a growing number of needy individuals have no cash assistance or similar income support.

Between 1989 and 1998, Montana, South Carolina, and Wyoming eliminated their state General Assistance programs altogether and 12 other states eliminated GA for employable individuals, while continuing some aid to unemployable persons. By 1998, only 13 states offered any aid to individuals considered employable. (See Figure 3.) Between 1998 and 2010, another five states – Arizona, Idaho, Missouri, Oregon, and Wisconsin – eliminated their statewide programs,[5] and Utah eliminated General Assistance for employable childless individuals (while maintaining it for unemployable people).

Most recently, Illinois, Kansas, and Pennsylvania eliminated their state GA programs in 2011 and 2012. Illinois initially withdrew state funding from all municipalities except Chicago and then withdrew funding for Chicago in 2012, ending the city’s GA program. Any remaining General Assistance programs in Illinois are solely funded and administered at the municipal or county level.

Most recently, Illinois, Kansas, and Pennsylvania eliminated their state GA programs in 2011 and 2012. Illinois initially withdrew state funding from all municipalities except Chicago and then withdrew funding for Chicago in 2012, ending the city’s GA program. Any remaining General Assistance programs in Illinois are solely funded and administered at the municipal or county level.

Almost all the states that did not eliminate their programs over the last two decades provide lower benefits now than in 1998, after adjusting for inflation, as Figure 4 shows. Among the 20 states for which we have comparable data, only Maryland’s benefits exceed the 1998 level, and Maryland’s benefits are extremely small – less than one-quarter of the federal poverty line.

Since 2011, five states have raised benefits in nominal terms (Colorado, District of Columbia, New Hampshire, New York, and Utah) while four states have cut them (Delaware, Michigan, South Dakota, and Washington).

Health Coverage for General Assistance Recipients

Under the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA), states can extend Medicaid eligibility to all individuals at or below 138 percent of the federal poverty line. Previously, states could not receive federal matching funds to provide health coverage to non-disabled, non-elderly childless adults without a federal waiver. The ACA provision allows low-income childless adults, including those receiving General Assistance, to qualify for Medicaid. However, the Supreme Court in 2012 made this Medicaid expansion a state option, which 29 states have taken up to date.

Most of the 26 states with statewide General Assistance programs have expanded Medicaid. GA recipients in these states generally should qualify for Medicaid, although they may have to go through a separate application process.

In some states, General Assistance recipients with severe disabilities may qualify for Medicaid through a disability-related category rather than through the state’s Medicaid expansion. Some states may also provide some state-funded health coverage to a subgroup of General Assistance recipients who may not qualify for Medicaid.

In the five states with statewide General Assistance programs that have not yet taken up the Medicaid expansion – Alaska, Maine, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Utah – policies in each of these states may provide coverage to some GA recipients:

-

Recipients of Alaska’s interim assistance may qualify for Chronic and Acute Medical Assistance or Medicaid.

-

Maine provides financial assistance for pre-approved medically necessary services.

-

Douglas County, Nebraska enrolls all GA recipients found to be medically indigent in the Primary Health Care Network.

-

Minnehaha County, South Dakota covers emergency services for GA recipients, as well as non-emergency services when funds are available.

-

In Utah, GA recipients can apply for health coverage through the Primary Care Network if enrollment is open to childless adults.

Conclusion

By and large, the federal government has left it up to states to provide basic assistance to childless adults who do not meet the severe disability standard to receive SSI. States have never provided substantial support for this group, and the safety net for these individuals has weakened significantly over the past 25 years and continues to erode. Few states serve employable childless adults, despite the large number of workers who have exhausted their unemployment insurance benefits and are vulnerable to severe hardship.

Moreover, half of the states have no statewide General Assistance program for individuals even if they are unable to earn income to meet their basic needs due to disability. And many of the states that do serve individuals with disabilities have tightened eligibility or imposed time limits despite ongoing disability. In addition, the value of General Assistance benefits has eroded in real dollars in nearly every state. In sum, there is no effective safety net for childless adults that is broadly available across the nation.

Appendix I: Methodology

We collected information on General Assistance current policies and proposals for 2015 by checking state and county public assistance agency websites (including manuals and rules) and directly contacting agencies or advocates in states to seek or confirm information. We looked at policies and benefit levels as of April 2015 and indicated where we have information on any subsequent changes.

Not all state programs are named “General Assistance”; we included state-funded programs available to individuals who are ineligible for other forms of cash public assistance. As a result, we included programs with names such as Interim Assistance, State Disability Assistance, and Local Welfare (see Appendices II and III). Some state General Assistance programs also serve families that are ineligible for other aid; we have included this information in Appendix II, but the details in this report focus on program features that apply to individuals.

For historical information, we relied on reports from the Urban Institute, which include information for 1998 and comparative information back to 1989. The Urban Institute has published several comprehensive national surveys of General Assistance programs; its most recent published data is from a 1998 survey of states and a shorter policy brief.[6] Because we compared 2015 program information to the 1998 and 1989 data from the Urban Institute to make comparisons across time, we generally followed the Urban Institute classifications for states with county variability and gathered information for the same county used for the earlier Urban reports (which was, and often still is, the county with the largest population). In some cases, we included different information or classified it differently than in the earlier Urban Institute reports.[7]

This report focuses on the 26 states with either a statewide program or statewide mandate for county or local programs. Some counties in some other states may operate their own programs; Appendix II provides the information we collected but is not necessarily comprehensive. (We did not otherwise collect information on specific county programs.) In some cases where historical data from the Urban Institute indicate that a county in such a state operated a program in the past, we were unable to find evidence that the county still offers the program but cannot say with certainty that it no longer does.

End Notes:

1. These 26 states include the District of Columbia, which this report treats as a state. The remaining 25 states have no statewide GA program or state mandate for counties to provide such assistance, although some counties may offer a program at the county or local level in some of these states. Because there is neither a statewide program nor state mandate, we consider these states as having no program in Figure 1. In four of the states labeled as “No State Program” we have identified at least one county with a GA program; those states are identified in Appendix II.

2. This paper is an update of our 2011 report, “General Assistance Programs: Safety Net Weakening Despite Increased Need.” Appendix I sets forth the programs for which we collected data and how we collected it. It also discusses other studies on which we relied for historical information.

3. New York is not included as having a time limit here. It has a two-year limit for cash assistance, which does not apply if the head of the household is disabled, but no time limit for assistance provided through vouchers for rent and utilities, which is how it provides most aid. Thus, regardless of the time limit, aid is provided in some form to individuals.

4. The California information is based on the Los Angeles County program. Some other counties have different time limits; many have a limit of three months out of every 12. Other California counties also have different – and generally higher – benefit levels than Los Angeles.

5. Idaho eliminated its Aged, Blind, and Disabled program in 2010. Although the state statute still refers to General Assistance and at least one county (Ada County) continues to offer one, aid there is provided to recipients for only one month in a year, which the Urban Institute and this report consider emergency assistance rather than General Assistance.

6. L. Jerome Gallagher et al., State General Assistance Programs 1998, The Urban Institute, 1999; L. Jerome Gallagher, “A Shrinking Portion of the Safety Net: General Assistance from 1989 to 1998,” The Urban Institute, 1999.

7. For example, we included New Hampshire’s Aid to the Permanently and Totally Disabled program in this report because we concluded that it was comparable to other state General Assistance programs, although the Urban Institute included only New Hampshire’s Local Welfare in its reports.

Thank you for reading Truthout. Before you go…

…We ask that you take just a second to read this message.

We are up against a far-reaching, wide-scale attack on press freedom coming from the Trump administration. Since his inauguration last year, we’ve seen frightening censorship, a right-wing takeover of the news industry, and worsening financial conditions for progressive nonprofits across the board.

We can only resist Trump’s agenda by cultivating a strong base of support. The right-wing mediasphere is funded comfortably by billionaire owners and venture capitalist philanthropists. At Truthout, we have you.

We need your help to sustain the fight against authoritarianism in 2026. Please take a meaningful action in this fight: make a one-time or monthly donation to Truthout. If you have the means, please dig deep.