The following is the introduction to Household Workers Unite: The Untold Story of African American Women Who Built a Movement:

“What matters in life is not what happens to you but what you remember and how you remember it.” – Gabriel García Márquez

In 2007 a landscape contractor in the exclusive New York City suburb of Muttontown, on Long Island, was sitting in his truck after purchasing a box of doughnuts when a malnourished, bedraggled woman approached him. Barely speaking English, the woman pointed frantically to her stomach and begged him to give her a doughnut. The woman, as was later learned through media accounts, was a household worker – one of two live-in Indonesian workers who had been virtually imprisoned and literally tortured by their employers for five years. They were beaten with rolling pins, scalded with boiling water, force-fed chili peppers, required to sleep on the floor in a closet, and only allowed to leave the house to take out the garbage. The employers – a wealthy married couple – were eventually brought to trial, convicted, fined, and sent to jail. This widely publicized case, an extreme but not isolated incident, rightly drew condemnation from many quarters and became emblematic of the vulnerability of private household workers: their isolation, their status as marginalized (and in this case noncitizen) workers, and the vastly unequal power relations that characterize the occupation.

Buried in the sensational news coverage was the fact that an organization of South Asian workers – Andolan – had learned of the case and begun to advocate on behalf of the workers. Andolan collaborated with Domestic Workers United (DWU) to organize a public demonstration in front of the courthouse as the trial took place. Founded in 2000 and composed of nannies, cleaners, and elder-care workers, DWU is a multiracial organization that adopted the slogan “Tell Dem Slavery Done!” Based in New York City, it holds rallies, organizes picket lines, lobbies legislators, and brings lawsuits on behalf of workers to improve labor conditions.

Andolan, DWU, and other organizations in this active and vocal household-workers movement are frequently overlooked in the media, while the victimization stories – like that of the Indonesian workers – dominate. Stories of domestic workers who need rescuing often appear in the popular press and circulate through the Internet. In short, the image of the disempowered and abused domestic worker is a common one, evoking pity and outrage.

The victimization theme plays out in the best-selling book and popular 2011 film The Help. Although the story is set in the turbulent decade of the 1960s, the workers profiled are not embroiled in the heroic efforts to overturn Jim Crow segregation or transform southern race relations. In fact, they need prodding and encouragement from the young white protagonist to speak out about their hardship. The story of The Help is one about black domestic life told from the perspective of a white employer and, in the end, reinforces dominant stereotypes of passive household workers. Rarely do we see such workers as agents of history. They exist on the sidelines, serve as a backdrop for the stories of others, or, when they are cast as the main actors, give voice to victimization and oppression. They remain nameless stereotypes, like the elderly black woman who, tired but determined, heroically walks to work rather than ride a segregated bus, or one of the thousands of African Americans filling church pews at a mass meeting in support of civil rights.

Although over one-third of employed black women in the United States labored as domestics in 1960, household workers are oddly invisible in histories of postwar social movements. Many Americans are familiar with iconic stories of political struggles, whether it is Rosa Parks’ refusal to relinquish her seat on a racially segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955, or the so-called bra burning at the Miss America Pageant in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in 1968, where women’s liberationists threw symbols of gendered oppression into a “freedom trash can.” These stories are often told in a particular way, with a clear political purpose: to illustrate the dignity in acts of civil disobedience as practiced during the early civil rights movement, in the case of the former; and in the latter, to demonstrate the women’s liberation movement’s opposition to women’s objectification. Preachers and students, sanitation workers and sharecroppers, are all given their due in such stories, but not domestic workers.

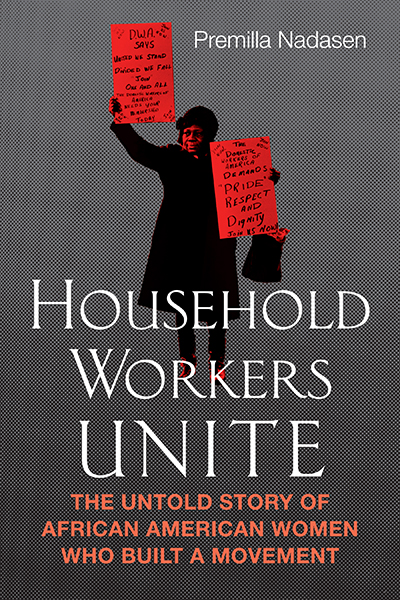

(Photo: Beacon Press) This book tells the story of household-worker activism from the 1950s to the 1970s, a pivotal period during which domestic workers established a national movement to transform the occupation. It is a story of women, primarily women of color, who have for the most part operated in the shadows of the formal labor movement, on the margins of the struggle for black freedom, and under the heels of the mainstream women’s movement. It challenges widespread assumptions about the passivity of domestic workers and paints a markedly different picture of household workers – one in which they do not need a savior. But it does more than that. It analyzes their strategies of mobilization and explores how storytelling was central to the way they organized and developed a political agenda. Household-worker activists shared stories that were passed down to them and told stories of their own experiences as workers. Their stories, which they connected to the struggle for black liberation, highlighted the racial exploitation of the labor and were part of a collective remembered history in the African American community. Storytelling was a form of activism, a strategic way to make sense of the past as well as the present and to overturn assumptions about domestic workers.

(Photo: Beacon Press) This book tells the story of household-worker activism from the 1950s to the 1970s, a pivotal period during which domestic workers established a national movement to transform the occupation. It is a story of women, primarily women of color, who have for the most part operated in the shadows of the formal labor movement, on the margins of the struggle for black freedom, and under the heels of the mainstream women’s movement. It challenges widespread assumptions about the passivity of domestic workers and paints a markedly different picture of household workers – one in which they do not need a savior. But it does more than that. It analyzes their strategies of mobilization and explores how storytelling was central to the way they organized and developed a political agenda. Household-worker activists shared stories that were passed down to them and told stories of their own experiences as workers. Their stories, which they connected to the struggle for black liberation, highlighted the racial exploitation of the labor and were part of a collective remembered history in the African American community. Storytelling was a form of activism, a strategic way to make sense of the past as well as the present and to overturn assumptions about domestic workers.

This book contributes to histories of labor and political organizing and makes a claim for how the voices and analytical perspective of working-class black women, as understood through their stories, can help us rethink the basic contours of the postwar period. Household Workers Unite is intended to intervene in the discipline – that is, offer a new way to think about how storytelling helps construct identities and how social movements create historical narratives and put them to use.

The stories recounted here are not stories told about domestic workers, but stories that domestic workers articulated themselves. The half-dozen African American women activists profiled in these pages were exceptional leaders and participants in a powerful social movement that sought to improve the lives of their fellow domestic workers. In the process of organizing, they shared stories of abuse and exploitation that drew on examples from history – especially the history of slavery and the notorious “slave markets” of the 1930s – to make their case for why they deserved rights. For them, slavery was a trope that connected past and present, illuminated power relations, and spoke to kin, community, and a legacy of racism. Consequently, invoking these stories served a political purpose: to mobilize other household workers and forge a collective political identity as workers. In the 1950s, the notion of an identity as a domestic worker – as opposed to domestic work simply being the work that one did – was not self-evident and had to be constructed. The movement eventually brought together twenty-five thousand women to fight for basic labor protections and transform relationships with their employers.

I begin in the mid-twentieth century, a critical moment in the history of domestic work, by tracing the powerful symbolic association of domestic labor with black women’s oppression, recounting the stirrings of a grassroots movement of domestic workers that evolved into a mass movement which fundamentally redefined black women’s relationship to the world of work. The occupation both reflects and ushers in dramatic changes in race relations. Domestic work, so representative of white racial oppression for the African American community, became an important platform for the politics of black liberation.

Organizing by domestic workers was distinctly different from other forms of labor organizing. As “invisible” work that took place in private households behind closed doors and was not always recognized as “real” work, household labor has been marginalized within the labor movement and, for many decades, was excluded from key labor laws. A central goal for domestic-worker organizers was to revalue social reproductive labor – paid and unpaid household work. Through their campaigns for respect and recognition of their work, they brought attention to labor in the home and expanded the definition of work that characterized much of the history of labor and labor organizing. This radical redefinition offered possibilities of alliance with feminists, since women, whether paid or not, were traditionally responsible for housework. But demands for higher wages also created tensions as greater numbers of middle-class women entered the paid labor force and increasingly hired household workers in order to pursue careers outside the home. In this case, their “freedom to work” led to further exploitation of private domestic workers.

There is a long history of individual, covert, day-to-day resistance among household workers. The women in this book, however, engaged in overt, collective, and public forms of opposition. They were vibrant middle-aged or elderly black women, very often mothers and grandmothers, who took multiple risks, made enormous personal sacrifices, and offered powerful critiques of the status quo. And it is in this context that the stories and crafting of an identity become important. Beginning in the 1960s, household workers organized forums, spoke publicly, circulated pamphlets, gave testimonials, and lobbied legislatures. Their political identity was bound up with the politics of race, gender, culture, and ethnicity, as their stories of the “mammy” image, the history of slavery, and patterns of servitude that shaped domestic labor illustrate.

Their class consciousness was also shaped through the inequality that characterized domestic work. The legal exclusions from labor rights such as minimum wage and workers’ compensation inform how and why an identity of “household workers” begins to develop in the postwar period. The broader cultural patterns and legal practices that degraded their labor led domestic workers to question whether employers should always be their primary target, and in some cases, they saw employers as potential allies. The intimacy of the work, where personal contact with employers was the hallmark of the occupation, also discouraged them from establishing an antagonistic relationship with their bosses. This form of worker consciousness, which didn’t necessarily make the employer-employee relationship the central contradiction, also distinguishes this movement from other forms of labor organizing.

Additionally, domestic workers advocated training programs, professionalization, fair wages, benefits, and model contracts. They formulated detailed and clearly defined work expectations and renamed themselves “household technicians.” Most of these women took pride in their occupation – in some cases organizing “Maids’ Honor Days” to bring respect and public recognition to their work. They wanted their work to be valued the same as all other work and they fought for the legal protections and collective bargaining rights to which other workers were entitled. Their political program included individual and collective empowerment strategies; they targeted both the households in which they worked and state policies that constrained them or devalued their labor.

The women domestic workers highlighted in this book claimed rights as workers. They drew attention to the home as a workspace, to the gendered labor of social reproduction, and to work that many claimed was invisible. Dorothy Bolden, Geraldine Roberts, Josephine Hulett, and others proved that domestic labor is not invisible, even if it is unrecognized. Unlike a factory worker who toils in a distant location that consumers rarely visit, domestic labor is hyper-visible, taking place in front of our eyes, every day. As such, the degradation of domestic labor is less about visibility than the way in which the work is perceived – as a labor of love – or the way in which workers are cast – as either “one of the family” or as less than human.

Because domestic workers were considered difficult to organize and neglected by most labor organizers, they had no choice but to strike out on their own. The African American women who led this movement in the 1970s utilized public spaces as centers of organizing, modeled alternative strategies of achieving worker power, and drew attention to the domestic sphere as a site of work. They reached out to immigrant and native-born workers, both the documented and the undocumented. Although they didn’t build the racially diverse movement they envisioned, they nevertheless had significant victories. While there were many previous efforts to reform and improve the circumstances of domestic workers, the movement of the 1970s was the first one to put the issue of domestic workers’ labor rights on the national political agenda.

Political identity is not given or fixed. It is forged through political struggle, through collective and individual stories, through narrative. The social world of domestic workers in this period was constructed through their words, stories, and silences. Although we don’t have access to every narrative, we do have access to some, which can help us understand the social reality of domestic labor for these particular individuals. This book is an attempt to piece together narratives of African American women in private household labor in the postwar period who came to develop the category of domestic workers as rights-bearing citizens engaged in socially and economically valuable work.

Since this struggle of the 1950s through 1970s, domestic workers’ representation in both the labor force and in the discourse of the labor movement has assumed enormous significance. In the past two decades, the dramatic rise in the number of household workers worldwide and several well-publicized instances of abuse and exploitation have drawn attention to the occupation. In response, another political movement of domestic workers has emerged under a different set of circumstances to insist on labor rights and occupational safeguards, claims that resonate with the movement of a half century ago.

In this new historical moment, the ranks of labor are under attack and union leaders grapple with how to move forward; capital increasingly treats workers as interchangeable or indispensable; the number of manufacturing jobs continues to dwindle and the number of service sector jobs expands; and a critical mass of workers in industrialized countries find themselves in precarious situations and struggle to make ends meet without state support or protection.

In this moment, the lessons of domestic-worker organizing might prove to be more important than just a correction of the historical record.

Copyright (2015) by Premilla Nadasen. Not to be reprinted without permission of the publisher, Beacon Press.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $29,000 in the next 36 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.