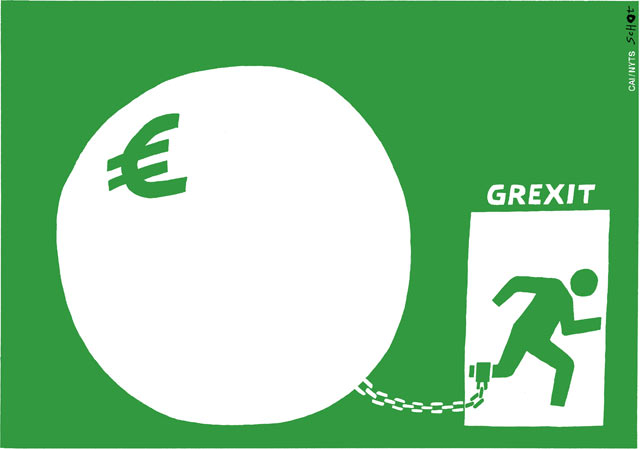

The Greek government has deployed a lot of populist and nationalist rhetoric lately, and eurocrats seem shocked. But the miracle is that this hasn’t happened until now.

A few years ago, debtor-country governments like Greece might have gone along with austerity programs in the real belief that they would pay off in the form of a strong economic recovery. But Brussels’s technocrats have lost all credibility on that front.

Furthermore, while center-right governments are in some cases managing to hold on politically by posing as the only people who can do the painful but necessary stuff, those center-left parties that have taken on the role of agents of austerity have imploded, and in some cases have essentially disappeared from the scene.

That said, individual politicians – center-right especially, but center-left in some cases – may do O.K. personally, even if their policies are wildly unpopular. They can become fixtures at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, or they can look forward to appointments at the European Commission or other European institutions. This has, I’d argue, acted as a deterrent to feeding the populist backlash that voters are ever more ready to endorse.

But the current Greek government isn’t center-left, and none of its leading figures are ever going to re-emerge as Davos men. For them, success must come in the form of support from their own voters rather than from international elites.

I’m not sure whether creditor governments understand this. Sometimes it seems as if they expect Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras to cave in any day now. Other times it seems as if their plan is to turn Greece into an object lesson in what happens when you don’t follow orders. There’s a lot of fuzzy-mindedness all around.

But this is getting dangerous.

A Note on Dollar Strength

The economist and blogger Tim Duy is having a debate with Scott Sumner lately, who insists that the strong dollar won’t hurt growth in the United States.

I think we need to think about this both conceptually and quantitatively, and I’m not nearly so sanguine.

Mr. Sumner, an economics professor at Bentley University, has written that you can’t reason from a price change: The dollar doesn’t just move for no reason, so you have to go back to the underlying cause and ask what effect it has.

Actually, asset price moves often have no clear cause – they’re bubbles, or driven by changes in long-term expectations, so you really do want to ask about the effects of price changes that you can’t explain very well. More specifically, Mr. Sumner is right when he says that if the euro’s recent fall is being driven by expansionary monetary policy, this affects the United States through the demand channel as well as competitiveness, so it may be a wash.

But I’ve already argued that monetary policy doesn’t entirely explain the euro’s drop in value. Instead, the currency’s fall seems to reflect the perception among investors that Europe is going to be depressed for a long time.

And if that’s what’s driving the weak euro and the strong dollar, it will hurt growth in the United States.

Join us in defending the truth before it’s too late

The future of independent journalism is uncertain, and the consequences of losing it are too grave to ignore. To ensure Truthout remains safe, strong, and free, we need to raise $31,000 in the next 48 hours. Every dollar raised goes directly toward the costs of producing news you can trust.

Please give what you can — because by supporting us with a tax-deductible donation, you’re not just preserving a source of news, you’re helping to safeguard what’s left of our democracy.