New data reveals, as we will show below, that Europe is the sick man of the global economy once again. But more to the point, it is high time to acknowledge that the European Monetary Union (EMU) is, for all practical intents and purposes, no longer viable.

Ever since the latest global financial crisis begun in 2008, Europe’s monetary union is mired in a severe economic crisis from which it is simply unable to recover. For starters, the euro crisis has had a devastating impact on the peripheral eurozone countries (Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain, Italy and Cyprus), and it consolidated even further the division between north and south, thus putting permanently to rest illusive notions like convergence and cohesion inside the EMU.

The crisis management approach adopted on their behalf by the core euro-zone countries – Germany in particular – made things much worse. The so-called “rescue plans” enforced by the troika of the European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for the crisis-ridden euro member states (Italy excluded) ravaged the southern economies as the harsh austerity policies administered caused massive declines in domestic demand and sharp rises in long-term unemployment, brought about brutal cuts in social programs and public investments, and resulted in rapidly declining standards of living and large-scale migration.

Five years after the financial crisis of 2008 reached Europe’s shores, the euro crisis is not only not slowing down, but it is actually spreading, affecting more and more member states and giving rise in turn to growing popular discontent about the European integration process with far-reaching and unforeseen consequences.

GDP in Spain, Portugal, Ireland, and Italy is on the average 7 percent below the pre-crisis levels; Greece’s GDP is nearly 25 percent below its pre-crisis peak. The latest Eurostat data show that the unemployment rates in the peripheral countries are stratospherically high, indicating that there is no recovery. In Greece the official unemployment rate is over 26 percent while in Spain it is nearly 25 percent. In Portugal it is 14 percent, in Italy 12.3 percent, and in Ireland (the country with the highest net migration level in Europe) at over 11 percent.

In addition, all of the bailed-out countries have seen their public debt ratios explode, leaving them in a state of debt bondage and permanent austerity from which they are unlikely to escape any time in the foreseeable future. In Greece, government gross debt exploded from 126.8 percent at the end of 2009 to 175 percent at the end of 2013 (and is expected to grow to exceed that mark by the end of 2014); Spain’s public debt ratio grew from 52.7 percent in 2009 to over 92 percent at the end of 2013 (and is expected to reach the historic mark of 100 percent by the end of 2014); Ireland’s grew from 62.2 percent in 2009 to over 123 percent at the end of 2013; and Portugal’s, from 83.6 percent in 2009 to 128 percent at the end of 2013. (1)

Five years after the financial crisis of 2008 reached Europe’s shores, the euro crisis is not only not slowing down, but it is actually spreading, affecting more and more member states and giving rise in turn to growing popular discontent about the European integration process with far-reaching and unforeseen consequences. (2)

All across the Eurolands, socially intolerable levels of unemployment, stagnating and/or declining wages and lack of growth prospects work in tandem with the undemocratic status of eurozone governance – the illegitimate policies dictated mainly by Germany – and the lack of a vision for the future either at the domestic or the European level to produce a European public sentiment that is increasingly Euroskeptic and in fact outright hostile to further integration. (3)

It has been widely noted that European policy has been quite short-sighted in dealing with the euro crisis because the policies pursued aimed at buying time and nothing more. This is true, but in a partial and rather superficial manner only as this line of criticism ignores the fact that the European integration project is built on extreme neoliberal premises and assumptions about economic growth and development that leave little room for the kind of policy thinking, let alone policymaking and implementation, that the so-called “master-economist” envisioned and articulated in an attempt to address the crisis of capitalism of the 1920s and the Great Depression of the 1930s. (4)

Moreover, the evolution of European economic integration since the Maastricht Treaty has rested on rather undemocratic political foundations, thereby de facto excluding claims based on empowered participation, for the explicit aim has been principally to serve the goals and interests of European capital and European corporations rather than the common good of Europe’s citizens.(5)

The European integration process has always been about strong states imposing their will on weaker ones and international capital finding wider and more open space in which to operate and thus to run roughshod over domestic labor. The bailout schemes serve as unquestionable testimony to the eurozone’s antidemocratic governance and imperial bent.

The German model is actually responsible for the internal imbalances that initially imploded in the area under the euro regime.

In this context, the structural adjustment programs conceived with the assistance of the IMF for the over-indebted economies in the eurozone were a natural outcome of the purpose and design of the EMU. Neoliberalism is ingrained in the structures and relations of decision making in the EMU, including of course those in the ECB. The policies of wage reduction and austerity imposed on the bailed-out countries were guaranteed to bring about a severe depression, yet the purpose was not to “rescue” their economies but rather the foundation of the eurozone and its respective banks. (6)

The collapse of economic activity was certain to cause a ballooning of public debt, but that was inconsequential as the burden would be passed on to the taxpayers of the bailed-out countries and the draconian austerity measures ensured its repayment at least for the foreseeable future. In the meantime, the debt menace was used as a sledgehammer to compel peripheral governments to proceed with further liberalization of the economy, the dismantling of the welfare state and the sale of public assets for bargain-basement prices.

The much talked about competitiveness issue is also couched by the euro zone leaders in neoliberal and imperial terms. The idea that all eurozone member states can run surpluses, as Germany does, with the improvement of their competitive position by lowering per-unit-labor costs in greater percentage than those of their neighbors is not simply a preposterous claim, but a recipe for social disaster. It involves a race to the bottom from which labor emerges totally impoverished while the rate of profit for big business and global corporations increases geometrically.

Germany has destroyed Greece twice in the last 70 or so years: once with the Nazi military invasion during World War II and now with its inhumane austerity agenda.

Indeed, it is hard to overlook the fact that the German model is actually responsible for the internal imbalances that initially imploded in the area under the euro regime as Germany has been pursuing policies since the early 2000s with the aim of producing an external surplus, which reached 7.5 percent of GDP in 2013 and is expected to be just as astonishingly high at the end of this year. (7)

As yet another example of the imperial logic and dynamic guiding governance in the euro zone, pact violations by Germany and France never produced any sanctions, but subsequent violations by Greece and Portugal unleashed Germany’s fury and demands that they be severely punished – which they were – with earth-scorching policies highly reminiscent of those applied by the brutal military regime of Augusto Pinochet in Chile under the auspices of the Chicago School boys and the IMF.

In Greece, the peripheral eurozone member state that has suffered as a result of the brutal austerity policies dictated by Germany an economic blow equivalent to those normally experienced by countries under wartime conditions, it could take at least 20 years for the nation’s GDP to return to pre-crisis levels. Indeed, Germany has destroyed Greece twice in the last 70 or so years: once with the Nazi military invasion during World War II (and where war reparations for the killing of hundreds of thousands of people and for a massive loan that was forcibly extracted from the Bank of Greece in 1943 were never made) and now with its inhumane austerity agenda. In fact, the prospects of growth are actually nonexistent under the current euro regime and with Germany as its hegemon.

In this context, what many current analyses of the Greek economy seem to overlook is that while a major restructuring of public debt (95 percent of Greece’s government debt is in the hands of the formal sector) is an absolute necessity for the domestic economy to receive some breathing space, the paths to growth and development still remain a conundrum (and for most of the euro area) as the crisis that broke out in the eurozone has actually led to more stringent fiscal rules, and four and a half years of brutal austerity have not produced the slightest change in the attitude of eurozone leaders toward Greece and its ailing economy.

The fiscal compact, which entered into force at the start of 2013, demands that the government budgets of the member states be in balance or surplus and that only those with a significantly lower than 60 percent government debt-to-GDP ratio may set the deficit limit to 1 percent of GDP. These policies are said to provide greater financial stability (this is while the euro zone is already the playground for bond hedge funds) but, by restricting the fiscal space even further, they actually enhance recessionary dynamics, thus ensuring economic and political instability by guaranteeing that Euroland will increasingly turn into an economic wasteland.

As indication of the severity of the lack of growth in the euro zone, Spain’s GDP grew by a mere 0.6 percent in the second quarter of 2014, making a highly indebted country with an unemployment rate of nearly 25 percent “one of the strongest performers in the euro zone.” (8)

The latest available data reveals a dismal outlook for the eurozone as a whole. Thanks to new GDP calculating methods introduced recently by Eurostat, GDP in the euro area increased by 0.1 percent in the second quarter of 2014 (when according to previous calculations there was zero growth quarter-on-quarter). (9) This is still a nearly zero growth rate and the main reason is because of contractions in the three major economies of the euro area: Germany’s GDP declined by 0.20 percent in the second quarter of 2014 over the previous quarter; Italy’s GDP also contracted by 0.20 percent in Q2, 2014; and France’s GDP for Q2, 2014 remained stagnant over the previous quarter. (10)

Much of the eurozone’s awful economic performance is attributable to the ills of industrial production, the output levels of which are below what they were four years ago (see Figure 1 below)

The usually reliable German economy, with its huge export machine, seems to be leading the way to a widespread eurozone recession: First, Germany’s exports took a huge nosedive in August, dropping by 5.8 percent (11) while its industrial production index declined by 4.3 percent from July to August – almost three times higher than the expected decline. (12)

Indicative of the mood that is beginning to prevail among investors over Germany’s economic model, which thrives on suppressing wages to sap domestic demand while subsidizing exports, a study by the Centre for European Economic Research (ZEW) in Manheim found that investors’ confidence in Germany has dropped for 10 consecutive months, (13) while the Munich-based economic institute IFO, which keeps track of business confidence in Germany, reported recently that its business climate index dropped for the fifth consecutive month.” (14)

It is simply remarkable that the euro zone’s GDP has failed to return even to its 2007 levels.

The German economy’s recent performance is seemingly so awful that it prompted ING economist Carsten Brzeski to describe it as “a summer horror story” and to add that “it needs a small miracle . . . to avoid a recession.” (15)

In the eurozone’s second largest economy, there is zero economic growth while unemployment is rising (already over 10 percent), and business confidence levels are lower than those in Germany and Spain. (16) Worse, France’s deficit (currently at 4.4 percent of GDP), is way above the expected 3 percent imposed by European Union budget rules, which means it will be extremely hard, if not impossible, for the “socialist” government of François Hollande to rely on expansionary fiscal policy to boost economic growth.

France’s budget for 2015, which was submitted to the European Commission in mid-October of this year, falls short of meeting the goals to reduce its structural deficit by 0.8 percent in 2015. The French government has indicated that it will not meet EU budget rules until 2017, setting up a possible confrontation with Germany and the EU chiefs. Still, it is unlikely that Germany and the European Commission will seek to humiliate France over its budget deficit (France is anyway a consistent violator of EU budget rules) because of the political repercussions that such an outcome might have inside France society, where Marine Le Pen’s National far-right National Front party is a strong contender to win the next French presidential election.

Meanwhile, France’s government debt has kept increasing every year since 2004 (although public spending has actually decreased) and stands currently at almost 95 percent of GDP at a time when the reduction of government debt in excess of 60 percent has been enshrined in the new Stability and Growth Pact, thus raising all kind of interesting questions about the future of fiscal policy in France, French politics in general, and of course, Franco-German relations. As hinted earlier, a deal may be reached between Germany and France over the latter’s budget, but there won’t be unity over growth.

What does the future hold for the eurozone?

Speaking of growth, it is simply remarkable that the euro zone’s GDP has failed to return even to its 2007 levels. Given that reality, calling the EMU a nonviable entity could hardly qualify as an exaggeration.

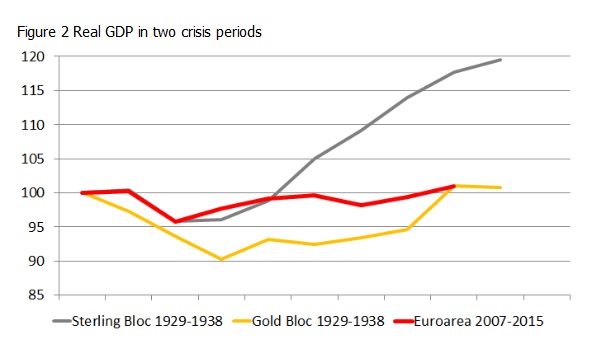

An interesting illustration of the inherently depressionary nature of the euro and the sheer failure of the current European monetary union comes across in the most pointed way when one compares the growth experience of the eurozone since the start of the global financial crisis of 2007-08 with that of the sterling bloc and the gold bloc countries after the Great Depression of 1929. As Nicholas Crafts, who undertook this comparison, notes, “the former [the sterling bloc] devalued in 1931 and experienced an early and quite rapid recovery. The latter [the gold bloc] stayed on the gold standard till the bitter end and even in 1938 had only just regained the 1929 level of real GDP. Sadly, the Euro area is following a trajectory that looks rather too reminiscent of that of the gold-bloc countries in the 1930s” (17) (see Figure 2 below).

In light of the above, the key question is: What does the future hold for the eurozone? The most obvious alternative for turning things around is a broad growth-based strategy across the euro area in a spirit similar to that of the New Deal along with specific policies that counter the internal imbalances in Euroland. However, the political and social support for such an undertaking is largely missing and the prospects of Europe moving toward a federal model are simply nonexistent. Thus, investing political capital in this project is probably a wasted and ill-conceived effort, given the sharp differences that exist in the political cultures of the 18 member states in the euro area and the fact that Germany has been the primary beneficiary of the current euro design, which means it is most unlikely to accommodate calls for a social Europe.

There seems to be a momentum growing lately in the direction of a euro exit.

A more realistic scenario for the future of the eurozone might be the creation of a two-tier euro system that separates the core member states from the peripheral eurozone countries. The outcome of this scenario will probably be dictated by political developments as much as by plain economics. Whatever the odds may be for this scenario to materialize, it is much more likely to happen than Germany surrendering to pressures to accept a fiscal union or euro zone debt mutualization options. Indeed, one should not be surprised to see at some point in the near future the emergence of a strategic alliance among a set of key countries for the purpose of forming their own euro currency.

The third and most unlikely scenario is the complete dissolution of the monetary union in Europe and the return to a mere single market, or a free-trade zone. It is a highly unlikely scenario by virtue of the fact that too many vested economic interests have made huge investments in the future of the euro.

The final and not so unlikely scenario entails some of the most highly indebted member states (Greece, Portugal, Spain and Italy in particular) leaving the euro. A widespread fear of a return to national currencies, greatly assisted by government and media propaganda throughout the periphery of the eurozone, has severely circumscribed public dialogue inside these countries, but there seems to be a momentum growing lately in the direction of a euro exit, especially in Italy, a political development that could have important contagion effects in the rest of the periphery.

In Greece, the likely rise of Syriza into power is unlikely to play a protagonistic role in the periphery of the eurozone, let alone become a catalyst of change in the entire euro area. Committed as it seems to be to maintaining Greece as a member of the monetary union, Syriza may ultimately find itself accepting European terms and conditions for Greece, which will prolong the nation’s status as a heavily indebted, underdeveloped and dependent nation indefinitely. But growing discontent in Italy with the euro regime, especially involving a decision to exit the eurozone, could indeed have major political ramifications in the rest of the periphery of the eurozone.

Meanwhile, pressures on the peripheral countries for more austerity and further structural reforms will continue as low inflation and marginal growth will sink them further and further into the depths of abyss, courtesy of the wildest experiment among modern monetary unions and of neo-Hooverian policies pursued by the eurozone’s hegemon.

Footnotes:

1. Data drawn from Eurostat statistics on general government gross debt – annual data.

2. The possibility of Marine Le Pen winning the next French presidential election could open up a Pandora’s box of more political shifts across Europe in a similar direction. See Hugh Carnegy, “Marine Le Pen takes poll lead in race for next French presidential election.” The Financial Times. July 31, 2014.

3. See Jose Ignacio Torreblanca and Mark Leonard, “The Continent-Wide Rise of Euroscepticism.” Memo Policy. London: European Council on Foreign Relations. May 2013.

4. Note that, unlike in the United States, where the crisis erupted with Wall’s Street’s crash of 1929, the crisis in England started in the early 1920s and Keynes – known in certain economic circles as the “master” – was already assisting the British government in developing public programs for combating unemployment.

5. See C. J. Polychroniou. “The New Rome: The EU and the Pillage of the Indebted Countries,” Policy Note 2013/5, Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. May 2013.

6. As an editorial in BloombergView has pointed out, “the bailout money . . . aimed to rescue German banks that had amassed claims of $704 billion on Greece, Ireland, Italy, Portugal and Spain, much more than the German banks’ aggregate capital.” See BloombergView, “Hey Germany: You Got a Bailout, Too.” May 23, 2012.

7. Alen Mattich, “Weaker German Industry Needn’t Be A Disaster.” The Wall Street Journal’s blog. August 21, 2014.

8. Ashifa Kassam, “Why a little economic growth won’t see an end to the pain in Spain.” The Observer. August 10, 2014.

9. Trading Economics, “Euro Area GDP Growth Revised Up.” October 17, 2014.

10. Graeme Wearden, “Eurozone growth grinds to a halt as German economy shrinks – as it happened.” The Guardian Business Blog. August 14, 2014

11. Angela Monaghan, “Germany needs ‘small miracle’ to avoid recession after exports fall by 5.8%.” The Guardian, October 9, 2014.

12. Eurostat news release euroindicators. October 14, 2014

13. Centre for European Economic Research. ZEW Indicator of Economic Sentiment – Further Economic Slowdown Expected. October 2014.

14. Ifo Business Climate Germany: Results of the Ifo Business Survey for September 2014. Press release. Ifo Institute. October 10, 2014.

15. Cited in Monaghan (2014), “Germany needs ‘small miracle’ to avoid recession after exports fall by 5.8%.”

16. William Horobin, “France’s Statistics Agency Cuts Economic Growth Forecast.” The Wall Street Journal Online. October 2, 2014.

17. Nicholas Crafts, “The Eurozone: If only it were the 1930s.” Vox. December 13, 2013.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $43,000 in the next 6 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.