Once again I find myself among grieving families, among families who bleed and tremble when they speak, all the while insisting they are witnesses or survivors, not victims. All the families present at this United Voices Against State Sponsored Violence event have tragically lost family members to the scourge of law enforcement violence. And while the air is heavy with trauma here, there is also much strength at this standing-room-only event at the African American Community Service Center in San Jose, California.

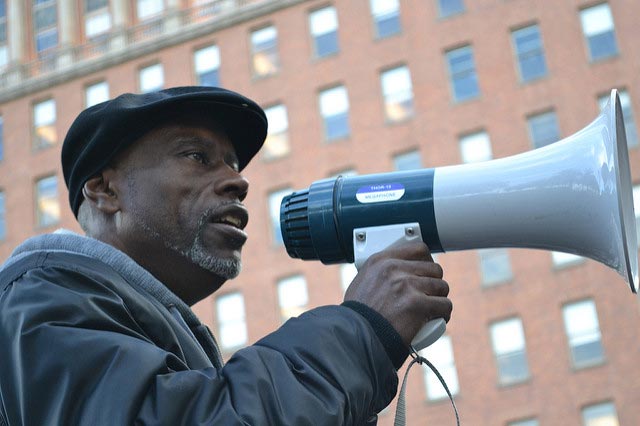

Family members are here to bear witness, affirming that they will not remain silent. “Silence is consent,” says Cephus Johnson, the MC of the event and uncle of Oscar Grant, who was killed by a Bay Area Rapid Transit police officer in Oakland in 2009. When a family loses someone to this kind of violence, many times, “they are shocked into silence. Sometimes they are just shocked,” says Johnson.

Other families represented here are those of Antonio Lopez Guzman, Richard “Harpo” Jacquez, Alex Nieto, Yanira Serrano, Diana Showman, Phillip Watkins, Rudy Cardenas and Steve Salinas, just to name a few. All of them were killed unjustifiably, and several of these cases are still mired in the criminal legal system.

Several years before, after a spate of law enforcement killings in Southern California, I attended an anti-police brutality rally in Anaheim, California, in the summer of 2013, where I noticed something similar. At this statewide multiracial rally, family member after family member (most of them Black or Brown) gave their testimonies regarding the killing of their loved ones and virtually everyone that spoke broke down while speaking. For some, that meant their voices quavered, whereas others had to be helped off the stage.

Whether one “wins” or “loses” in the courtroom, families and survivors are traumatized for life.

The previous time I had gone to something similar to this was in Washington, DC, shortly after September 11, 2001, for a gathering of survivors of torture and political violence. It was a powerful gathering: a time for survivors to speak and to protest the administration’s drive to legalize and normalize torture. They were offering themselves as evidence regarding the horrors of torture at a moment when the Bush administration was employing torture and justifying it as a necessary tool in the war on terror.

In Anaheim, I wondered if people whose families are tortured or brutalized or people who lose family members in other parts of the world due to state-sponsored violence suffer or grieve differently? I had the same thoughts in San Jose.

On this occasion in San Jose, I was there with other families as someone who has also experienced the wrath of extreme law enforcement violence in 1979 and the dehumanizing reality one lives in its aftermath (see my book Justice: A Question of Race). A reporter probably could have filed a story about the speakers and the content of what they said, but that would not have done justice to what transpired at this event.

How does one begin to put into words that which flows from broken hearts and shattered dreams? How does one explain the shock, the numbness, the pain, the anger, the loss of trust and even innocence … all the memories and emotions that come to the fore and that do not ever go away?

Angelica Garza, the sister of the late Frank Alvarado, spoke with so much anger that she made me feel that something was not right — but what would have felt right? Soft words and tears? She said, “I stand before you, but I don’t like it.” Her brother Frank Alvarado, from Salinas, California, was shot in 2014 by numerous high-velocity bullets while “armed” with a cell phone.

Another family member who helped organize the event was Laurie Valdez, the wife of Antonio Guzman Lopez, who was killed by San Jose State University police in 2014. As with all the families, she continues to press for answers. “The pain is forever,” she said, also explaining that their 5-year-old son, Josiah, is still waiting for his father to come home. Other times, “when asked by his friends about his father, he tells them, ‘The cops killed him because he spoke Mexican.'” This alludes to the fact that the Spanish-speaking Guzman Lopez was shot in the back, though university police maintain he charged at them with a 12-inch drywall knife. While both officers wore body cameras, the footage has not been released.

Sharon Watkins, mother of Phillip Watkins, who was killed by San Jose police in February 2015, also spoke of the nature of her pain. “Nobody needs to feel this pain because it cannot be healed,” she said. Her son, who suffered from depression and was reportedly suicidal, was killed by police. When the police arrived at the family’s home after a 911 call, Watkins had a knife, and two officers shot him. This is not an uncommon fate for those living with mental illnesses; law enforcement officers often kill people with mental illnesses rather than defusing situations that arise in law enforcement encounters.

Sometimes I feel uncomfortable seeing survivors or family members pour their hearts out because it involves a lot of retraumatization. I see survivors subject themselves to this all the time while recounting horrid details. While it can be healing, the reliving of trauma can also be very harmful, and yet people do this because they see it as part of a very special responsibility.

Sometimes I feel like I have learned everything there is to learn about this topic, and yet, during this trip, I made the realization that ending state-sponsored violence is about sacred justice. I came upon this concept accidentally. A close friend had scribbled a note regarding social justice on a police brutality scrapbook I have, though I misread it as “sacred justice,” just before speaking at the event in San Jose. At the event, I invoked the concept of “sacred justice,” a concept that I presented as something beyond the law, or more precisely, something beyond the criminal legal system.

As I spoke, something just poured out of me, drawing on my knowledge that many of us get ensnarled in the legal system, which in some cases becomes even more traumatizing than the events themselves. That is, the mainstream media often demonize and dehumanize those killed and it is ugly. This happens even if we win some kind of modicum of justice in the courtroom. But this idea of sacred justice has little to do with the law. Whether one “wins” or “loses” in the courtroom, families and survivors are traumatized for life. So what is sacred justice? Right now it doesn’t exist. And in the society we live in, it cannot necessarily exist. But I am convinced that is what we need to strive for.

I have monitored this extreme brutality for some 45 years. And I will say unequivocally that we do not currently have a system of justice in the United States. Some people would blame biased and unaccountable law enforcement agencies for this situation, and that would be correct. But more correctly, we need to understand that this lawlessness is also made possible by our biased criminal legal system, cowardly politicians and citizenry (biased juries).

This is not about a philosophical pondering about the origins and nature of this abuse and brutality. The fact that there have been virtually zero convictions of guilty officers over the past generation tells us that the only place to turn to is perhaps the international criminal courts — either the Organization of American States or the United Nations. Both criminal courts exist precisely for situations in which the courts in a given country do not function. And this is unquestionable when it comes to the brutalization of people of color in this country; the courts have never functioned. The issue of state-sponsored violence in this country is prima facie evidence that a reign of impunity for law enforcement has always existed, particularly when it relates to the abuse of the Black, Brown and Indigenous peoples of this country. Additionally, for these peoples, law enforcement has always functioned, more than anything, as a system of control.

Sacred justice would not simply involve a movement to compile cases like these and take them to either of these international criminal courts. Sacred justice would also include a responsibility to ensure that those brutalized or killed and their families, first and foremost, are never forgotten or neglected but honored. And it would involve a commitment to push forward into a future in which these near-unspeakable acts of violence will not happen again. It is all of these things, but truly, it is also beyond words — in this world of violence, we do not yet have the words to describe the essence of sacred justice.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $46,000 in the next 7 days. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.